Honolulu hosts the very last St. Patrick’s Day parade on earth every year. No other parade is held closer to the International Dateline. It has an eclectic look with Polynesian school bands, Chinese lion dancers, beauty queens of various Pacific Island nationalities and even representatives of the British-themed Fox and Hounds Pub &Grub marching along-side Irish elements.

As Matthew FitzGerald, organizer of the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick’s annual Emerald Ball, puts it, the Irish could never go it alone in Hawaii anyway. They’re too few in number to reject any help offered to carry off a celebration.

The March 17 parade owes its very start to a non-Irishman. Former Honolulu Mayor Frank Fasi, who hails from Italian stock in Hartford, Connecticut, kick-started the event in 1969.

That ended the closest thing Hawaii’s ever experienced to an Irish rebel movement. Dan Sullivan, a native of Worcester, Massachusetts who’s been in Hawaii for 33 years, recalls he was one of a group of Irish insurgents who stayed one step ahead of the law while, under the cover of darkness, painting an illegal green line down the center of Waikiki Beach’s main drag, Kalakaua Avenue.

Sullivan, a retired Department of Education employee, remains at large in Honolulu. He’s a well-known organizer with the Clan Na Gael and Wild Shamrock associations in Hawaii.

The parade has had its share of Celtic eccentricity over the past three decades. Jack Sullivan (no relation to Dan), who left heavily Irish Brighton, Massachusetts, in 1957, cavorts through Waikiki as a leprechaun. He wields a shillelagh, wears green knickers, vest and elfin shoes and goes to the extreme of painting his tongue green.

“What’s wonderful is the love and aloha everyone shares here with the Irish on March 17,” said Sullivan.

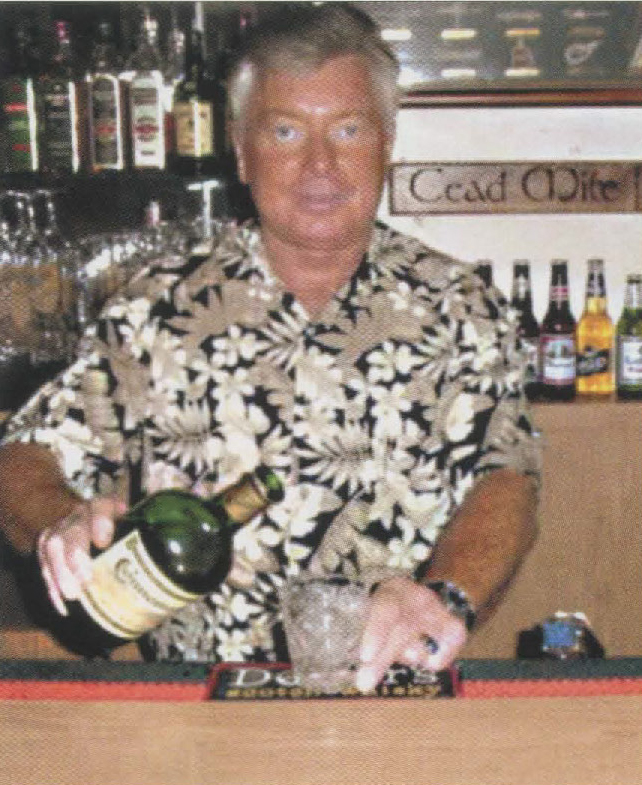

Donegal native John Ferguson, clad in an aloha shirt, serves up everything from Guinness to Bunratty Poteen from behind the counter at his downtown Honolulu Ferguson’s Irish Pub. He sees strong sociocultural similarities between Hawaii and Ireland. “Ah, it’s all the same here except the weather,” said Ferguson, whose place is across the street from the harbor. “It’s the same kind of slow pace here.”

Belfast native Noel Trainor agrees. He’s general manager of Hawaii’s largest hotel (also one of the world’s largest with 3,000 rooms on 22 acres), the Hilton Hawaiian Village in Waikiki. “The people are socially the same here as in Ireland — they love to be with people,” said Trainor, who came to the hotel in 1984. “They will `talk story’ all day with you.”

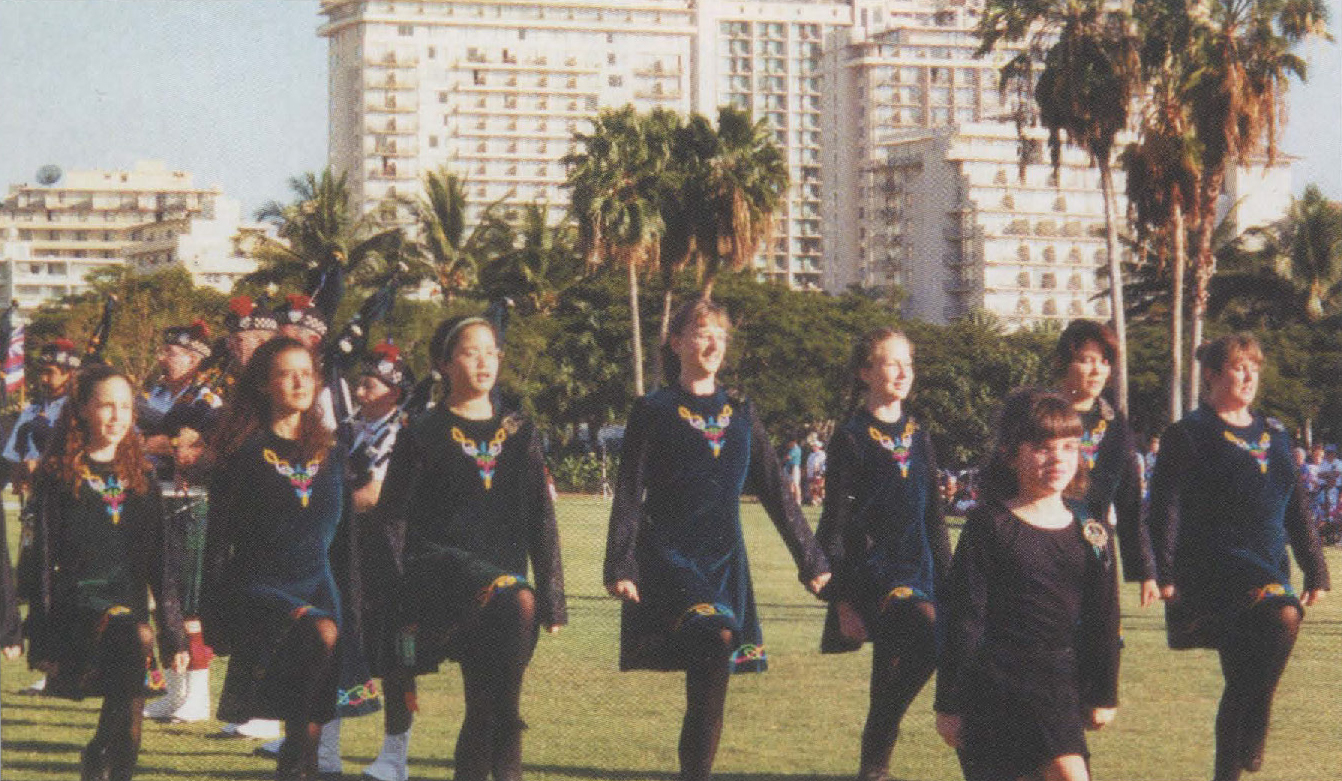

Ferguson said he knew his small, intimate pub across the street from the harbor would go over well when he opened it three years ago. Despite his lack of space, Ferguson often invites Hawaii’s only step-dancing group to hold ceilis there.

“It’s so narrow inside we have to dance by the bathroom door,” chuckled locally-born Annette Murphy Johansson, who organized the group four years ago. Johansson (whose husband is from Sweden) runs the Jig This! School of Irish Dance. She has about 40 members ranging in age from five to 45, representing a rainbow of national origins. One of her best dancers is Thai-German Melanie Held. The group is sometimes accompanied by promising 15-year-old dancer/fiddler Audrey Knuth, whose parents moved here from Washington D.C.

Waikiki Beach has two Irish pubs. Connecticut native Bill Comerford and Rhode Island native Fred Remington, co-owners of the Irish Rose Saloon and Kelley O’Neil’s, will give a gig to any vacationing Irish musician.

Comerford and Remington also recently acquired O’Toole’s, an establishment on the outskirts of Honolulu’s Chinatown with the look of a Dublin watering hole.

Murphy’s Bar and Grill, located across the street from O’Toole’s, has been in operation as an Irish-themed establishment since 1987 and hosts an annual St. Patrick’s Day block party.

Celtic influence in Hawaii extends to Maui where Mulligan’s Irish Pub and Restaurant holds a traditional session every Sunday night. Manager Kevin O’Kennedy plays the pennywhistle.

True to Hawaii’s multi-ethnic Celtic thrust, the state’s most experienced and talented Irish fiddler happens to be a Cherokee-French clinical psychologist.

Lisa Hancock Gomes who grew up in Woodstock, New York, has studied under fiddle legend Martin Hayes and has played at the Willie Clancy Festival. “Irish music resonates deep inside people,” said Gomes. “You don’t have to be Irish to appreciate the music.”

The Irish are known to have been in Hawaii as early as 1794. The first two governors after statehood were Irish-Americans William F. Quinn (1959-62) and the late John A. Burns (1962-74). Maurice J. Sullivan, who founded Foodland, the state’s first supermarket, immigrated from Clare. He eventually opened 100 retail stores in Hawaii before his death in 1998.

The current Honolulu police chief, Lee D. Donohue, is Irish-Korean. Donohue is representative of the islands’ cultural melting pot, which has produced a number of prominent “hapa,” or mixed racial background, Irish-Americans.

Jacksonville Jaguars offensive lineman Chris Naeole, born and raised on the north shore of Oahu, is Hawaiian-Irish. Former Baywatch actor and Honolulu native Jason Momoa is also Hawaiian-Irish with some German mixed in. Yet another Honolulu native often in the news, New York Mets outfielder Benny Agbayani, claims Irish in his blood along with Filipino, Samoan and Chinese. But the Irish-American who probably had the most universal impact on Hawaii was a Brooklyn-raised tough named John Joseph Patrick Ryan. He was better known as Jack Lord, whose Hawaii Five-0 series ran for 12 seasons on CBS and did wonders for the state’s economy. He died in 1998.

Today’s residents of Irish heritage represent only 5.9 percent of Hawaii’s population. But, as in every other part of the world touched by the Gaels, the Irish of the 50th state have made their presence known.

THE LITTLE PEOPLE IN HAWAII

Something Hawaii has in common with Ireland is extensive mythology with similar characters. Both Ireland and Hawaii have “little people.” Native Hawaiians attribute just as many magical powers and good deeds to the “menehunes” as the Irish do to the leprechauns.

The menehunes are never seen and that’s because legend has it they do their best work at night. Many ancient stoneworks are supposed to have been crafted by the Polynesian wee folk who worked by the light of the moon.

Additionally, Ireland has the banshee and Hawaii has Madame Pele, the volcano goddess who is prone to sudden fury, devouring land and structures with molten lava, and sometimes appearing as an ominous old woman on dark, lonely highways. The traditional way of appeasing Madame Pele is by dropping a bottle of gin into the volcano. ♦

Leave a Reply