Ten years after robbers emptied an armored security van of $7.4 million at gunpoint, a former I.R.A. member has admitted in a memoir that he masterminded the heist.

℘℘℘

Sam Millar rues the fact that he is unlikely to set foot in New York ever again. He spent 16 years in the city, saw his four children born there, set up a successful comic book business in Queens and blew it all by leading a two-man raid on the Brinks facility in upstate Rochester. The 1993 robbery bagged about $7 million — $5 million of which was never recovered — but in one of the highest profile cases of the decade, Millar was belatedly nabbed by the FBI and sentenced to five years in jail.

In keeping with the rubrics of his extraordinary life, he had served 16 months of incarceration when outgoing President Bill Clinton signed an extradition order allowing Millar to complete his sentence at Magilligan Prison, Co. Derry. It was one of Clinton’s last acts as U.S. President and it secured a commitment from the Belfast man that he would never return to the U.S. And so another remarkable chapter closed, redirecting Sam Millar onwards, destination, as ever, unknown.

“I think about New York every day,” he says without hesitation. “I miss it so much. I know I brought it on myself and it was my own fault but sometimes it feels like a bigger prison sentence not being able to go back. I regret doing what I did against the Americans because they were so good to me.

“I didn’t like America. I loved it. My kids are all American. It was the first country I tasted freedom, but there was a recklessness in me at the time. If I had got away with it and Brinks came up again, I would have done it again.”

Carrying off a $7-million heist in what was considered an impregnable fortress might be enough action for most lifetimes. However, at 49 years of age, Millar time already divides into three sections, each of which teems with moments of sacrifice, drama and joy. These thoughts occur to me as I wait to meet him for the first time in the New Lodge Road, a nationalist enclave spliced between loyalist Tiger Bay and the Shankill Road in North Belfast. Each high-rise block in the New Lodge bears a mural in memory of an IRA hunger striker who died in 1981.

This is where it all began. Or where it begins to make sense.

I see a bespectacled figure approach in the distance. Wearing a denim jacket, he’s fairly stocky, his brown-gray hair tight on the sides and combed back on top. He raises his hand in recognition and we meet halfway, our first contact made beneath a giant mural of Bobby Sands while a British Army helicopter whirrs overhead.

Millar was on the blanket protest in Long Kesh when coded tapping on prison water pipes told him Sands was dead. And the grim messages kept coming to his cell until a deal was finally reached to bring the IRA hunger strike to an end. It was 23 years ago, but even in times of relative calm, past and present juggle for attention. Millar’s neighborhood, for instance, previously served as a barracks for British Army personnel. His own house was used as a residence by a British Army colonel. “Ironic, aye?” he shrugs, swinging open the front gate.

His introduction to Long Kesh began years earlier when he was 16. Millar was the first to be tried by a non-jury Diplock court, and he was sentenced to three years for membership in the IRA. The day he was released from prison he reported back for active duty. Within 11 months he was back in the Kesh on a 10-year sentence for carrying explosives. Along with other republican prisoners, he took on the prison authorities, demanding political status and rebelling against mistreatment. Millar was one of the first men on the blanket (see notes) and, characteristically, also the last. “It may have been 20 years ago but it was only yesterday,” he feels. “Being a blanket man is an experience you never forget.”

We’re in his kitchen and Sam — named after his grandfather, an Orangeman — is making coffee. A sheaf of handwritten notes rests on the table beside a laptop computer. Writing has become Sam Millar’s elixir, and his memoir On The Brinks topped the best-seller list in Northern Ireland.

As he relates in the book, his family background is working class of mixed religion. Politics aside, he was raised by his father after his mother absconded. It was a traumatic time. “There was such a stigma about your mother leaving home that we’d just say she was sick upstairs,” he recalls wryly. “We kept that going for years. The Guinness Book of Records: Sickest Woman in the World.”

His childhood sweetheart Bernadette — “I fell in love with her the first minute we met” — lived close by in loyalist Tiger Bay. Living on either side of the sectarian divide presented its own danger, but events detonated elsewhere. By chance he was in Derry on January 30, 1972, and witnessed Bloody Sunday (see notes), a key episode in a catalogue of experiences that drove him into armed republicanism.

“You’d have to have lived in Belfast in 1969-70 to understand what it’s like to be oppressed,” he begins. “I wasn’t brought up to be a slave. There was no sectarianism in my family — I have cousins in Tiger Bay. Some are UVF, some are not UVF, just like here where there’s IRA and not IRA. All working class. A lot of it is survivalism.

“I have no regret for it. If I hadn’t taken that route, someone else would have had to do it. I couldn’t accept being treated as a second-class citizen, and I wouldn’t want it to happen to Protestants either. Nobody deserves to be treated like that.”

The blanket protest lasted nearly eight years. On his release in 1983 it was time to get away, to America, where the second installment of Sam Millar’s remarkable life began. To sympathizers, he was a veteran of the nationalist struggle, a man who could not be broken by the British penal system. With their help, he got a job in the underground casinos of New York, working his way up from croupier to manager. He married Bernadette and they built a comfortable home. Living in Queens, they raised three daughters and suffered the heartbreak of losing a fourth, Roxanne, to medical complications. Deeply loved, she has not been forgotten.

“I had a reputation,” Millar realizes, putting down to “myth” the regard with which he was held in some American-Irish circles. A tough guy. Not someone to mess around with. An ex-cop friend (Tom O’Connor) worked at the Brinks Security in Rochester. One day O’Connor showed him around the facility and Millar absorbed it all. “It was an opportunity so ridiculous I couldn’t let it go,” he recalls. “I was making nice money in the casinos, but it was there laughing at me. I took it as a challenge.”

Finally, the Belfast man teamed up with an American-Italian in 1993 and they robbed the Rochester facility at gunpoint. Though no shots were fired, the possibility of a shootout still needles him. “It has been on my head,” he admits. “I can only say thank God it didn’t happen. Nobody got hurt and nobody got caught. It was a perfect crime.” He pauses. “But it wasn’t.”

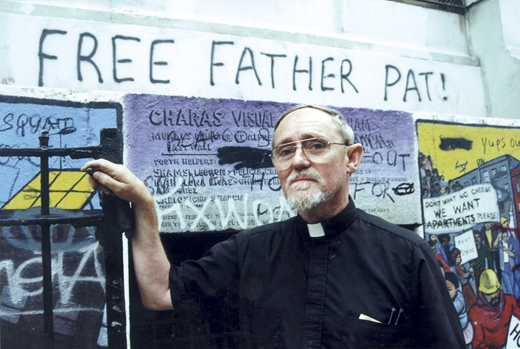

After they split the take, Millar’s main problem was where to hide his money. Under extreme pressure, he approached an Irish priest, Fr. Pat Moloney, who had access to an empty apartment on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. They stashed the money there, where it lay, temporarily unusable, the smell of mint notes giving Millar migraine headaches.

The operation came undone when the FBI got an anonymous tip-off. Agents tailed Millar, Fr. Moloney and O’Connor, duly arresting all three as well as Charles McCormack, the innocent owner of the apartment. The case went to court. O’Connor and McCormack were freed without charge. Millar and Fr. Moloney got off lightly because of a technicality and were sentenced to 60 months. After Clinton’s intervention, Millar was returned to Northern Ireland. He was released from Magilligan Prison in 1997 and has been writing steadily ever since.

Third time around, a new chapter calling.

Millar is invariably asked about the $5 million still unaccounted for. (The main chunk had been stashed in a safe house connected to Millar’s crime partner and that went missing. The owner of the safe house said it was robbed. In all, only about $2 million was recovered). “Everybody asks that,” he laughs. “I’d be out brushing the leaves away and a neighbor would say, `I hope you’re not burying anything there’ — Belfast wit, you know? The thing is, if I had the money I wouldn’t be here in the New Lodge. Some people say it was poetic justice that I didn’t get to keep it, that it wasn’t mine in the first place. I have to laugh at that — I mean, I’ve gone through too much to be offended.

“Certainly I have my regrets. I wrote the book so Tom [O’Connor] and Charles McCormack would be exonerated. For Tom especially, I can’t say I’m sorry enough. I know I shouldn’t have done what I did — if you think about things that were going to happen, you’d never do them. If I knew the FBI would come and stick a gun in front of my nine-year-old daughter telling her to show them where her daddy hid his money, I’d never have done it. They [Millar’s family] didn’t know anything about the bloody money!”

Having literally watched millions of dollars pass through his hands, the curiosity is that he feels happier now. During prison in the U.S., he had time on his hands and found a way to use it by putting pen to paper. A sheaf of handwritten pages on the kitchen table sits like a reminder of the state penitentiary in New York. If writing gave him escape then, it gives him release now.

“Writing the book has given me the greatest satisfaction of my life. It’s been my savior,” he feels, adding that his next two novels are not biographical. “I think I’ve chased enough ghosts. Realistically, if I had never done the Brinks I would never have had the opportunity to become a writer. It’s a terrible thing to say but it’s true.

“I’ve had my gut-full of politics. My daughter goes to an integrated school and we don’t discuss politics in this house. I’m apolitical. I’ve had my fill of it. My wife, three kids, my writing, I’ve got everything and I’m not going to destroy that. I’m not apologizing — I’m more than proud of what I did, but I ask myself, you know, was it worth it?

“There’s nothing romantic about sitting with a bomb under your feet, wondering if it’s going to go off. Of course you should be thinking you’re taking this into a premises and someone else is going to be sitting near it and get hurt. But you’d be thinking in a selfish way. Just thinking of yourself.”

Although frustrated at how slowly political progress is being made, he is enjoying the fringe benefits of his own reform, such as the Belfast launch of On The Brinks at a city center bookstore. The republican author’s cousins came in from loyalist Tiger Bay for the book signing to make it a family occasion on neutral ground. “I think they were just proud that one of the Millar family had got this book out. Some came and others didn’t want to come, but the place was packed. Half of the people were IRA men and the other half were UVF or UDA men and they were all sitting there having a cup of tea. That wouldn’t have happened twenty years ago,” he smiles. “For once we were all in one place.” ♦

_______________

On the Brinks is published by Wynkin deWorde, www.deWorde.com.

Notes

Bloody Sunday: On January 30, 1972, soldiers from the British Army’s 1st Parachute Regiment opened fire on unarmed civilian demonstrators in the Bogside, Derry, killing 13 and wounding a number of others. One wounded man later died from illness attributed to that shooting.

On The Blanket: In 1976 in protest of the ending of special category status and being required to wear prison uniforms, republican prisoners went “on the blanket” (naked except for a blanket). Then in March 1978, fed up with being harassed by prison officers when they went to the bathroom, the prisoners began the no-wash protest and began to daub their excreta on the walls of their cells. The no-wash protest soon became known as the dirty protest. By then nearly 300 republican prisoners were on the blanket. When this proved ineffectual, they decided to escalate the protest, and in October 1980 they announced that seven men would begin a hunger strike to death until their demands were met. Believing a compromise was on the table, they called off the strike after 53 days, with several prisoners near death. The second hunger strike began in March 1981 with Bobby Sands refusing food. By the time that hunger strike ended in October, ten men, including Sands, were dead.

Leave a Reply