Gerard McSorley was traveling the day a bomb shook the foundations of Omagh — his hometown. He was returning to Dublin, where he was living at the time, and his sister, who was in London struggling to piece together the events of the day, was frantic to reach him. On entering his house, he answered the phone to his sister’s hysterics. Images of bodies and general confusion filled her screen. The bomb detonated on Market Street in an area providing the economic needs for a population of no more than 17,300. The location was a mere 500 yards from the local courthouse and 200 yards from a bicycle shop once owned by Gerard’s father on nearby Bridge Street.

“I felt that my roots, my home, my mother’s garden, my father’s business, had been assailed by an incomprehensible barbarity,” he said.

On August 15, 1998, the day in question, McSorley tried to fathom the unfathomable, miles away from home.

“I switched on the television and watched the same pictures while talking to [my sister] on the phone, and I’ve never heard anyone weep so profusely,” he remembered. The bomb — planted by an IRA breakaway militia known as the Real IRA — killed 29 people, including four school children visiting from County Donegal.

“Both of us were catatonic with disbelief that such an atrocity had happened in a town that appeared to have no extreme sectarian divisions in the way that Belfast might have had historically. Omagh was never regarded as a dark, sectarian, or violent town, It’s just a market town which services the agricultural hinterland about.”

The following day, he returned to his childhood town and pulled into the Drumragh car park, where he was met with the silence of 10,000 of his neighbors holding vigil.

“There was no sound,” he recalled. “Even though there were maybe 10,000 people standing there, there was no sound expect for the sound of dogs and small children — that’s all you could hear.”

Though the bombing marked an especially tragic period in McSorley’s life (his sister was also dying of cancer at the time), and his account of the town’s communal shock leaves little room for laughter, his mood remained cheerful during the interview at the Tribeca Grand Hotel in downtown Manhattan. The location, less than 10 blocks from Ground Zero, makes for an eerie spot to discuss terrorism. McSorley recognized the irony.

“It was the same feeling of unreality that people would have had here,” he said, making a grand sweep of his arm.

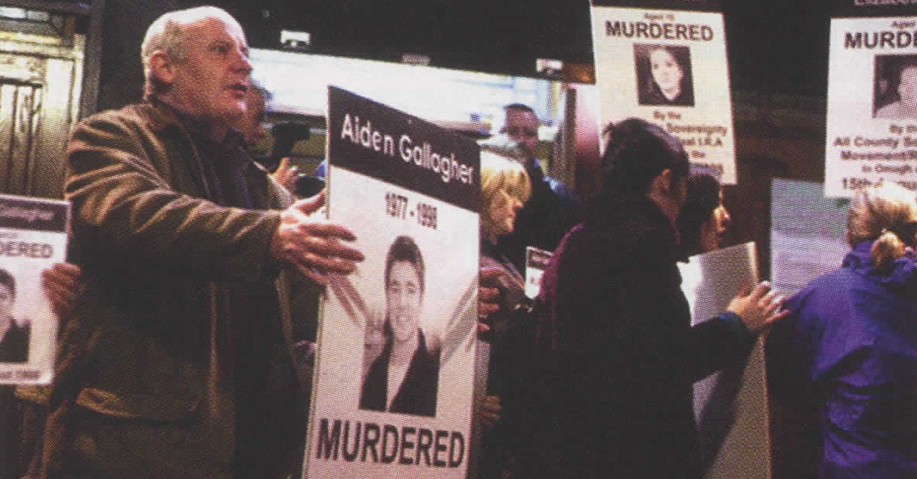

McSorley has had the opportunity to relive the event in his recent film, Omagh, which follows the tragedy through the eyes of Michael Gallagher, an ordinary citizen, a mechanic with a wife and two children, who loses his 21-year-old son, Aidan in the bombing. Weeks later, the traditionally soft-spoken man had become the key spokesperson for the Omagh Support and Help Group as they strive to find the truth of what happened that day.

The movie was made with the help of the support group and the Gallagher family who were consulted throughout the process. “There’s a beauty in Michael Gallagher the real man,” McSorley said. “There’s a beauty in his integrity, and I don’t mean this in a depreciative way, there’s a beauty in his simplicity and his directness. It’s a very Northern Ireland quality. He’s very straightforward, and absolutely never talks nonsense, I’ve never seen him do it, it doesn’t happen.”

As an Omagh native, McSorley felt especially accountable for his portrayal of Gallagher. In studying the man, McSorley recorded Gallagher’s voice, watched all his video appearances, even photographed the man’s shoes.

“Being involved in a movie that describes the biggest calamity in the last 30 years of Northern Ireland, especially as an Irish actor, is a big, big commission, and one that came with a tremendous responsibility.”

Those who are familiar with McSorley’s work would have no doubt that he was equal to the task. A veteran of some 40 films, he began his career on the stage working with Jim Sheridan at the Project Theatre in Dublin. In 1981 he joined the Abbey Players (he went on to star in Brian Friel’s Dancing at Lughnasa on Broadway), and the same year (1981) he made his film debut in Neil Jordan’s Danny Boy.

This coming year, McSorley will appear in the heartwarming sleeper Rory O’Shea Was Here and the new Ralph Fiennes drama, The Constant Gardener. But some of his best work, over the course of his career, has been in movies about Northern Ireland. He has appeared in Jim Sheridan’s In the Name of the Father (star-ring Daniel Day-Lewis as a man wrongly accused of an IRA bombing). And in Terry George’s Some Mother’s Son (based on the 1981 hunger strike), and Bloody Sunday (Paul Greengrass’s depiction of the 1972 civil rights march in Derry when British paratroopers shot and killed 13 civilians). Though it may seem that McSorley chooses films with a political bent, he swears that the script is the key.

“I find that film scripts that are sparse in dialogue are to me, the good ones,” he said before describing Greengrass’s script for Omagh as “a piece of music.”

Though the actor is extremely proud of his work in Omagh, for which he won an Irish Film and Television Award (IFTA), he seems the type of man not to allow anything, regardless of the honor, to overwhelm his innate good nature. He enjoys words (as is evident from his proclivity to use three in sequence when one will do fine), and he also likes a good laugh.

He’s happy to be in New York City for the premiere of Omagh at The Craic Irish Film Festival, and recalls with pleasure his time here in 1992 when Dancing at Lughnasa won a Tony for Best Play.

But honors are not where it’s at for this fine actor. Though he admits pride in his IFTA, which affirms the caliber of his performance, the honor is secondary to the approval of the families affected by the Omagh bombing, many of whom viewed a screening of the film two weeks before it appeared on Channel 4 in Ireland.

“They approved of it, liked it, and most of the families thought, to my delight, that my portrayal of Michael Gallagher was accurate enough, and that was payoff for me. Because that meant more than 1,000 words written by the most articulate film critic in the world.” ♦

Leave a Reply