The unique Irish / Scottish heritage of PEI, off the coast of Nova Scotia, is preserved in music and dance and in the faces of the people.

℘℘℘

“An always but never known place” is how Australian writer Thomas Keneally described his first visit to Ireland. That about describes how I felt a few hours after landing on Prince Edward Island (PEI), Canada’s smallest province (about 120 miles from tip to tip), off the coast of Nova Scotia.

Deep-green potato fields and quiet clay roads make up the heart of the island, and embrace the little villages and lovely coastal inlets with red-sand beaches. And with about three-quarters of the population descended from Irish or Scottish settlers, there is also a definite Gaelic consciousness.

The opening of the Confederation Bridge connecting the island to the mainland seven years ago has brought increased tourism, but fears that the pastoral countryside would change with the influx have gone largely unfounded. Before the day-trippers, and the golfers (PEI has 26 golf courses) and the wind surfers, many of the visitors to PEI came here because of a red-haired orphan girl whose fame has reached far and wide, and includes a large following in Japan.

Anne of Green Gables, the turn-of-the-last-century fable, was also a much-loved book of my own childhood, and so a visit to Green Gables farm, set in Cavendish County, is my first stop.

Built in the 1800s, the house, once the home of cousins of author Lucy Maud Montgomery, portrays the Victorian setting described in the novel, while the outbuildings, a display of farming artifacts and accompanying photo exhibition, provide a glimpse into the life of the early settlers on the island. A picture of children picking potatoes, for instance, sparks a flashback to my own childhood in Ireland when country kids such as myself also participated in this backbreaking task.

PEI is Canada’s main producer of potatoes. There’s even a museum dedicated to the humble tuber in the township of O’Leary on the western shore of the island. Also worth a visit whilst in western PEI is the Heritage and Cultural Centre in Tignish. Settled in 1799 by eight Acadian families and joined in 1811 by two Irish families, the community, with a population of 833 citizens, retains its French / Irish influence and has since become a successful fishing community.

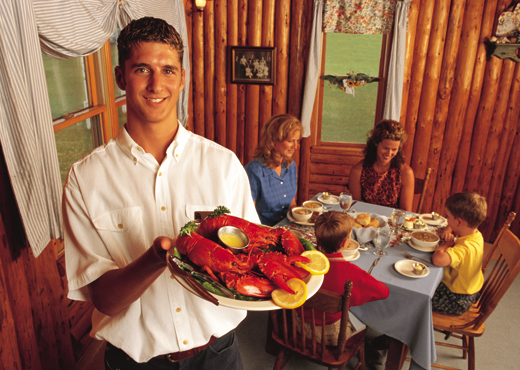

Fishing is an important part of the island economy, and helped the islanders survive during hard times. During the Depression lobsters were so plentiful that children used to take lobster sandwiches to school – they became know as the poor man’s sandwich. And so, a Lobster Supper is a must, not least of all because it is sure to be accompanied by Irish music. “We play it continuous,” the manager of Fisherman’s Wharf assures me as I tuck into my very large lobster and equally large baked potato to the sound of The Clancy Brothers.

PEI is noted for its rich fund of musical talent. There’s a thriving traditional music scene, with weekly ceilidhs and concerts where Scottish and Acadian fiddlers are just as often seen on the stage as Irish. And if the bagpipe is more your style, the College of Piping hosts summer-long evening concerts with performances featuring piping, drumming and Highland dancing.

Festivals abound throughout the summer and fall as heritage and local produce are celebrated. A stop at Mount Stewart Heritage River Festival, finds a crowd of onlookers gathered on the bridge, where, perhaps in honor of the festival, a school of dolphins has made its way up river.

Mount Stewart is truly a beautiful spot. The edges of the Hillsborough River are fringed with marsh grasses and trees of majestic birch, beech, and maple. You can rent a bike at the Trailside Inn for a pleasant ride along the river trail, which is what I did.

Later, back at the Trailside, I devour a succulent lobster roll – poor man’s sandwich indeed – and decide a relaxing swim is what’s called for. A woman at the cafe points me in the direction of Savage Harbor and I get the feeling from the look she receives from her husband that she has let me in on a local secret.

Not the best at following directions anyway, I drive over dirt roads, make several wrong turns, retrace my tracks, and finally, at the end of a dirt road that I thought was leading nowhere, is the most beautiful red-sand beach I have ever seen. It is absolutely deserted – not a human or dwelling or sign of modern life in sight. I can hear grasshoppers, and see white butterflies and driftwood and tall grasses and shoals of birds. The water is alive with sea things, living shells, and clear and cool in the mid-afternoon heat.

Savage Harbor, like everything else on PEI, is pristine. The natives, too, have a quiet air of calm and order. Lots of churches but no pubs, except for the few in Charlottetown; drinking is done in clubs. Any differences that in Northern Ireland have caused problems between Scots Protestants and Irish Catholics are handled with politeness and deference, or so it seems.

Ties to Ireland and Scotland are strong. At the Barachois Inn, a splendid Victorian country house, in Rustico, Andrea MacDonald is in charge as her mother and grandmother left just that day for Ireland. Andrea’s speech has the lilt and fall of a Donegal accent, and not for the first time in my visit am I surprised by how Irish people here sound. Andrea’s great-grandfather emigrated from Donegal, and when he had saved up the money he sent for his wife and six children. His son Patrick died on the voyage, Andrea tells me: her own tow-haired son, also named Patrick, hanging about her legs.

The Farmers’ Bank of Rustico, dedicated to the history of the other group of settlers on the island – the Acadians – is right across the road from the inn. I soon learn how closely Acadian history parallels our own.

Teresa Gallant, who acts both as custodian and tour guide, is a soft-spoken woman who quietly tells of the expulsions under the British. The period from 1755-1762 was the worst. The Acadians (French) in Nova Scotia were stripped of all their rights and placed on overcrowded vessels for places unknown. Following the fall of Fortress Louisbourg (1758), 3,500 Acadians were deported from l’Île Saint-Jean (as PEI was then known) to France. Seven hundred of these perished when two ships were lost at sea.

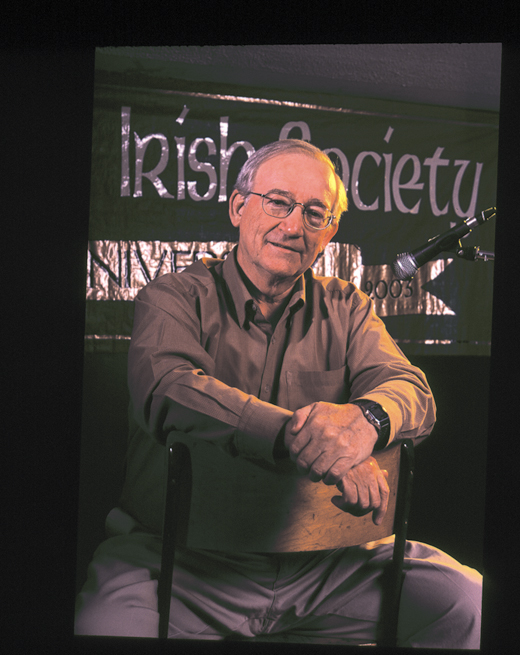

The tumultuous story of the Acadian makes me anxious to learn more of PEI’s Irish heritage, and George O’Connor of the Benevolent Irish Society picks up the story over lunch at Dalvay by the Sea, a Tudor fantasy next to Tracadie Bay.

“I’ll tell you now,” says George, who is well-versed in the history of the island, and soon fills me in on how the Irish settlement came to be.

After the Treaty of Pads in 1763, the entire island was transferred to “deserving” English men – divided into 67 lots of approximately 20,000 acres each, distributed in lottery system. Each new proprietor in return for the land grant agreed to settle his lot with 100 Protestants within 10 years.

Only a few titleholders tried to settle their lots, some sold them off, which is perhaps how Captain John MacDonald of Glenalladale, Scotland, came to own lots 35 and 36. From 1770 to 1775 MacDonald brought over several hundred Scottish Highlanders who established farmsteads around both sites of Tracadie Bay. Contrary to the prescriptions of ownership, these settlers were Roman Catholic.

MacDonald also played a part in one of the large Irish settlements. The captain’s son was a Catholic priest in Glasgow and through his contacts with a priest in County Monaghan, in 1830, some 800 Monaghan settlers arrived on the island. Throughout the 30s and 40s thousands of other Irish would follow, seeking relief from poverty and famine in Ireland.

Owen Connolly was one of those immigrants. Born in 1820 in the town of Donagh, County Monaghan, Connolly came to PEI in 1839 at the age of 19. He began life on the island as a farm laborer but ended up as one of the most important entrepreneurs on the island. By the 1870s he had a network of stores, owned his own bank, and was a major exporter. But he never forgot his poor beginnings. He left a large portion of his estate “for the purpose of educating poor children resident in Prince Edward Island, who are Irish, or the sons of Irish fathers.”

Dr. Brendan O’Grady, who has published a book on the Irish on PEI, continues the story over dinner at The Claddagh. A New Yorker whose father was from Tipperary, Dr. O’Grady recently retired from St. Dunstun’s College (now renamed the University of PEI) where the program for implementing Connolly’s fund was established. Over the years he saw the benefits of Connolly’s largesse, which as well as benefiting students who otherwise would not have had the opportunity for such an education, helped the college through tough times.

The Claddagh, a handsomely restored historic building on a side street in Olde Charlottetown, is owned by Liam Dolan, one of the few modern-day immigrants on the island. From Galway, Liam’s been on the island since 1979. He came over initially to help out his brother Tony, who had been working as a chef until he broke his neck diving into a wave.

The tragedy helped unite the Irish on PEI, revitalizing the Benevolent Irish Society. Founded in 1825, the society had been down on membership through lack of interest. Today, Tony is well, and the BIS is involving itself in cultural endeavors.

There’s a concert / ceilidh in the Benevolent Irish Society Hall tonight, and after dinner Dr. Grady volunteers to show me the way to the hall, pointing out Connolly’s house as we walk past.

The concert is in full swing when I get there. A woman from Ontario requests “Kevin Barry,” a song about an Irish rebel who was hanged by the British, and Ed Fitzgerald, the singer, who has never been to Ireland but knows all the songs, does a good job of it. Ed, whose grandfather was from Ireland, is the last of 10 children brought up on the island. He and his wife Ruth sing several more songs, to the delight of the audience, mostly tourists from the mainland, including “I’m a Working Man,” a song by Newfoundlander Rita MacNeil.

George O’Connor takes to the stage next and sings an island song, “When Johnny Went Ploughing for Kieran.” And then it’s time for some fiddle music, perhaps the best I’ve ever heard, from islander Roy Johnstone, just back from the Isle of Skye.

David Corrigan is manager of the hall and he and his wife run the ceilidh concerts, ably assisted by the Conboys, a couple from St. Paul, Minnesota, who lead the lesson in set dancing. I’m persuaded to take the floor for the “Waves of Tory,” which is sort of a Northern Ireland version of the Siege of Ennis. It starts off gently enough but then speeds up until I’m flying off my feet. It takes several cups of tea before I’m revived enough to make my way back to the Inns on St. George, convinced that Irish culture is alive and well in this corner of the world and can do without my further participation.

Located in the heart of Charlottetown’s Historic District, the Inns are a unique cluster of three tastefully restored, 1800s properties, whose owners are Paul Smith and Mike Murphy.

Mike’s mother is an O’Keefe whose family is from Wexford. Paul’s family came over with that 1830’s wave from Monaghan. Both are attentive hosts, making sure that everyone is enjoying their stay. And with a nod to their Irish heritage, the complimentary breakfast is served as “A Woman’s Heart” plays over the sound system.

Dr. O’Grady had talked about the Irish Settlers Memorial, and so after breakfast I pay a visit to the harbor. Dedicated in 2002, the memorial has a Celtic Cross and 32 stones laid in the ground, for 32 counties and also to symbolize the 32 meridians and the Irish around the globe.

The rock from Monaghan faces the open sea, and I can imagine the 800 immigrants arriving on the island in 1830, not knowing what fate awaited them.

Later that day I drive through the Kinkora / Shamrock area, surrounded on all sides by lush green potato fields. I think those early settlers must have felt at home in this lovely, fertile spot.

Settled by Irish immigrants back in 1834, Kinkora remains a predominately Irish community today. It is here, “the agricultural heart of P.E.I.,” that most of the potatoes are grown.

The scenic heritage roads in this region are a treat to drive. Unpaved, they are red clay, and mostly empty except for the occasional car, which sends up a cloud of dust. But then, every inch of this island has something unique to offer.

On my last day I wind my way slowly up the coastline to the northern tip, stopping at various villages, including St. Peter’s where I learn about the various stages of settlement in the community. Several archaeological digs have found traces left by the major cultures that have existed on PEI, including early aboriginal peoples, the Mi’kmaq, as well as the Irish, Scottish, and French settlers.

Further along the road, Greenwich, located on a peninsula that separates St. Peter’s Bay from the Gulf of St. Lawrence, offers self-guiding interpretive trails over wetlands and various natural habitats in which numerous rare plant species are found. The landscape varies from secluded wooded areas to open spaces, and the trails end up in a magnificent sand dune overlooking a spectacular beach.

It’s dusk when I stop in at Monticello Hall, a log cabin, where a ceilidh is in progress. The crowd mainly seemed to be locals. The fiddler plays “Rosin the Bow,” a tune I recognize, and the music is a powerful pull. As has happened in the past few days, I see faces that remind me of home, and once again I’m caught up in something that’s akin to awe at the indestructible aspects of our culture. The music and dance have survived wars and famine and brutal colonization, to unite all us Irish who wander the globe, providing both the essence of who we are and a link to the ancients.

I dance one or two dances and listen to the music. It is late when I take my leave. The Johnston Inn is warm and welcoming. A full moon hangs over my bedroom window and I can barely make out the cliffs below.

The next morning I take a stroll along those cliffs and gingerly make my way down to the rocky shoreline that is reminiscent of Ireland’s Berra Peninsula. The rocks are slippery and make walking difficult but it’s so completely remote as to make you feel completely alone on the edge of the earth.

Geologists claim that Ireland was once part of this North American landmass, and I can believe it. Though I’ve never been here before, it seems a place I’ve always known.

_______________

Prince Edward Island Travel Guide

ATTRACTIONS:

Green Gables, the farm that inspired the setting for L.M. Montgomery’s novel.

The Farmer’s Bank of Rustico Museum / (Hours 10:00 am-5:00 pm.)

The Gallery at The Dunes. Fine crafts by 70 contributing artists.

Walk the magnificent sand dune system at Greenwich, and visit Saint Peter’s.

Catch a ceilidh at Benevolent Irish Society Hall / (902-892-2367), or the Monticello Log Hall / (902-628-1254)

Try a walking tour of Historic Charlottetown with the Confederation Players, and see the Irish Monument.

Wander the streets of Victoria-by-the-Sea. The charming village is home to many artists and PEI’s smallest lighthouse.

Drive the Kinkora / Shamrock area, and scenic heritage roads in the region.

DINE:

Lunch at Trailside Inn Café & Adventure. (Rent a bicycle here and bike the Confederation Trail.)

The Claddagh Room. Live music upstairs at the Olde Dublin Pub / (902-892-9661).

Fisherman’s Wharf Lobster Suppers / (1-877-289-1010)

Dalvay by the Sea, dining and accommodations / www.dalvaybythesea.com

ACCOMMODATIONS:

The Barachois Inn. Innkeepers Gary and Judy McDonald / (902-963-2194) / www.barachoisinn.com

The Johnson Shore Inn / (1-877-510-9669) / https://www.jsipei.com/

For more information about Prince Edward Island, call 1-800-463-4734 or visit https://www.tourismpei.com/ ♦

Leave a Reply