September 11 has become this generation’s “Day of Infamy.” The terrorist attacks forever changed the way we live, and have made our daily lives more difficult. A secure environment can no longer be presumed.

Some post 9/11 changes, however, have been positive. Is there anyone who doesn’t now have a greater appreciation for our police and firefighters, or greater respect for our armed forces?

Regardless of a person’s feelings about the war in Iraq, not since World War II has there been such a high level of support for our troops.

People recognize, more than ever, that the rights and freedoms we took for granted are at best fragile endowments. They could be shattered without a strong military to protect them. And the Irish contributions to that military tradition can only be described as remarkable. It has been extensive and is ongoing. Perhaps nowhere is this more clearly reflected than in the Congressional Medal of Honor, America’s highest military honor.

The medal, instituted during the Civil War, is issued sparingly. It can only be awarded to someone who has distinguished himself “at the risk of his life, above and beyond the call of duty.”

First issued in 1863, it coincided with the recent arrival of large numbers of Irish-Catholic immigrants. Many of them fled the Great Hunger in Ireland and some were destined to be among America’s first Medal of Honor recipients. But historians recognize that as far back as the Revolutionary War, independence from Britain would not have been possible without the contributions of those born in Ireland.

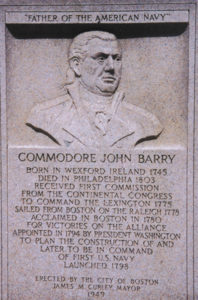

Commodore John Barry, an Irish immigrant from County Wexford, was designated by the United States Congress as the “Father of the United States Navy.” But in addition to Barry, George Washington’s Continental Army included many soldiers with Irish surnames such as Burke, Kelly, Murphy, O’Brien, O’Neill and Sullivan.

And historians credit Private Timothy Murphy with mortally wounding British General Simon Fraser. This helped lead to the surrender of British troops at Saratoga, which represented the turning point of the American Revolution.

Irish-born soldiers were such an integral part of his army that Washington even accepted membership in the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick. The Sons raised about one-third of the £300,000 it took to finance the war. This helped immeasurably to assure the young nation’s survival.

Washington held Ireland in the highest regard. “Ireland, thou Friend of my country in my country’s most friendless days,” he said. And, referring to the Irish accomplishments during the fight for independence, “who more brilliantly sustained it than Erin’s generous sons?”

Loyalist George Galloway, in testimony to the British House of Commons, described Washington’s Army as follows: “They were scarcely one fourth natives of America, about one half Irish, the other fourth English or Scotch.” Other estimates of the number of Irish have been even higher.

This explains Lord Mountjoy’s plaintive comment to the British Parliament after Lord Cornwallis’ surrender, that “England has lost America through the exertions of Irish immigrants.”

Notice that in Revolutionary times there were no references to the revisionist term “Scotch-Irish.” Participants in the war clearly distinguished between Scots and Irish. With absolutely no apology to the late, great novelist James Michener (a major proponent of the Scots-Irish misnomer), both England and George Washington considered these brave fighting men to be Irish.

It took courage and fortitude for both the huge number of Irish Protestants and the smaller number of Irish Catholics to join the Continental Army because a high percentage of the colonial population opposed the war. To defeat Britain, the world’s foremost power, was a long shot. And failure would mean possible execution for treason.

It staggers the imagination to speculate on the number of Medals of Honor which would have been issued to those Irish who fought in the Revolutionary War, had it been in existence then.

One surely would have gone to Edward Hand. Born in Ireland in 1744, Hand served as a doctor in the British Army until 1774 when he resigned to become a doctor in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. In 1775, he enlisted in the Continental Army and was present at the struggle for Boston in 1775 and for New York in 1776. He also fought against the British at Trenton and Princeton. In 1777, he was promoted to the rank of brigadier-general and became the commander of Fort Pitt.

The earliest military action to be recognized with a Medal of Honor was that of Irish-born Colonel Bernard Irwin of the United States Army. Although Irwin’s bravery occurred in the Indian Wars in 1861, before the Medal of Honor was instituted, he was awarded the nation’s highest military honor in 1894.

The list of Medal of Honor recipients – like so many of the best things about America – includes a cross section of every major ethnic group.

The fighting ability of the Irish, however, was held in such high regard that President Lincoln sent William Henry Seward, his Secretary of State, to Ireland to recruit soldiers for the Union Army. Seward was also the astute public official responsible for America’s 1867 purchase of Alaska from Russia for $7.2 million.

By any measurement, the Irish connection to America’s Medal of Honor is impressive.

At Medal of Honor Grove, Valley Forge, P.A., a monument in memory of foreign-born recipients of the medal is included on the site. It was dedicated by the Ancient Order of Hibernians in 1985.

A senior executive of the Freedoms Foundation gave me a personal tour of the 50 individual state groves. He also furnished me with a book, United States of America’s Congressional Medal of Honor Recipients and their Official Citations. The book has been updated through April 2001, and is the definitive source for information about recipients of the medal.

Interestingly, the official was surprised when he learned of the large number of recipients who were born in Ireland.

He is not alone. Although this subject has often been noted in the Irish-American press, I don’t recall any extensive coverage by the national media.

Research established that of 727 foreign born recipients, an astounding 255, or about 35 percent, were born in Ireland. This tiny country, whose current population is about half that of America’s largest city, has produced more medal winners than the next two countries combined.

One hundred and twenty five were born in Germany, and 94 in England. Some other countries represented are Canada (52), Scotland (35), France (17) and Italy (four).

Many Irish surnames occur among the English-born (Donnelly, Madden, Moriarty, Murphy, Sweeney) and Canadian-born (Cooney, Fitzpatrick, McCarthy, McMahon, Murphy, O’Connor, O’Neill). About half of the Canadian names appear to be Irish.

During the Civil War, 1,523 Medals of Honor were issued. A large number went to Irish troops such as those described by General Robert E. Lee. He characterized the efforts of the Irish Brigade at Fredericksburg thusly: “Never were men so brave. They ennobled their race by their splendid gallantry…”

The Irish Brigade also played a major role at Antietam, the bloodiest day in American history. More than 4,800 Union and Confederate soldiers were killed and 18,500 were wounded. The Irish Brigade lost 550 of its men.

Since the intention was that the Medal of Honor should be awarded only for the highest form of bravery, in 1916 Congress passed a law requiring that all past awards be investigated. In 1917, based on a review by five general officers, 910 names were stricken from the list.

The medal’s exclusiveness is illustrated by the fact that although 16 million troops served in World War II, only 463 medals were awarded.

It would be impossible, unfortunately, to calculate an exact number of Irish Americans on the Medal of Honor list. Suffice to say that Irish surnames are plentiful. The list includes 21 Murphys, 20 Kelly or Kelleys, and 8 Sullivans. And names beginning with the Irish pre-fix “Mc” spill over onto multiple pages.

In total, 3,456 medals have been awarded to only 3,437 recipients. The reason for the discrepancy in numbers is because 19 recipients won two medals each. Four of those multiple winners, John Cooper, John Lafferty, John King and Henry Hogan were born in Ireland. The other names include a Kelly, a McCloy, a Mullen and a Sweeney.

Statistics alone, of course, cannot tell a story. But a review of the accomplishments of a small sampling of recipients will help to put the achievements of all Medal of Honor winners in perspetive.

John King, from Ballinrobe, County Mayo, exhibited “extraordinary heroism” after a catastrophic boiler accident aboard the U.S.S. Vicksburg in 1901, and was awarded a Medal of Honor. In 1909, President William Howard Taft presented him with a second medal for the same action.

John Joseph Kelly received both the Army and Navy Medal of Honor. Born in 1898 in Chicago, Kelly, a private in the Marines, ran 100 yards in advance of the front line and attacked an enemy machine gun nest. He killed the gunner with a grenade, shot another member of the crew with his pistol, and returned through the barrage with eight prisoners.

One of the most fascinating figures in American history is William J. Donovan. A colonel in New York’s Fighting 69th during World War I, he suffered serious wounds as his men smashed through the elite troops of the Kaiser.

Donovan had been a star quarterback at Columbia University, where he earned the nickname “Wild Bill.” He was a classmate of Franklin D. Roosevelt, and he is widely regarded as the father of the modern American intelligence system. During World War II, he created the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) the predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

Winston Churchill credited Donovan and William Stephenson, a Canadian, with “the single outstanding intelligence coup of World War II.”

With the German Army blitzing down the Danube, Donovan flew into the Balkans where the Yugoslavian government of Prince Paul had caved in to the Germans. He arranged an overthrow of the government by the Yugoslav Air Chief, causing Hitler to rush in three Panzer divisions, tying up the Germans for five weeks. This forced the Germans into the fatal Russian winter, which proved a major turning point in the war.

Donovan died on February 8, 1959.

Audie Murphy earned his Medal of Honor during World War II and became that war’s most decorated hero.

Murphy was raised in poverty in Texas. He dropped out of school in the fifth grade to help support his mother and eight siblings, after his father abandoned the family. When his mother died, the younger children were placed in an orphanage.

After being turned down for service by the Marines and Navy, Murphy was accepted by the Army in June 1942. He stood 5′ 5″ and weighed 112 pounds.

At boot camp, Murphy passed out during training and the Army tried to make him a cook. He refused. Later, he turned down a post-exchange clerk’s job. He went on to fight in nine major campaigns and was wounded three times.

On January 26, 1945, Murphy stood atop a burning tank destroyer and, though wounded, single-handedly held off six German tanks. By war’s end, according to some estimates, he had killed more than 250 enemy soldiers and was still believed to be only 19 years old, having lied about his age to enter the army.

After Murphy’s discharge, another Irishman, actor Jimmy Cagney, invited him to Hollywood and he became a movie star. He suffered serious post-traumatic stress during his adult life, and died, ironically, in a Memorial Day weekend plane crash in 1971, near Roanoke, Virginia.

Fr. Joseph Timothy O’Callahan, not only the first Catholic chaplain to receive the Medal of Honor, but the first chaplain of any faith to be so recognized, was awarded the medal for action on March 19, 1945.

And for his gallant leadership and fighting spirit, O’Hare Airport in Chicago, was named for Lieutenant Commander Edward H. “Butch” O’Hare, a World War II fighter pilot hero.

O’Hare’s medal was awarded posthumously for his courage in saving the U.S.S. Lexington from enemy fire. On February 20, 1942, the Lexington was approximately 400 miles from its destination of Rabaul Harbor in the Solomon Islands when O’Hare and another pilot picked up the formation of enemy fighters closing in. Within moments, O’Hare’s wingman’s guns jammed, and without assistance, he fought off attacking twin-engined heavy-bombers; making the most of his limited ammunition, he shot down five planes and severely damaged a sixth. His citation described his action as “one of the most daring, if not the most daring, single action in the history of combat aviation.”

In 1943, at age 29, O’Hare failed to return from a mission, and was declared dead in 1944. Although O’Hare was from St. Louis, the publisher of the Chicago Tribune led the drive to rename the Chicago-area airport (formerly named Orchard Field) in O’Hare’s honor in 1949.

Another well-known facility, McGuire Air Force Base in New Jersey, is named after Medal of Honor recipient Thomas B. McGuire.

McGuire, also a World War II ace, shot down 38 enemy planes. This represented the second highest number for any pilot during that war. Two months before he was scheduled to return home, his plane stalled and he was killed while flying over the Philippines on January 7, 1945. His last act involved trying to help a fellow fighter pilot in trouble. McGuire was awarded his Medal of Honor posthumously.

Roger Hugh Donlon was one of the Vietnam War’s first Medal of Honor recipients. As a Special Forces Commanding Officer, on July 6, 1964, he defended a military installation against a fierce enemy attack lasting five hours. He detected an enemy demolition team of three near the main gate and quickly annihilated them. After sustaining a severe stomach wound, he was also wounded in his shoulder as he pulled a fallen comrade out of a gunpit. He then carried a mortar weapon to a new location, where he discovered three wounded defenders and administered first aid to them. While dragging much-needed ammunition to his men, he was hit by a hand grenade and suffered a leg wound. While moving from position to position, Captain Donlon, though seriously wounded, hurled hand grenades and inspired his men to superhuman effort. A mortar shell then exploded, again wounding him, this time in the face and body. When daylight arrived, the enemy had retreated to the jungle, leaving behind 54 dead and many weapons.

Donlon grew up in Saugerties, New York, the eighth of Paul and Marion Donlon’s 10 children. His father was a WWI veteran. All four of his brothers served; one was wounded in action.

Six months after the attack, still recovering from his wounds, Donlon became the first Green Beret in history, and the first American soldier of the Vietnam War, to receive his nation’s highest honor.

Another early Medal of Honor recipient from the Vietnam War is New York Irish American Robert Emmet O’Malley. In August, 1965 as a U.S. Marine, he led his squad in an assault against a strongly entrenched enemy force. While under fire and in great danger, O’Malley raced across a rice paddy to reach the Viet Cong, single-handedly killing eight of the enemy. Although wounded three times, he continued to press forward and assist other units, firing his rifle into the enemy with telling effect.

In all 245 men were awarded Medals of Honor for action in the Vietnam War. Included in this number are Major Patrick Henry Brady, Major Kern Dunagan, Captain Robert F. Foley, Lieutenant Commander Thomas G. Kelley, Spc. Thomas McMahon, Lance Corporal Thomas Noonan, Private Daniel Shea, and Petty Officer Michael Thornton.

There have been millions of Irish and Irish Americans who have served in our military with distinction. The latest is Col. James Hickey, who led the mission to capture Saddam Hussein. Hickey, the son of Irish immigrants, a Chicago native and commander of the 1st Brigade of the 4th Infantry Division, is representative of the Irish who continue to serve with distinction in the U.S. Armed Forces today.

Clearly, the Irish achievements in the military have been extraordinary. And the number of Medal of Honor recipients born in Ireland is astonishing. But don’t expect to read about them in a supplement to the New York Times Magazine, or view a three-part PBS miniseries about them, for they still remain a chapter in America’s forgotten history. ♦

Leave a Reply