Her career spanned over seven decades and 60 movies. The camera loved her so much she become known as the Queen of Technicolor. John Wayne found in O’Hara not just the ideal leading lady but a pal. In fact, he called her “the greatest guy.”

Maureen O’Hara is in fine fettle despite having a slight cold. It’s the day after St. Patrick’s Day and she’s ensconced in a suite at the New York Athletic Cub. This bastion of maleness — the NYAC has only allowed women members since the late ’70’s – is exactly where you would expect to find O’Hara, who at 83 has lost none of her feistiness.

Known for her remarkable beauty and her fiery screen persona, O’Hara, the star of 60 movies, came to Hollywood when she was still a teenager, and almost immediately, as she reveals in her new autobiography, ‘Tis Herself she clashed with the men who ran the movie business. In her own words, “I acted, punched, swashbuckled, and shot my way through an absurdly masculine profession…. As a woman, I’m proud to say that I stood toe-to-toe with the best of them.”

Born Maureen FitzSimmons in County Dublin in 1920, one of six children, O’Hara began acting at age six with the encouragement of her parents. Her father was a football player, her mother an actress and singer. At 16 she joined the famed Abbey Players, and was discovered shortly thereafter by the actor Charles Laughton who took her to London and changed her name to O’Hara.

She made her first movie, Jamaica Inn, with legendary director Alfred Hitchcock. Hitchcock also wanted her to star in Rebecca, but she was filming Hunchback of Notre Dame and director William Dieterle refused to change his filming schedule to accommodate O’Hara.

Soon after O’Hara’s arrival in Hollywood she was “sold” to RKO. With little choice over the movies she made, she admits that she made three duds with RKO. She fought against, but did not always succeed, being cast as the pretty female. “Hollywood would never allow my talent to triumph over my face,” is one of the bon mots she offers in ‘Tis Herself.

It was director John Ford who gave her a chance to prove herself a great actress. Their first movie together, How Green Was My Valley, won a total of five Academy Awards, including Best Picture. In all she made five movies with Ford, who used her as his muse for The Quiet Man. She is remarkably frank in ‘Tis Herself, about her relationship with the brilliant but troubled director, and with John Wayne, who found in O’Hara not just the ideal leading lady but a pal. In fact, he called her “the greatest guy.”

O’Hara is also frank about her marriages. She reveals that her first, to George Brown, who later became the father of publishing titan Tina Brown, was unconsummated. And that her second, to Will Price, which produced her daughter Bronwyn, was troubled and deeply destructive. She eventually found happiness in her third marriage, to aviation pioneer Charlie Blair. The first pilot to fly a passenger plane non-stop from Ireland to New York, Blair ran a seaplane company in St. Croix. When he died in a suspicious plane crash, O’Hara took over as president of the airline. Her successful fight to have her husband, who she believes worked for the C.I.A., buried in Arlington with full military honors, is also recounted in her book.

Photo courtesy June Beck.

Not one to back down from a fight, O’Hara also chronicles her defamation suit against the magazine Confidential. It was the first time an actor won a suit against a tabloid. She also struck a blow for her countrymen when she took out American citizenship but refused to cite British as her former allegiance because she was a citizen of Ireland. Her courageous stand soon caused a change in the proceedings, and shortly thereafter natives of Ireland were no longer identified as British in the naturalization process.

Extremely proud of her Irish heritage, O’Hara served as grand marshal of the 1999 New York City St. Patrick’s Day Parade. As she walked up Fifth Avenue the crowd called out “Mary Kate” to her — the name of the character she played in The Quiet Man.

Patricia Harty: Why do you think The Quiet Man is still so popular and has such an effect on Irish Americans in particular?

Maureen O’Hara: Not just Irish Americans, it has a particular effect for Japanese, Chinese, Italian, Spanish, American, Canadians, and South Americans. Everybody in the world loves it because it is a story that could have happened in the countryside of any country. It’s a simple, warm, touching, wonderful story about family and all the squabbles that happen in families. It’s so true to life.

The making of the film was a family affair, wasn’t it?

Yes. John Ford’s daughter was the cutter, his brother in-law was the first assistant director, his brother was the second assistant. Barry Fitzgerald played his role and his brother Arthur Shields played the priest. There were me, my brother Charlie, my brother Jimmy, John Wayne and all of his kids, who were the kids on the cart with me, and Victor McLaglen’s son, who was another second assistant director.

You actually ruptured your disc on that movie in the dragging scene.

Yes. But I didn’t have the operation until a few years later. I had a great surgeon and he made me wear a brace for six months. I was not permitted to take it off. And I’ve had no problem since. Look at all the stunts I did after surgery. The only stunt I never did was ride — if I got up on a horse I automatically fell off. Not like my sister, who was the first woman to win the Emperor’s Cup in Japan in dressage.

If you were to sum up John Wayne in a sentence…

Such a fine man is very hard to sum up in one sentence. He was a decent, fine, wonderful man. He loved his family, adored his kids and was very loyal to his friends. He never let a friend down even if it meant putting himself in danger. There aren’t enough words in the English language to describe a person like John Wayne.

Didn’t he have some Irish ancestry?

Yes. His name was Michael Marian Morrison.

Director John Ford was quite abusive and, in fact, as you reveal in your book, he even socked you one time.

You have to realize that he was very abusive to almost every actor who ever worked for him. Every stunt man, every mechanic and every lighting man. He was abusive if it suited him and what he was after. I used to watch him sometimes and think, “Oh, he is doing that on purpose. He’s after something.” On the set we used to call that “being in the barrel” and every day somebody would be in the barrel. But very few people ever walked out on him. Henry Fonda was one of the few, and that stuntman who became a star, Ben Johnson, walked out on him and wouldn’t work for him again.

But still you worked for him. Why?

He was a genius. He was the finest director any of us ever worked with, and we were proud to work with him and work for him. We realized that he was abusive and bad-tempered and awful but we accepted it and forgave him, and we wondered what his problem was really. And I think his problem was that he wasn’t entirely satisfied with his own life. He wanted to be born in Ireland. He wanted to be a military hero in Ireland’s problems. He wanted to be a military hero in the world’s problems.

(Courtesy Maureen O’Hara Collection)

So you went into it knowing that it was going to be torture, but that the outcome would be worth it.

Yes. But sometimes it was terrible. One day on Rio Grande he was being so awful to John Wayne, just belittling and terrible, and Wayne just stood there with his head down and took it. I thought “Give it to him. Sock him in the jaw.” But Wayne didn’t. I couldn’t stand it. I had to say, “I’m awful sorry, may I go to the bathroom?” I would go there to throw up.

He was abusive to you, yet he wrote you love letters.

You’ve got to realize that the things he did to me had to do with the picture he was doing and my character. He hated my character or he loved my character. When he did a script he totally immersed himself in both the female and male characters and they would inhabit his dreams. And I think the letters that he wrote to me when I was in Australia [and Ford was in Ireland making preparations for The Quiet Man] were to Mary Kate Danaher, not Maureen O’Hara.

You handled it very well. You could have said, “Look at these letters, what’s going on?”

I thought of showing them to Mary, his wife, and I then thought no, that would be foolish, because that would only get her all upset.

And he would make you have these phony conversations with him in Irish.

Oh yes, totally phony. He didn’t speak it at all. One time we were at a big affair in honor of himself, and President Nixon and his wife were there. Ford insisted that Mary sit on one side of him and I on the other. We were sitting there and Ford said to me that we were going to pretend we were speaking in Gaelic. He said, you just keep saying, “seadh, seadh” [yes, yes].

I did what he asked – you have to realize that you couldn’t say no to him. The president finally leaned over and asked “What are you two doing?” and Ford said, “We are speaking in our native language.”

You still have a hint of Irish in your voice.

Well, I am Irish. So that’s it. But I don’t have to worry about it anymore. Making a movie you have someone — usually the script clerk — who says “watch such and such a word so you don’t betray the character you are playing.” I don’t have to worry now.

You don’t have to be Maureen O’Hara anymore.

Yes.

You say in your book that the publicity department really created Maureen O’Hara.

Not just Maureen O’Hara, any actor who was under contract to a studio – a seven-year contract – as we mostly were – the lucky ones. The publicity people are ordered by the studio to see to it that your name is in the paper every day. So they have to think up a lot of phony stories. One time I read that I’d been bitten by a spider, and it never happened at all. But they had to do that. It had to be something that got printed in the paper, so that your name was kept before the public.

The suit that you brought and won against Confidential over a story that you were necking in the back seat of a theater. That was the first suit of its kind.

Yes, I got mad and I went to my parish priest and told him what I wanted to do and he said, “Maureen, you are wrong. We know the truth and that’s all that matters. Don’t do it.” But I went ahead and did it.

I was in Spain making a movie for Columbia studios [at the time of the supposed incident], so I couldn’t have been in Hollywood. All I did was show the judge my passport as proof.

You were a woman ahead of your time in a male-dominated industry. Was it hard?

But I was accepted as a guy! John Wayne said I was the greatest guy he ever knew.

But you were the property of the studio – so you didn’t always have control over what you wanted to do.

Oh, we all were. Anyone under a seven year contract. We were the property of the studio and they felt that we had to do what they told us to do. And if you refused they had the right to suspend you. And suspending you meant putting you off salary and they put you off salary for the duration of the time it took to replace you, shoot the movie and finish it. So there was a long time when you got no salary and you were not permitted to work for any other company anywhere in the world. That makes it kind of difficult to pay your grocery bill.

You really had to do the movies they wanted you to do.

Yes. Once in a while you would stick to your guns and say no. But you had to have enough saved to pay the bills for the time you were going to be off salary.

Because you really did not make that much money.

Oh no, we didn’t. People don’t realize that. But then, money had a different value in that time. But it still was terrible. When I made Hunchback of Notre Dame I was paid a British salary because I was under contract to Laughton. He loaned me to RKO Studios and I received eighty-eight dollars a week.

The first time I ever worked in Ireland I made a pound a week and I was typing tags for bags of wet laundry, and the first time I worked on radio for Radio Eireann, I made a pound a week.

You had a really supportive family. It was unusual at that time in Ireland for parents to encourage their children to go into the arts.

Oh God, yes. I worked in connection with theater since I was six. Our mother was an operatic contralto. My sister Peg was a wonderful soprano. My sister Florrie worked in theater and made movies. My sister Margo’s first love was horses – jumping, competing and dressage. And my brother Charlie studied law and was also in the Abbey Theatre and produced many plays in London, and Jimmy, my younger brother, the baby, was also in theater. So we were a theatrical family. I used to do my homework at the back of the stage at The Gaiety Theatre on the top of Grafton Street when mummy was singing.

It must have been difficult for you when you had to spend those seven years in the U.S. and you couldn’t go back to Ireland.

We couldn’t go back because of the war. And then one day we were told that all foreigners could go back to the country they came from. So I was at the airport within a minute and on my way back home, and when I arrived in Dublin it was such a thrill to be back with my brother and sisters and mother and father. And a couple of days later a message came from 20th Century Fox that I was to get back immediately because I was going to star in a film called Miracle on 34th Street.

Which is of course another classic.

And I was furious and I wasn’t going to go. I was going to risk everything. And then, I thought “no,” I’ve got too many bills to pay, I better go. And then when I read the script I realized it was such a warm, wonderful family story I was lucky to be cast in it.

I also loved How Green Was My Valley, about the Welsh coal-mining town.

That is one of the classic pictures of the world. And a wonderful story is that when it played in Wales, the Welsh choir got on the boat to Holyhead and went to our house in Dublin and serenaded my family. I’d love to have been there but I wasn’t.

Another Ford movie that is a classic is The Long Gray Line.

Yes. It’s based on Marty Maher who used to train the Army cadets. He used to come down to the set almost every day and give me a big hug and a kiss. He’d tell John Ford to leave me alone, and Ford would say why? and he’d say, because she’s my wife [in the film]. He was an old, old man, a charming, lovely old man.

And Tyrone Power played Maher?

He was absolutely charming. He was named for County Tyrone. And so were his father and grandfather who were also actors.

You made your first film, Jamaica Inn, with Hitchcock. What was he like?

A charming, kind, gracious, wonderful man.

(Courtesy Maureen O’Hara Collection)

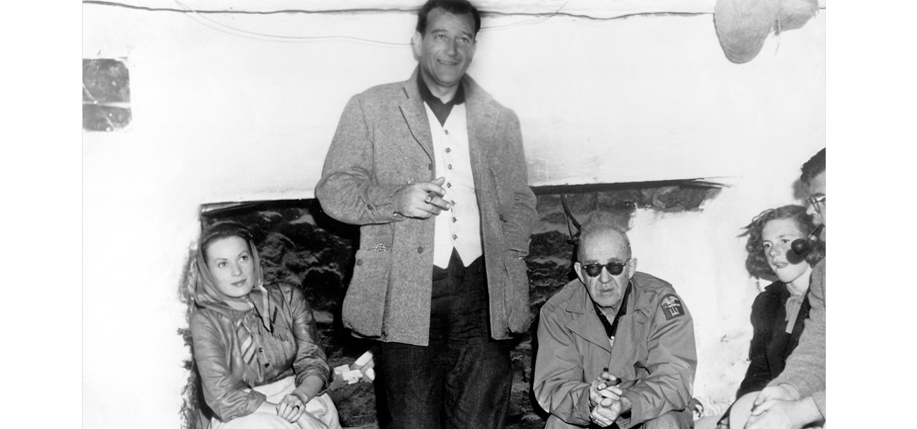

Tell me about meeting Che Guevara.

It was when we were making Our Man in Havana in Cuba. Che Guevara used to come every evening to the hotel we all stayed in for his go-to-bed cup of coffee or go-to-bed whatever. He would sit and talk to me about Ireland. That was his only conversation – Ireland and the battles. He knew everything about Ireland – every mountain road. And he wore the tam like the rebels used to wear in Ireland. He always wore that tam. Finally one day I said to him, “How does a man from Argentina know all this about Ireland?” He laughed and he said, “My name is really Che Guevara Lynch.”

His grandmother, Anna Isabel Lynch, was born in County Galway. He must have learned at his granny’s or his mother’s knee, because he knew everything about Ireland.

Have you enjoyed your life in the movies?

Yes. I haven’t always done exactly the pictures I wanted to do. But I think God has blessed me and I’ve had a wonderful life.

And from the time you were little you knew you wanted to be on the stage.

Yes. When I was six I did a thing at school — when they were changing the scenery, I went out in front and recited poetry. My mother was at one of those [performances] with her accompanist, a lady called Hayden from the next street over from us in Dublin, and she said to my mother, “That girl should be in drama school.” And my mother then sent me to drama school.

Do you miss the stage?

Yes. I was a theater snob. And I thought movies were beneath me. I wanted to be the top dramatic theatrical artist in the theater, but I had no control over that. The other swept in and swept me away.

Would you say the love of your life was your husband Charlie Blair?

Yes. He flew the first land plane with passengers and mail non-stop from the United States to Shannon. And the plane he went over the pole with is in the Smithsonian, and another of his planes is in a New England museum.

He flew the last seaplane out of Foynes and closed that airport. He dipped his wings to say goodbye to Foynes, arrived in New York, got a couple of hours sleep and flew the first land plane into Shannon. He was adored in Foynes. I’ve had people come up to me and say, “My dad was the boatman who used to take all the passengers out to the seaplanes.”

You took over Antilles Air Boats, his airline in St. Croix, when he died. Do you still have a home in St. Croix?

Yes, St. Croix, West Cork, and Scottsdale, Arizona. But the house [the family home] in Dublin is sold. About six months ago.

Does that make you sad?

Yes, but I’ve been so happy in so many years in Glengariff [West Cork].

And you do an annual golf tournament there.

Yes, the end of June and we are now in our 21st years. And then in August. I do the Foynes Flying Boat Museum.

If you had to do it all over again, is there anything you would do differently?

Well, there are a couple of things I wouldn’t do, but I wouldn’t change my life. I think I would sing more than I did. But my career just came like a flood and swept over me and I didn’t get to finish things I really wanted to do. I really, really wanted to sing. I would love to have sung just one opera. Though my voice was a little too high, I would have loved to sing Carmen.

Maybe I would have been more involved in sports. I would have written more, but I would still go for a dramatic career, because that was what I wanted, that was what I planned and that’s what I got.

Do you think actresses today are facing the same problems as you did when the studios just wanted you to do “pretty girl” parts?

I think the problem today is that they are being asked to take their clothes off, and they’ve got to have the courage to say no and believe in themselves.

What’s next?

Staying alive. And of course if some fantastic script came along it would be great. ♦

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the June/July 2004 issue of Irish America magazine. O’Hara was inducted into the Irish America Hall of Fame in 2011. The Hollywood legend was 95 when she died in her sleep of natural causes in her home in Boise, Idaho, on October 24, 2015. She was buried at Arlington National Cemetery on November 9.

From our Archives: Read more about Maureen O’Hara

What Are You Like? Maureen O’Hara

Maureen O’Hara Makes a Sentimental Journey to John Wayne’s Birthplace

Maureen O’Hara: From Santa to St. Patrick

The Many Faces of Maureen O’Hara

20 Great Interviews: Maureen O’Hara

Maureen O’Hara: The Queen of Technicolor

Leave a Reply