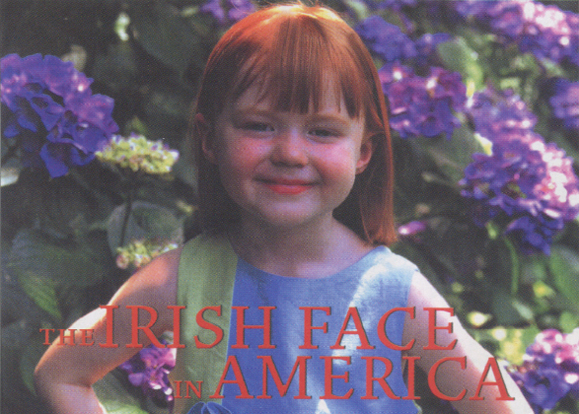

The Irish Face in America, a stunning book of photographs and text, by writer Julia McNamara and photographer Jim Smith, delves beneath the surface to show us who we are today. Here is the introduction by Pete Hamill.

℘℘℘

Of one thing I’m certain: there is no such thing as an Irish face, yet I know one when I see one. In physiognomy, Seamus Heaney does not resemble James Joyce, and neither looks like Flann O’Brien. All three are triumphantly Irish. So are all the people in this wonderful book. Their faces tell us, in some mysterious way, that they are all part of the same tribe.

For decades now, anthropologists have explained to us that the ancient Celts were small, dark-haired people. Yet there are many tall Irish people with red hair and blue eyes, and Irish people with mops of curly black hair, and others who are bald at 23. Some have dour, angular, unforgiving faces, while others seem formed by a state of permanent mirth. There are hawk-nosed Irishmen and pug-nosed Irish women. There are some with features as blunt as axes and others with features as refined as a Gainsborough. On a trip through Dublin or Cork or Belfast, or among the Irish of the various diasporas, there are Irish faces that are open and welcoming, and faces that are frozen into closed urban masks.

The variety of the faces reflects the island’s long-tangled history. Look hard and you can imagine the Norsemen arriving each winter for warmth and pillage. For them, in flight from Scandinavian wind and ice, Ireland was a kind of Miami. You can see Normans and Anglo-Saxons roaming the Irish countryside, looking for targets of sexual opportunity. Centuries of colonists left certain faces behind, full of self-righteousness, of moral doubt, and, occasionally, of guilt. You can see the legendary sons of Andalusia cast upon Irish shores by the storm that sank the Armada, all those Castillos turned into Costellos. You can see the Spanish sailors who traded in Galway Bay and were driven by love to stay behind. You can see the abrupt features of German settlers in the 20th-century South and of straying GIs in the North. There are as many different Irish faces as there are ways to be Irish. Ireland, like most countries, is plural.

In America, the Irish helped form the human alloy of cities, starting in the unhappy years of the 19th century. In my own New York, many Irish immigrants settled into the vile slum called the Five Points, which they shared with African Americans and small number of impoverished Germans and Jews. The ghettos of the time were based on class, not race or religion:; Harlem was a phenomenon of the early 20th century. And so some Irishwomen married the sons of slaves. Some Irishmen married women whose parents spoke Ashanti or Yoruba. Most worked their way out of the Five Points. Some of those who stayed behind were savaged by racist Irish louts during the Draft Riots of 1864, usually for the crime of loving someone from a different branch of the Irish tree. The best of them endured. So did their names – I’ve known three different black Americans named Kelly.. And so did the Irishness in the faces of their children and their children’s children: a certain amusement in their eyes, an Irish grin, a simmering Irish anger. You can see fragments of that Irish-African past today, on faces from New York to San Francisco and many places in between, including the American South. They should remind us (although the history is seldom mentioned anymore) that in the years before the American Revolution, the indentured Irish and the manacled Africans were sold together in the same British slave markets of Charleston and Wall Street.

But there were many other mergers among the strangers in a strange land. Irishmen and women married Jews or Germans or Italians. They found love with Puerto Ricans and Cubans and Mexicans. In the years of racist anti-Asian immigration laws, when there were few Chinese women in New York or San Francisco, a number of Chinese men found Irish wives. Their children were beautiful. Such mergers were not general, but there were enough of them to show that some of the Irish, when they had forever left the Old Country behind, were comfortable with people who were not like them.

That was certainly true of life in the Old Country too. Those who were not like them were generally of the same race, if such a category has validity anymore. But there were barriers between the Irish themselves that seemed insurmountable: class and religion. Yet even those barriers often fell. In the North, where the quarrels of the 17th century persisted, some friendships between Catholics and Protestant endured, even after the terrible years that followed 1968. Here and there, a Catholic married a Protestant, knowing that such a union could risk each partner’s life.In the darkest of those years, I had people in Belfast or Derry tell me that they could distinguish a Catholic from a Protestant by the look of a face.

In the United States, religion was less important than class when judging Irish Americans. John O’Hara was a tough, prickly Irish-American writer, too easily offended, but in his 1935 novel, Butterfield 8, he touched on the Irish face as a kind of evidence, like a flag. His autobiographical character, Jim Malloy, cranky and hard-drinking, takes a well-off young American woman to a speakeasy. As they look around, the subject turns to class. The woman, Isabel Stannard, protests his touchiness:

“I beg your pardon, but why are you talking about you people, you people, your kind of people, people like you. You belong to a country club, you went to good schools and your people at least had money–”

“I want to tell you something about myself that will help to explain a lot of things about me. You might as well hear it now. First of all, I am a Mick. I wear Brooks Brothers clothes and I don’t eat salad with a spoon and I probably could play five-goal polo in two years, but I am a Mick. Still a Mick. Now it’s taken me a little time to find this out, but I have at last discovered that there are not two kinds of Irishmen. There’s only one kind. I’ve studied enough pictures and know enough Irishmen personally to find that out.”

“What do you mean, studied enough pictures?”

“I mean this., I’ve looked at dozens of pictures of the best Irish families at the Dublin Horse Show and places like that, and I’ve put my finger over their clothes and pretended I was looking a Knights of Columbus picnic – and by God you can’t tell the difference.”

“Well, why should you? They’re all Irish.”

“And that’s exactly my point…”

A bit later he adds: “I’m pretty God damn American, and therefore my brothers and sisters are, and yet we’re not American. We’re Micks, we’re non-assimilable, we Micks.”

Such talk now seems part of the distant past. Irish America has had its president. It has its captains of industry. It has more than its share of writers and journalists, acclaimed lawyers, honored professors, and scientists. Sports and entertainment were once the way out of the Irish-American ghetto, as they continue to be for African Americans. But there are no longer any Irish prizefighters, nor Stage Irishmen. In the National Basketball Association, there are far more Irish-American coaches than Irish-American players. The enduring O’Hara-like touchiness and defensiveness that I saw when I was young are almost completely erased. Gone too is the belief among many Irish Americans that the deck is stacked against them simply because of their Irishness. I have lived long enough to see Irish America win all the late rounds.

Perhaps that’s why these Irish faces have a new aspect to them, one that was seldom seen half a century ago. There is pride in many of the faces, but little vanity. There is the knowledge of what it takes to overcome adversity. There is a relaxed quality to many of them, the ease that comes from knowing that you are getting the most you can possibly get out of the only life you will ever live. There’s also, in the eyes, a sense of irony. That sense is always based upon an understanding of the difference between what is said and what is done, what is promised and what is delivered. The Irish in America, like the Irish in Ireland, have paid all the dues necessary for such knowledge. There is no such thing as an Irish face, but I know one when I see one. ♦

_______________

Reprinted with permission of Bulfinch Publishers.

Leave a Reply