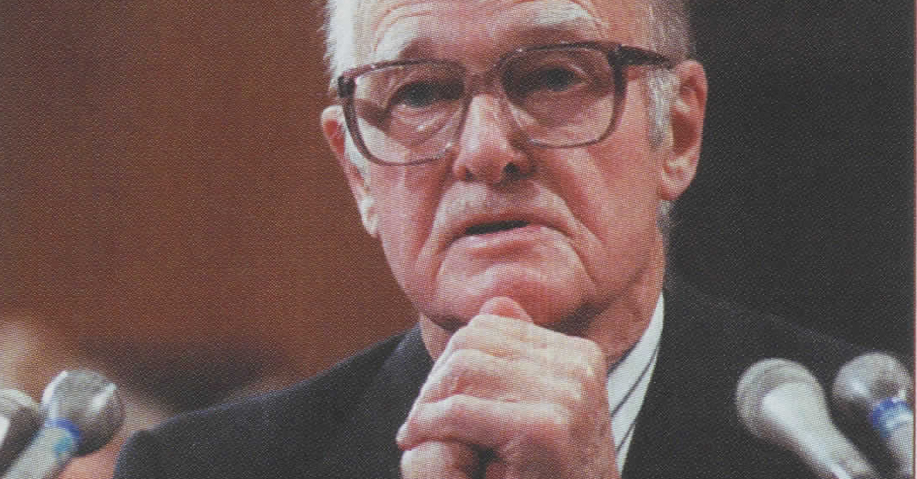

1904 – 2005

On March 17, the world lost one of the greatest diplomats of the 20th century, George Kennan, who died at the age of 101 at his New Jersey home. A descendant of Irish-Scotch settlers of the 18th century, Kennan was born in Milwaukee, February 16, 1904 and became one of the most influential men on American soil, shaping American diplomatic, political and military policies following World War II. He was also known as a prolific writer and historian with 17 books published, and countless articles. Recognition of his writings came in the form of two Pulitzer Prizes.

A graduate of Princeton, Kennan began his career in the State Department in 1926, and served as a Foreign Service officer until 1953. His first post was to Geneva, and he subsequently found himself assigned to posts in Germany and Estonia. He is now recognized as one of the great academic authorities on the Soviet Union. From 1931, he spent periods on assignment there, and had a great affection for the people and their culture, though he despised Communism. In 1952, he even spent a short time as U.S. Ambassador in Moscow, but this position ended abruptly when Stalin had him removed for saying that conditions in the Soviet Union were not unlike Nazi Germany. He briefly returned to his diplomatic background when during the Kennedy administration, he was appointed as Ambassador to Yugoslavia from 1961-1963.

His “reputation was made,” as he recalls in his Pulitzer Prize-winning memoirs, in 1946 when he sent a cable from Moscow to Washington which became known as “The Long Telegram.” The Long Telegram was a blueprint of what policies and approaches were necessary for Washington to competently deal with the Soviet Union. Ultimately, this blueprint became the actual U.S. foreign policy regarding the Soviet Union, until its breakup in 1991. Kennan had reiterated his views in 1947, coining the phrase “containment” in an article published in the Journal of Foreign Affairs, while he was chief of the State Departments planning staff. “It is clear that the main element of any U.S. policy toward the Soviet Union must be that of a long term, patient but finn and vigilant containment of Russian expansion tendencies,” Kennan wrote. He felt that there should be a military element to the policy, but that the policy should consist primarily of economic and political pressure.

Apart from his career in the State Department, he enjoyed an illustrious academic career as a diplomatic historian. Kennan won a Pulitzer Prize for history in 1956 for his book, Russia Leaves the War and again in 1967 for Memoirs, 1925-1950. Other book titles include, American Diplomacy 1900-1950, (1951) and Russia and the West Under Lenin and Stalin (1961). In the 1980s, he became an advocate for nuclear disarmament and believed that the threat of nuclear power was as effective as its actual use. He pleaded that there “is no one wise enough and strong enough to hold in his hands destructive power sufficient enough to put an end to civilized life on a great portion of our planet.”

Kennan is survived by his wife Annelise, four children, eight grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. ♦

Leave a Reply