Say what you will about Ronald Reagan, but it can’t be denied that he changed the face not of just American politics, but Irish-American politics.

Since the time of the Famine, when shrewd political bosses such as New York’s Boss Tweed saw votes in the desperate millions as they stepped off of coffin ships, Irish-Americans were loyally tied to the Democratic party in the U.S.

The list of big city mayors (as well as the lucrative patronage jobs they controlled) from the 1880s on reads like an Ancient Order of the Hibernians membership list.

When an Irish Catholic finally ran for president (Al Smith in 1928), it was no surprise he was the product of a Democratic machine.

Some Irish-Americans (including Al Smith) didn’t care for President Franklin Roosevelt, elected in 1932. But the vast majority of Irish voters looked to FDR to help the U.S. out of the Depression, and later World War II.

And yes, it is also true that some Irish didn’t care for JFK (more Harvard than Irish, some felt). Many more saw in him glamorous proof that the Irish had finally arrived in America.

But things began to change as the 1960s spun out of control. Stunning numbers of Irish-American voters abandoned the Democratic party in 1968, voting for Richard Nixon, or even George Wallace.

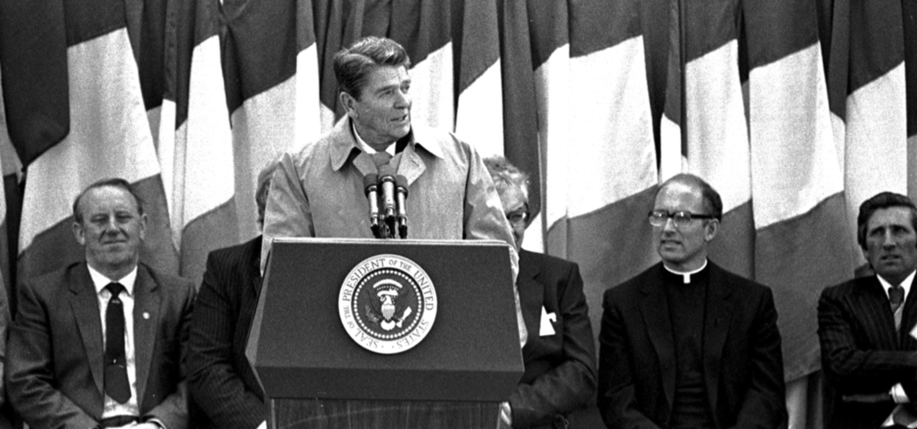

The transformation of the American political scene was not complete, however, until the 1980 election. And Ronald Reagan, as well as Irish-American Catholics, played a huge role in that transformation.

People disagree seriously when it comes to Ronald Reagan, regarding both his personality and policies. Although there are many fair criticisms of Reagan to be made, his electoral victories in 1980 and 1984 were resounding ones.

Among the most important voters were the so-called “Reagan Democrats.” Typically, Reagan Democrats were depicted as mid-Western factory workers who were hit hard by the economic downturn in the 1970s.

But Irish-Americans were key “Reagan Democrats” as well.

Why? In some ways it was a perfect storm of factors that led many Irish-Americans to vote Republican for the first time in their lives in 1980. By this time most Irish voters had left the ethnic enclaves and moved to the suburbs of New York, Philadelphia, Chicago and even notoriously liberal Boston.

The Democrats had helped the Irish weather the storm of the Great Depression in the 1930s, and to come into some prosperity by the late 1960s. Yet the well-documented instability of the 1960s and 1970s was shocking to many Irish-Americans. Reagan tapped into that with his call for renewed American optimism and a belief that America could be a proud leader on the world stage once again.

Go ahead. Smirk at such sentiments. It was the mistake Reagan’s critics always made. He simply went ahead and won heavily Irish-American states such as New York in both 1980 and 1984.

It’s not so surprising that Reagan was popular with Irish voters. If the Irish had become more conservative, it’s because they finally had something to conserve.

Meanwhile, the cornerstone of Reagan’s presidency, in many ways, was a strong stance against communism, an issue which always resonated deeply with Irish Catholic voters. So deeply, in fact, that while this wrinkle is often forgotten, during the election of 1960, many historians believe it was JFK, rather than Nixon, who excessively exploited fear of Communism.

It also could not have hurt that Reagan had an Irish name, even if his roots in Ireland, though strong, are also a bit tangled. Reagan’s parents were a mixed-religious couple, so one child was baptized into the Church, while Reagan was not, depriving him of one of the most easily identifiable aspects of an Irish-American upbringing. Meanwhile, unlike New York’s Al Smith or Boston’s JFK, Reagan did not hail from a famous Irish stronghold and was associated mostly with the glitz and glamour of sunny California.

Nevertheless, Reagan once and for all severed many of the durable Irish ties to the Democratic Party. Some feel that the Irish abandoned the Democratic Party, but others feel it was the Democrats who abandoned the Irish.

In 1996, journalist and author Samuel G. Freedman discovered that the Irish were such a big part of the Reagan Democrat movement that he based a large chunk of his important book on this fact, and titled it The Inheritance: How Three Families Moved from Roosevelt to Reagan and Beyond. In the book, Freedman looked at three generations of the Irish-American Carey family, who prayed at the altar of FDR in the 1930s, yet by 1980 believed Ronald Reagan was the right man for the right time.

Among those interviewed by Freedman was Tim Carey. Appropriately, Carey is a top official with the Battery Parks City Authority in New York and a close ally of New York Governor George Pataki. Among Carey’s most notable accomplishments was helping to plan, build and open the poignant, much-praised Great Hunger memorial in downtown Manhattan, marking the early political history of Irish-Americans.

_______________

Tom Deignan is a contributing writer to Irish America and The Irish Voice newspaper. His acclaimed book, Coming to America: Irish Americans, was published in 2003 by Barron’s. ♦

Leave a Reply