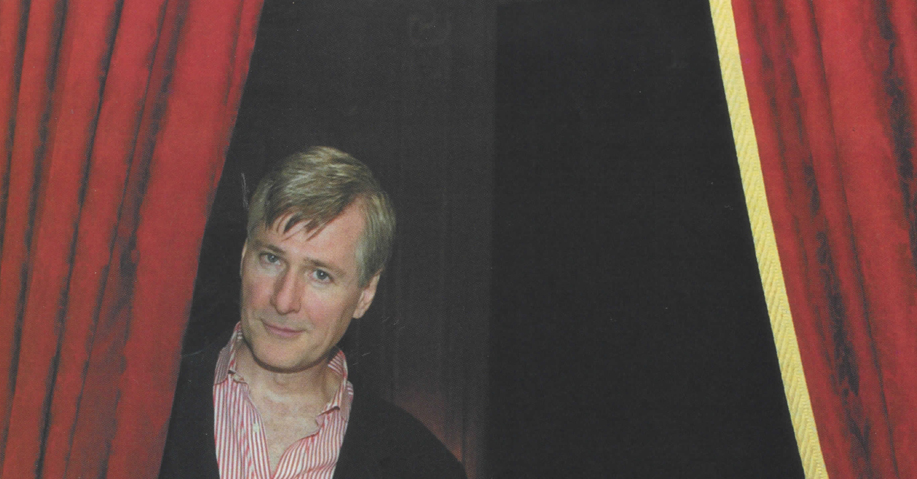

The current ubiquity of Oscar-winning playwright John Patrick Shanley in New York City’s theaters is unparalleled.

A brief walk around Manhattan finds his name in lights at three theaters, all for different productions of his award-winning dramas. A new play, Sailor’s Song, is at the Public Theater in the West Village, and he has two productions playing across from each other in Times Square. A revival of his hit Danny And The Deep Blue Sea is at the Second Stage Theater and the one we are discussing today, Doubt, is in previews at the Manhattan Theater Club.

It is an astonishing rise for an Irish-American born in the Bronx who had few artistic peers when he was growing up. In addition to his massive theatrical success, he has directed movies, written screen-plays and produced films. He delves into his past for much of his source materials.

Both of Shanley’s new plays are extremely close to his heart. Sailor’s Song was inspired by the unfortunate and untimely death of one of his beloved sisters. Doubt also comes directly from impactful events in his life.

Doubt is set in the 1960s in a Catholic school in the Bronx, where a nun becomes suspicious when a priest begins to take too much interest in the lives of his young male students. Shanley explains his family’s experience in this situation.

“A member of my family was abused by a priest. But that is not the only reason that I wrote the play; I’m not interested in writing a play that’s an exposé of a priest who is abusing children. You never know in the plot whether the priest did or he didn’t. That is one of the reasons that it’s called Doubt.

“Another reason it’s called Doubt is that it’s about the birth of the modern sensibility; the main character is the principal in the school, Sister Aloysius Beauvier. She lives in a clearly defined black and white world and then, out of the blue, she starts to be plagued with modern problems, today’s problems, and she has to deal with them. They leave her shaken, but more modern. And that to me is compelling.”

Doubt is set in an era when people, including the clergy, “were moving from a certainty about the way things should be into something quite different.”

This change began, Shanley explains, “When Pope John the 23rd called the Second Ecumenical Council in 1962 and representatives from all over the world came to Rome and talked about changes that needed to be made to the style of the Catholic Church.

“They changed the Mass from Latin into English, they became more community oriented. The priests who had been kept in place by dogma were told, `Hey, you can loosen up, and take the kids on a picnic.’ But with that loosening it did not necessarily follow that there would be an increased understanding of what it would mean to the individual celibate clergy person.”

It was when the template of dogma was removed that the church’s sexual scandals started happening, Shanley says. “They had lived in a state of denial and dogma — and they went haywire because they had never dealt with their own internal personality in its full extent.

“I am not saying there was no abuse before,” he hastens to add, “but there are statistics on when the abuse exploded. In terms of lawsuits there was specifically an eruption in the early sixties. And it continued but it was not so severe once this new aspect of the Church was fully digested by the clergy.”

Shanley, who has fond memories of the Sisters of Charity who taught him in elementary school, also says that the problems lay in the fact that the chain of command was entirely male. “It was a complete patriarchy,” he says. “The nuns answered to the priests. In some ways it’s almost Islamic. The women wearing black, and sequestered and living apart and, of course, virgins.

“The men in the Catholic Church ruled everything except the schools. They could not get enough priests to teach so they used nuns. So the church scandals broke first inside the church. Who found it out? The teachers found it out, the ones who were with the children in the classrooms and they were the nuns.”

He says that the stories you never hear about are the nuns who must have gone to the monsignor of the parish and said, `We have a problem. There is this priest who is chasing the boys and he is going to have to go.’ “There had to have been a lot of heroic, hard working, selfless women who protected these children, and agitated to get these rogue priests out. And that’s one of the main things my play is about.

“Of course,” Shanley continues, “the males in authority responded, not by throwing the offenders out of the priesthood, but by reassigning them and `rehabilitating’ them and covering for them.”

The blame for the cover-up reaches further than the church hierarchy, he says. “The media is the least of it. The police covered it up. The District Attorneys were covering for the Catholic Church, because they had a misguided respect for its authority.

“The priests are the way they are,” he adds sadly. “What I have a problem with is the people who covered up for them. I want to say to them, `You weren’t obsessed or out of your tree; you were just aiding and abetting a felony against a child.’ I still don’t understand why these people are not going to jail. Why aren’t the bishops and the cardinals in jail?”

As far as Shanley is concerned, the hierarchy has not shown enough remorse or been punished enough. “They should be in sackcloth and ashes doing public penance for what they allowed to happen in their own backyard. Why aren’t they saying, `We are the least among men,’ in true Christian humility? Instead they are behaving with their usual hubris, affecting a moral superiority that they have not earned.”

He can’t believe how the church hierarchy, “has the temerity to take a moral stance against [Senator] Kerry because of his stand on abortion, as if they have some kind of absolute moral authority.”

Shanley is still angry that the people in his family whose child was abused never got any satisfaction at the parish level. “They went to see Cardinal O’Connor, the most powerful Cardinal in America and he took them by the hand and said, `I am so sorry that this happened to you; I will take care of it.’ And he promoted the priest.”

While the incident is certainly something that Shanley draws on in Doubt, his creativity comes from “two fountainheads,” he explains. “The first is that I write plays from some event in my life, usually from quite long ago, and the images from such an event just sort of sit in some cellar of my subconscious year after year, aging like a Bordeaux. The other stream stems from the Zeitgeist, the spirit of the age.

“Back in World War II, we had a template of good versus evil that generated a rhetoric that mirrored the reality of that time. In the intervening years that rhetoric, that moral complicity, has continued to affect the national dialogue.”

That discourse is no longer appropriate, he says. “We live in a more complex society; our struggles are more complex, and they are often within ourselves. At the moment we live in a culture of debate and of advocacy so that people feel they can argue a position and they either win or lose. And doubt never seems to enter into it.”

Doubt undermines dogma, Shanley says. “Dogma provides a way of shutting down your mind. Dogma is anti-Socratic. Socrates had no interest in the doubtless quality that the faithful have, and the ancient Greeks finally put him to death for expressing endless doubt about everything.

“Doubt” he continues, “used to be the province of the wise, and has now been relegated as the province of the weak. Doubt is a sign of sophistication and strength, and contemporary TV shows like Crossfire, and phenomena like the presidential debates do not seem to allow for doubt. And I think that people would be relieved to hear leaders saying something like, `that is something that I really ponder about and I am struggling with.'”

Shanley, who has said that as a writer and a man, his one central straggle in life was to accept who he really was, was born in the Bronx. He and his four siblings were raised in a religious Catholic family. His mother, a Kelly, was first-generation Irish-American. His father was from a farm in Westmeath which still belongs to the family. “It was a very predictable Catholic household. We said the rosary every Friday night on our knees in the living room,” he recalls.

“I went to St. Anthony’s, a Catholic school in the Bronx. The Sisters of Charity taught us and they made a very big impression on me. And the priests made a very big impression on me in other ways.

“It was not an unpleasant time in my life,” he explains. “But things were going to get very bad for me right after that because in 1964 I was sent to the Irish Christian Brothers, and they were violent and they were bigots. And every time I looked at one of them it created a kind of instant nostalgia for the Sisters of Charity.”

Expelled from Cardinal Spellman High School, he joined the Marines Corps, and eventually went on to graduate as Valedictorian in his class at NYU.

He says that he thinks he had some genetic predisposition to be, not simply a writer, but a playwright. No one he ever knew, out of all the people he grew up with in the Bronx, went into the arts. But his father “had the gift of language so I was born with that.”

By the time he was eleven he had already started to write regularly, and though he had never actually seen a play being performed, he took his influence from television and the movies. The movies he liked best, such as The Devil’s Disciple, always turned out to be adaptations from plays. “I loved the dialogue, probably because it was stage dialogue.”

His play Danny and the Deep Blue Sea brought Shanley much critical acclaim when it was first staged in 1984. Now 54, he has been delighting audiences ever since with many more plays, including Four Dogs and a Bone, Psychopathia Sexualis, Where’s My Money? and Dirty Story, which explores the Israeli/Palestinian question, and played to rave reviews in the spring of 2003.

Shanley’s film career includes serving as writer, producer or director of films including Five Corners, Alive, Congo, and Joe Versus the Volcano. He won an Academy Award for his original screenplay for Moonstruck in 1987, which starred Cher and Nicolas Cage.

His creations are often spiked with a dark humor, acid wit, brutal honesty and razor sharp perception that leaves his audiences with a lingering, but satisfying, after-taste. And Shanley admits that he is sometimes affected by his own work.

Referring to Doubt, he says, “There is something incredibly tense and emotional about this play and in a way it has to do with my education, and my experience of what children need, which is complex. And there is no simple morality, no simple right and wrong to it. There is one scene in this play that makes even me cry and I don’t even know why.”

Shanley concludes the interview by comparing the experience of winning an Academy Award for Moonstruck with his present role as a down-to-earth playwright.

“It’s completely different. When I won the Oscar I wasn’t working. I was just receiving praise. Now I’m working. Receiving praise feels good like heroin feels good; you know there is going to be a big price to pay and you should be scared. Just working feels good in a good way. It’s really nice to work and do things that I really believe in.” ♦

Leave a Reply