“There were men and women, over their fences, shouting names and spitting and pulling people’s hair…and then a bomb flew over. Father Troy told us all to run. I thought everyone was going to die.”

Roisin Crawford was nine years of age during the infamous Holy Cross protest of 2001, when a group of Loyalist protesters, claiming provocation from local Republicans (including parents of the schoolchildren) as their motive, picketed Catholic schoolgirls on their way to and from school for 12 terrifying weeks. In a city where ownership of land is fiercely prized, particularly amongst the declining Protestant population, Holy Cross, servicing North Belfast’s Catholic Ardoyne community, has the misfortune to stand just inside Protestant `territory.’ Schoolgirls must walk through a stretch of road that belongs exclusively to the Protestant community in order to get to school.

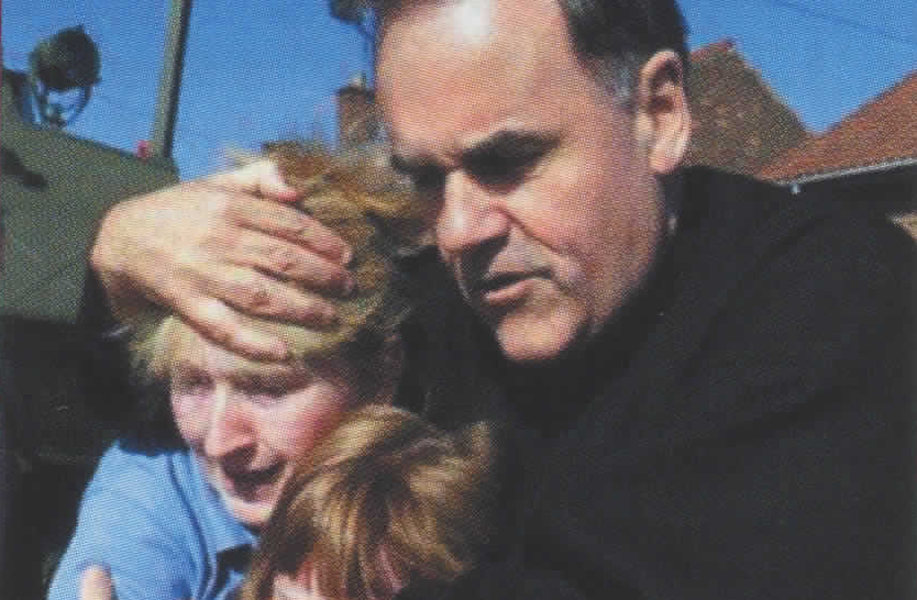

The pipe bomb that terrified Roisin Crawford that day was, thankfully, unique, but there was no shortage of other terrors. Each school day, children, some as young as four, their parents, and parish priest Father Aidan Troy had to endure spitting, urine bombs (urine-filled balloons), pornographic images, Halloween masks and abuse (cries of `slut’ and `whore’ were commonplace) hurled from faces contorted with hatred. The images of the schoolgirls, faces pinched with fear, clutching desperately to their parents as they hurried past the picket of screaming protesters, shocked a world seemingly anaesthetized to the horrors of Northern Ireland. Not even during the worst of the `Troubles’ had protesters directly targeted children.

There were many questions raised by the protest; few people, amidst the confusion, bitterness and anger of that time, appeared to have any clear answers. What kind of grievance could drive people to such prolonged cruelty against children? Why did the police not simply clear the protesters from the street? Why didn’t the parents just take another route to school to save their children this nightmare? Why was the protest allowed to go on for so long? It was to address questions like this that Belfast-based journalist Anne Cadwallader embarked on her definitive account of the episode, Holy Cross, the Untold Story, described by the doyen of Northern Irish political correspondents, David McKittrick, as `one of the most important books of the last three decades.’ Cadwallader has been reporting on Northern Irish politics for over 20 years for the BBC, RTE, Irish radio and newspapers, and her unique understanding of the people she writes about is evident throughout the book.

Beginning with the history of conflict in the notorious north Belfast flashpoint where Catholic Ardoyne meets Protestant Glenbryn, before detailing the unfolding drama of the 12-week protest, the book then looks at the actions of politicians, police, media and the clergy. Few emerge unscathed from this collective failure.

It is gripping but uncomfortable reading. As tensions are raised and the protest gets underway, the dilemma faced by parents and children is graphically portrayed. Marriages are placed under unbearable strain, parents divided as to whether to walk the normal or `alternative’ route, or whether to send their children to school at all. Traumatized children wet their beds at night, or are unable to sleep, terrified their homes will be attacked, fearful of what horror the next day will bring. Equally disturbing, Cadwallader finds no shortage of Loyalists to defend their actions. While the more politically astute among them quickly realized the damage the protest was doing to their cause, many others remain adamant to this day that they were right. They deny targeting the children and blame the parents for continuing to use that route, but feel they had no choice but to make a stand at what they insist was increasing Republican intimidation (though police statistics show a much greater degree of Loyalist attacks on Catholics) within the area and steady Catholic encroachment into Protestant areas.

Cadwallader thoroughly examines all the various arguments put forward. At the time of the protest much was made of the `alternative’ route, and the Holy Cross parents were often criticized for not taking it. In the book, we are taken along this route, 40 minutes a day longer for mothers with buggies and toddlers, walking along Loyalist streets, scrambling up muddy hills, over football pitches and through a hole in a fence to get into the back way into Holy Cross.

Most poignant is the chapter devoted to the children (the interviews were conducted by a counselor). Many had to be placed on medication to endure the protest, many still need counseling, and some clearly remain traumatized to this day, suffering terrible nightmares and anxiety attacks.

It is not all bleak. The figure of Father Troy, the priest who shepherded the parents and children each day of the protest, shines throughout the book. The strength and unity of the parents is extraordinary, and there are Protestant churchmen who battled against the odds to end the protest. And though, one week into the protest, the horror of September 11, 2001 diverted much of the world’s attention, strength can be drawn from the incredible support the parents and children received from people in the U.S. and other countries.

This remarkable book offers not only compelling account of the protest, it is also enlightening in its insights into the two communities that inhabit Northern Ireland’s sectarian divide.

`Holy Cross, the Untold Story’ by Anne Cadwallader.Published by Brehon Press, price (dollar equivalent of £10.99). To purchase in the U.S., visit the www.irishbooks.com website. ♦

Leave a Reply