For millions of people, June 16 is always an extraordinary day. On that day in 1904, Leopold Bloom made his epic journey through Dublin as described by James Joyce in Ulysses, one of the world’s most highly acclaimed modern novels. “Bloomsday” — the St. Patrick’s Day of literature — has become a tradition for Joyce enthusiasts all over the world.

Nowhere is Bloomsday more rollicking or exuberant than in Dublin, home of Molly and Leopold Bloom, Buck Mulligan, Stephen Dedalus, Gerty McDowell and James Joyce himself. The Irish, who reviled Joyce when he was alive, now reverently tramp the streets of Dublin retracing the footsteps of Leopold Bloom, visiting the various places immortalized by this latter-day Edwardian Odysseus.

But this year Bloomsday was extra special. It is 100 years since that first journey took place, and the Irish are in the midst of a huge, ebullient, multifaceted celebration with the jubilant title ReJoyce. Only the Irish could turn the events of a single day one hundred years ago into a five-month world-class festival, with a spectacular range of theatrical, artistic, musical and educational events.

The Irish Museum of Modern Art is hosting “High Faluting Stuff,” an exhibition of Joyce-influenced art, while the Royal Hibernian Academy presents another exhibition of art and installations by Joyce-inspired artists such as Matisse, Brancusi, Jess, Man Ray and even Joyce himself. The National Library of Ireland is featuring an extensive literary exhibition devoted to Joyce, displaying a number of previously unseen notebooks, drafts, and correspondence. Concerts, plays, a film festival, photographic exhibitions, lightshows, pageant and street-theatricals are all part of the fare planned.

For those who wish to learn something about Joyce, three venues are in the must visit category.

The first is the Martello Tower at Sandycove, (eight miles south of Dublin) which is now the site of the James Joyce Museum. Built as a cannon installation in 1804 against a possible Napoleonic invasion, it is now filled with Joycean memorabilia including rare first editions of his writings (including an edition of Ulysses illustrated by Henri Matisse), personal possessions, letters, documents, photographs and portraits. The top of the tower commands an imposing, and often breezy, view of Dublin Bay, while the room immediately below is still maintained as it was during Joyce’s stay (as a guest) in the Tower. Books, cards and souvenirs are available, with staff on hand to provide a guided tour and answer queries.

Across the city, past Trinity College to Dublin’s north side, is the James Joyce Centre (North Great George’s Street) which is located in a beautifully restored 18th century townhouse. Here a wide range of material connected with Joyce, including rare translations of his work, is on display. Also at the Centre, visitors can books guided walking tours that explore the north inner city — Joyce’s creative heartland.

The last of the three sites, The James Joyce House, on the banks of the River Liffey at 15 Usher’s Island, is still a work in progress. Dating back to the 13th century, it was the home of Joyce’s aunts, and it was here that “The Dead,” one of his most famous short stories from Dubliners, was set and was later brought to the screen in John Huston’s last film, The Dead. Having lain derelict for nearly two decades, the house was saved from the wrecker’s ball by Dublin barrister Brendan Kilty, who is restoring this important landmark to its former glory. When renovations are completed, visitors will be able to stay at Usher’s Island. The venue can currently be hired for corporate functions and intimate Edwardian dinners, similar to those which Joyce would have attended. Art works by leading Irish artists are on display, and guided tours of the house are available.

Re Joyce commenced on April 1 and ends on August 31, bringing Dublin to the focus of world attention. The newly confident, multicultural, refurbished, effervescent, affluent Dublin is seemingly ready not only to embrace its Joycean past, but also to welcome a superfluity of tourists keen to join in and celebrate. This, above all, is the season to visit Dublin to rejoice in ReJoyce.

BLOOMIN’ JOYCE ON FILM

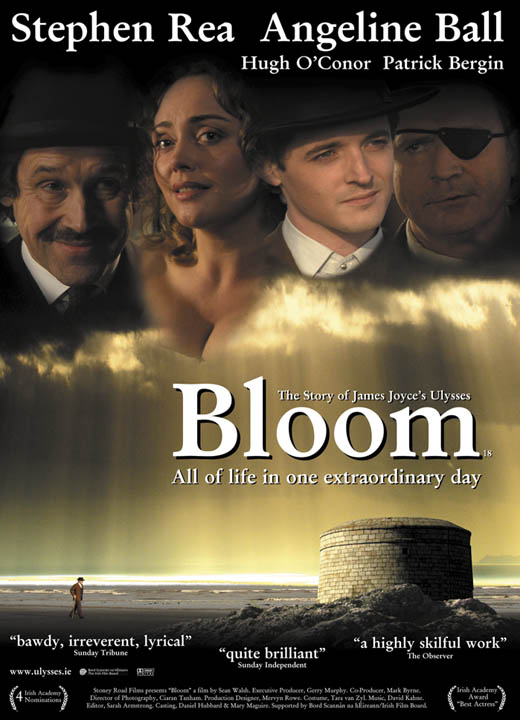

Sean Walsh, the writer, director and producer of Bloom, which stars Stephen Rea as Leopold Bloom and Angeline Ball as Molly, talks to John Hagan. Bloom was screened in New York on June 10 by The Irish Repertory Theatre. At press time, its American distribution was still being negotiated.

John Hagan: Most people give up on Ulysses by page eight. What ever possessed you to make a film of it?

Sean Walsh: For that very reason! I was attracted to the fact that while Ulysses is recognized as the greatest novel of the 20th century, few people have ever read it. I wanted to bring the story to a wider audience, and reveal the humor, and most importantly, the humanity of the novel.

My hope is that anyone who watches it will sympathize with the characters. More importantly, I hope that they will see a part of themselves reflected on the screen.

In a previous film of Ulysses made in 1967, its director Joseph Strick believed that a filmmaker’s duty to great books is to copy them literally. Does your approach differ?

I believe that the filmmaker should remain faithful to the integrity of the text, but I also think that you have to be aware of the medium of film. We begin with a portion of Molly Bloom’s soliloquy and return to the same point in time at the end of the film. In Joyce’s novel, the soliloquy only occurs in the last chapter but I felt that this wouldn’t work for the movie audience.

Bloom is not a big-budget film. How did you manage to attract actors such as Stephen Rea, Hugh O’Connor and Patrick Bergin?

SW: All of the cast, and indeed crew, were attracted by the nature of the project, by the script, and also the opportunity to work on an adaptation of the greatest novel of the 20th century. In terms of direction, my approach was fairly simple — I surrounded myself with a highly talented and motivated cast and crew, and I sought their ideas and input at every stage of the film. Honesty and integrity also played a key part; and the atmosphere on the set was amazing. I can honestly say that I can’t imagine ever doing anything as challenging or exhilarating again.

How faithful have you been to Joyce’s Dublin?

It was impossible, because of budget, to re-create all the areas depicted by Joyce. However, we spent years looking for and securing the right locations in Dublin that would provide us with the right “feel” and “look” for the film.

What difficulties did you face in making the movie?

SW: It was all about money. All about raising the five million euros needed to bring it to the screen. Nobody believed we could actually make a film of Ulysses. ♦

Leave a Reply