“Eoin was never afraid to aim high. He played a seminal role in creating the transatlantic scholarly conversation that is Irish studies today, and he believed in his vision at a time when almost no one shared his dreams.” – James Rogers, Director, Center for Irish Studies, University of Saint Thomas.

℘℘℘

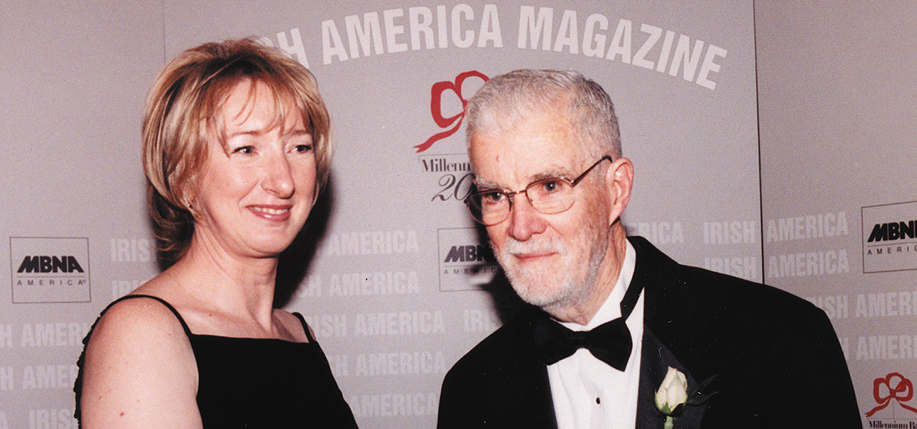

With the passing of Eoin McKiernan, 89, (see October / November 2004’s Last Word column) we reflect on his rich legacy that lay in his love of Ireland.

No one was more knowledgeable on Ireland or Irish America than Eoin. For many years – until the beginning of the year 2000 – he penned the Last Word column for this magazine. He wrote about politics and history, literature and language, of great events and everyday incidents that marked our passage. He told us stories of great heroes and reminded us of anniversaries such as that of Irish rebel John Devoy (September marking his birth and death), and brought to our attention those lesser-known champions that he admired. One such person was the linguist Jeremiah Curtin (the son of Irish immigrants and the first Wisconsinite to earn a degree from Harvard College), who he said “recognized language as the treasury, the transmitter, the myth maker and molder of societies.”

I was lucky to know Eoin as a mentor and a friend.

Increasingly, towards the end of his life, he began to see the Irish language as a vital component in the survival of our culture and he cautioned us to preserve it. “A smaller nation sharing a language with a much larger nation will dance to the tune of the larger one,” he wrote in his final magazine column (February / March 2000).

To Eoin, the Irish language (Gaeilge) was an essential part of our makeup. He must have been disappointed at the end of his life that Gaeilge is not recognized as an official language in the European Union. But he was surely cheered at the great debate its status has caused in Ireland.

The son of an Irish mother and a first-generation father, Eoin came early to the stories of Ireland. He especially loved County Clare, that place, rich in traditional music and song, from whence his mother came.

The immigrants of that era passed on the music and stories to their sons and daughters so that they might teach them to their children. In this way the land they loved, but were unlikely to see again, was kept alive in the hearts and minds of future generations. (I would have liked to have one last conversation with Eoin about my visit to Prince Edward Island [see travel piece “A Postcard from Prince Edward Island”] and its thriving traditional music scene, which was passed down in this way.)

Concerned that the oral tradition was being lost as Irish Americans assimilated, Eoin used the technology of the present to create dozens of public television programs celebrating Irish artists and history. In 1962 he founded the Irish Cultural Institute, and awarded grants to Irish writers, composers, artists, and Irish language endeavors.

And because he himself was profoundly moved by a trip to Ireland when he was 15 years old, he founded The Irish Way, a summer program for American high school students. By bringing them to Ireland and immersing them in its culture, he hoped to keep alive the flame in future generations. And he was successful.

Not only did his students learn about Ireland, they taught their parents and made return trips with their families. Today the Irish Cultural Institute is alive and well, as is the Irish Way Program. And when we look at Irish America, we see all the Irish Studies courses now being offered at universities and colleges across the states. And in all this Eoin McKiernan lives on – true pioneer and eternal flame. ♦

Leave a Reply