When I set out this year’s veggie garden, it never occurred to me that 6 eggplants, 5 peppers, 4 cucumbers, 6 string beans, 3 zucchini, and 8 tomato plants, plus a few 4-inch pots of herbs, would pose a problem. The seedlings looked so innocent sitting in the wide swaths of dirt recommended by my gardening manuals.

Four months later, the puny plants had morphed to monsters and I was swimming in produce. I cooked a non-stop parade of vegetarian dinners. When friends visited, they departed with bags of goodies. By mid-July, with the garden in full production mode, it was clear that I had two choices: wallow in guilt that I’d wasted even one cherry tomato or learn how to ‘can.’

The few times I’d witnessed a canning session had occurred decades prior when my mother, aunt, and grandmother pickled pecks of peppers. True. For days, the house reeked of vinegar. Like surgeons, they carved away every tiny blemish and sterilized every piece of equipment. But their tales of jams that never jelled and pickles that exploded left me loath to dabble in the arcane art.

But my kitchen table awash in vegetables called out for a solution. I couldn’t eat all my pretties, and I didn’t want to just give everything away. It was time to delve into the alchemical mystery of canning.

Knowing how to preserve part of the summer and fall harvest once meant the difference between life and death during the winter. The earliest method required nothing but summer itself. Long before hunter / gatherers created permanent communities, it was deduced that the sun’s mid-year heat would dry grains, fruits, vegetables, and even fish and meat. In many cases, the heat of a fire was just as effective and imparted a nice smoky flavor as well.

The next big advance came when it was realized that salting an item accelerated the process. That worked especially well with meat and fish, but vegetables tended to ooze liquid. This primitive pickling created something that tasted far different from its original form, but it wasn’t lethal and the item kept well for months. Honey is also a preservative, and fruits steeped in the golden stuff lasted as long as did the willpower not to consume the sticky treats. Both forms of preservation are mentioned in ancient food records, including Sumerian cuneiform, Egyptian hieroglyphics, Vedic scrolls, and the Bible.

Wine, or rather wine turned sour and transformed to vinegar, allowed for the next development in culinary preservation and was used in Greek and Roman times, as was the practice of submerging food in olive oil. Cane sugar was used widely by sub-Asian and Middle Eastern cultures, but it did not make any inroads into European cuisine until after the Crusades of the 10th and 11th centuries.

Credit for the final sophistication in food preservation – canning – goes to Napoleon Bonaparte. When the emperor decided to invade Russia, he offered a 12,000F reward to anyone who could devise a way to keep food from spoiling so he could feed his army on the long march. An ingenious candy maker, Nicholas Appert, solved the problem. He placed prepared food in heavy glass jars and submerged them in boiling water. The heat caused the contents to expand, forcing all the air out of the container. When the jars cooled, a sterile vacuum was created in which bacteria cannot grow. This is the same method that we use today.

Due to Ireland’s far northern latitude, an inhospitable environment for growing both grapes and olives, only monasteries and royal households were able to preserve food with vinegar or olive oil. Most food was put by for later consumption by the ancient methods of air or fire drying, or a brine made from water and salt collected from evaporated sea water. The latter process, called ‘coming,’ is familiar even now in one of Ireland’s most famous dishes: Corned Beef.

When it came to sweets, the Irish excelled. Honey, which played a key role in all ancient food preservation, was so valued that a special section of the Brehon Laws – the Bechbretha – is devoted exclusively to the regulations and practices of bee-keeping. Every three years, hive owners were obliged to distribute honey to neighbors from whose plants the bees gathered nectar. There were dictates ruling who should be allowed to eat honey (children of chieftains received as much as they could consume), how it should be collected, and even what should happen if someone was stung by a bee (the victim – rich or poor – was entitled to a full honey meal).

Making jam with honey is difficult due to the sticky stuff’s high water content, but that didn’t stop the Irish from satisfying their sweet teeth. Honey-based preserves have a more liquid consistency than sugar-based jams and jellies, but are equally delicious spread on a slice of warm soda bread, and have a long shelf life, thanks to honey’s natural antibacterial capability.

After the Normans arrived in Ireland, sugar began to appear on the tables of lordly manor houses toward the end of the 12th century in the form of costly sweetmeats. It was several centuries before the new sweet became available to the general population, but as Irish cooks gained access to sugar they quickly added the art of making jams, jellies, marmalades, and preserves to their culinary repertoire.

These delicacies were stored (especially in large manor houses) in a ‘stillroom,’ a special room that had few windows. Once the chamber that housed the home’s actual ‘still’ for concocting alcohol-based medicinals, the stillroom became the spot where preserved foods were prepared, and its floor-to-ceiling shelves, dim light and cool temperature provided a perfect storage environment.

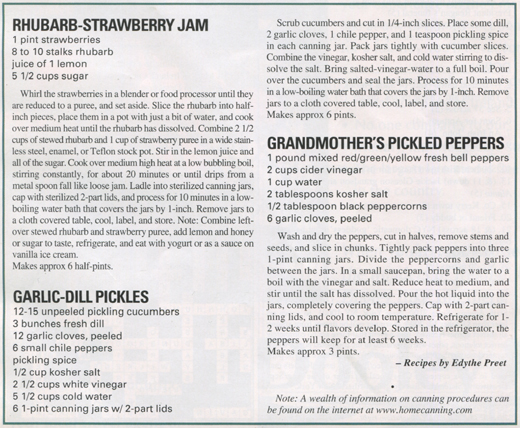

As the stacks of jars filled with colorful sparkling pickles, jams, jellies, and preserves grow steadily higher on my kitchen counter, I find myself wishing for a stillroom of my own. Though initially intimidated by the science of canning, it has proved to be simple although a tad time-consuming. Regardless, I am happily launched on a new hobby and hope that the following recipes will inspire you to do some experimenting so that you – and your lucky friends – can relish the tastes of the harvest when the winter winds blow. Sláinte! ♦

Leave a Reply