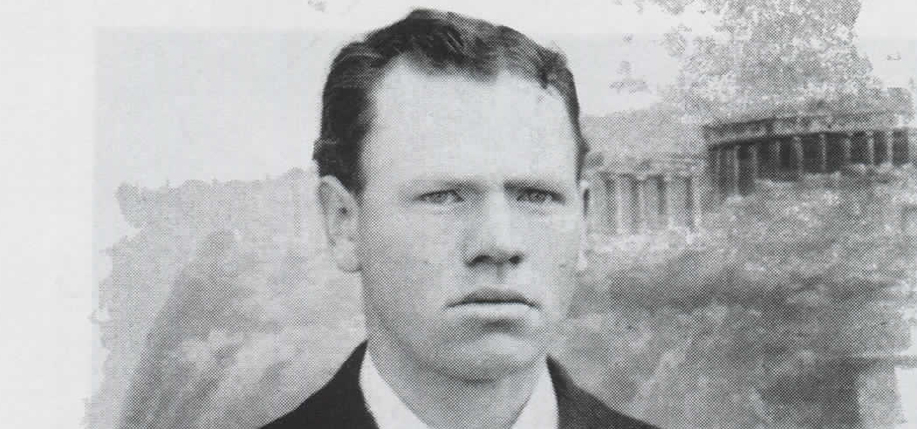

Born in South Boston October 28, 1868 James Brendan Connolly was the sixth son of childhood sweethearts John Connolly and Ann O’Donnell from the Aran Islands off the west coast of Ireland. But in 1895, Jim Connolly’s parents were far from pleased. At the age of 27 their son gave them a great sense of pride when he entered Harvard to study engineering. Less than a year later, he dashed their high hopes by storming out of the university in a fit of pique.

It was his reason for quitting Harvard that drove them almost to tears.

Education at a great academic institution was being tossed aside simply because he wanted to dart off for a couple of months on a crackpot adventure several thousand miles away.

His parents vainly tried to dissuade him, but nothing would make him change his mind. So intent was he on competing at the revival of the ancient Olympic Games that he was prepared to travel to Athens at his own expense.

Before he learned of the Olympics, Connolly had proved himself a hard worker. He had set his heart on making enough money to study engineering at Harvard. So he worked on a harbor development project in Savannah, Georgia. Connolly supplemented his earnings by doing sports reporting for the Savannah Lamplight. He also captained the Savannah football team and helped the Suffolk athletic club from South Boston to win the United States amateur athletic championship. He himself won the national hop, step and jump (later the triple jump) title.

He studied in his spare time. Although his formal education had not advanced beyond grade school, he tutored himself so well that Harvard accepted him as a freshman in 1895.

Some years previously he had read Chapman’s translation of Homer, and this led him to hope that some day he would visit Greece. This hope grew into a fixation the more he learned of the efforts of Baron de Coubertin to revive the Olympic Games of Ancient Greece. When this nobleman invited the youth of the world to Athens in 1896 to compete against each other in a spirit of friendly rivalry, Connolly decided that the opportunity to participate in the revival of the Games was not one to be missed, so he left Harvard.

He and the other American athletes arrived one night in Athens, thinking that they would have twelve days to practice. To their dismay, they learned that the Greeks had their own calendar and that the first Olympic Games of the modern era would be formally opened next day. Even more worrying from Connolly’s viewpoint was the news that, immediately after the opening ceremony, his event — the triple jump — would commence the Games.

The next day, before the event got under way, the entrants were informed of the order in which they were to compete. Connolly was the last name on the list. So, when it came to his final attempt, he knew what was expected of him. Unless he produced an exceptional final effort, first place would go to a Frenchman, Alexandre Tuffere, who had cleared 41′ 8″.

Any other athlete would probably have been shattered by the pressure, but Connolly remained cool. As he himself later remarked, “I was standing between Prince George (later King George V) of England and Prince George of Greece, and the personal magnetism of these two gentlemen was so strong that I said, `Here’s to the honor of County Galway!’ and I jumped.”

Before he actually jumped, he strode up to Tuffere’s mark and threw a cap a yard beyond it. This was a brazen thing to do in front of royalty and of the packed stadium, but Connolly had not come this far nor endured so much simply to give a good account of himself.

He walked back to his starting line. Then he raced down the track and launched himself out to within a quarter-inch of 45 feet.

“Nike!” (victory) the Greeks called out in recognition of his achievement. James Brendan Connolly had become the first Olympic champion since Barasdates of Armenia won the boxing in 369 A.D.

After the Games, Connolly pursued a successful career as a writer back in the United States. He had found his vocation, writing stories about fishermen, boats and the sea. Story after sea story flowed from his pen as if it were the most natural thing in the world, and they were written in South Boston “on one side of the kitchen table while my mother rolled pie crust on the other.”

In 1904, he married Elizabeth Frances Hurley. They had one child, Brenda. Jim died on January 20, 1957, at the age of 88.

During his lifetime Connolly received many awards. Harvard offered him an honorary degree but, with his Irish dander still up, he refused. In 1949, however, he returned to Harvard for a reunion of the class of 1899 with whom he would have graduated had he not gone to Athens.

Possibly the greatest tribute to Connolly came from Theodore Roosevelt who became impressed, not only with his writing, but with the man himself. The President said, “If I were to pick one man for my sons to pattern their lives after, I would choose Jim Connolly.” ♦

Leave a Reply