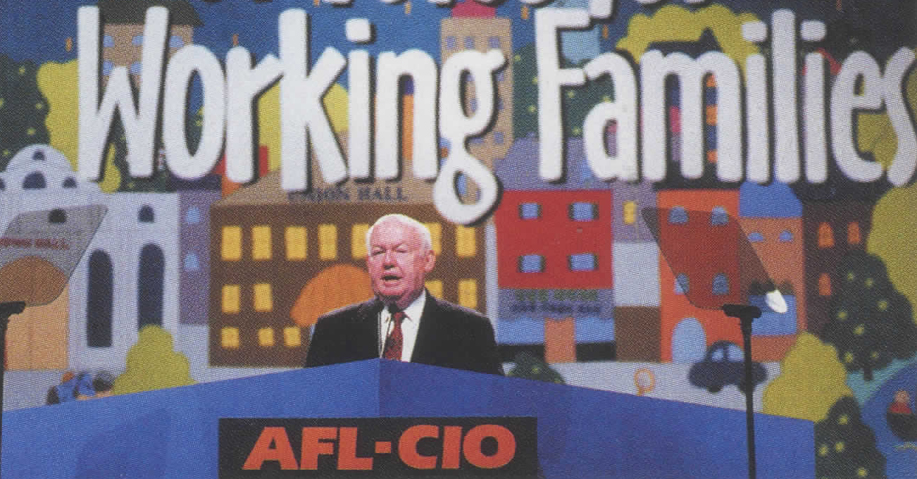

In March, 2004, John Sweeney, then president of the AFL-CIO with three million workers under watch, was Irish America Magazine’s Irish American of the Year. In this far-reaching interview with Sarah Buscher, then Irish America’s assistant editor, Sweeney talked about the plight of immigrants; working families; and growing up in the Bronx, the son of Irish immigrant parents. Back then, as now, a presidential election was looming. His ideal president, Sweeney said, would be “one who would focus on the broad diversity and demographics of our country and address the issue of workers and their families.”

Sitting with me in the sleek conference room of the AFL-CIO’s executive suite overlooking the White House, John Sweeney presents a striking contrast to his surroundings. Portly in his suspenders and rumpled shirt with his jacket nowhere in sight, he appears totally unassuming. It would be easy to underestimate the man at first glance. The only way to gauge his emotions is by his passionate discourse on the present government, and right now he’s on a roll.

“What we’re seeing today is an administration that is probably the worst on working family issues and certainly the most anti-union that we’ve seen since Herbert Hoover. We’ve had Republican administrations where we’re on different sides during the election, but after the election we at least attempted to work together on issues,” Sweeney asserts.

“If you look at the present policies, whether it’s tax or trade, or even the current situation where they’re looking for an economic recovery that’s really jobless, they’re not focused on dealing with employment, dealing with the loss of jobs. But the job loss, especially in the manufacturing industries, has been in the millions in the past two years,” he continues.

Sweeney was elected president of the AFL-CIO in 1995. It marked a high point in a career, and lifetime, devoted to social justice and organized labor. Formed in 1955 with the merger of the American Federation of Labor and the Congress of Industrial Organizations, the AFL-CIO is the umbrella organization for 64 member unions working in almost every part of the economy and has a membership of more than 13 million American workers.

For many years organized labor suffered from the perception that unions were corrupt and didn’t serve the actual interests of workers. The Nov./Dec. 2002 issue of the National Right to Work Newsletter (an anti-union organization) called the AFL-CIO “a multibillion dollar, forced dues empire,” and referred to Sweeney as a “a tin-eared dictator” out of step with the real concerns of American workers. Still, in spite of its detractors, the AFL-CIO added almost a million new members in the past two years.

And to the foes of organized labor, Sweeney hats proved a shrewd opponent using surprise, spontaneity and no shortage of creativity to drive his points home. To celebrate his election as president of the AFL-CIO in 1995, he led an impromptu march up Fashion Avenue in New York City to protest wages and working conditions in the garment industry. He’s been known to even buy stock in a company in order to attend the shareholders’ conference and confront the company president on labor issues and he averages about one arrest per year for acts of civil disobedience.

“I have enormous respect for John Sweeney,” states Senator Edward Kennedy. “The AFL-CIO’s voice as a powerful advocate for progressive public policy and the interests of working families is due largely to the strong leadership and determination of John Sweeney, and all Americans are in his debt.”

In a 1997 interview with The New Republic, political consultant Don Sweitzer compared Sweeney to guerilla leader Che Guevara, “He is an old-fashioned, confrontational union organizer who is not afraid to use unpopular methods to get to the bottom line.”

“We had to do things differently,” Sweeney acknowledges. “Everything around us wats changing. In the 1994 election we saw what Newt Gingrich was able to do and if anything it scared the hell out of us. So I set out to build a stronger labor movement. We had to grow. If we didn’t we weren’t going to be effective politically, and we weren’t going to be effective in terms of collective bargaining in different industries.

“We could never match the opposition in terms of money,” he continues, “but we had people power and we started a campaign to raise the focus among grassroots activists and rank and file workers. In Clinton’s 1992 election, union households were about 16 or 17 percent of the total electorate. We realized that that had to increase. So in 2000 with Gore’s election, we increased the percentage from 16 to 26 percent of union households who voted.”

The AFL-CIO also encouraged its members to run for political office. “We’re now up to about 5,000 people [in office]; they’re in state legislatures, they’re in city councils, boards of education and three are members of Congress,” Sweeney proudly reports, adding, “Although we haven’t endorsed a political candidate [for the 2004 presidential election] we’re out there training workers to be involved in the campaign and they can go and work for any candidate they want.”

Now serving his third term as president, John Sweeney was raised on the teething ring of organized labor.

Born in the Bronx, the oldest of four children of immigrants from County Leitrim, Sweeney credits his passion for social justice to family, faith, and his Irish heritage. “Growing up in this happy, very modest home, family, faith, and heritage were important to us. [My parents] were both Irish immigrants, so we grew up in that culture, and social justice was a big thing. It was something that I felt very strongly about, and in my youngest days I could draw the contrast between my father being a member of the union and my mother a domestic worker with no union, and no benefits.”

Sweeney’s father, James, a city bus driver, wats a dedicated member of the Transport Workers’ Union and a huge fan of its founder, another Irish immigrant, Kerry-born Mike Quill. “We grew up in an atmosphere of him relating his improvements on the job to his union membership,” Sweeney recalls. “I remember we’d go to Rockaway Beach in the summertime and rent a cottage there. My father couldn’t join us all the time because he could only get a week’s vacation or ten days at a time. But I remember [one year] he said, `I can stay two weeks. Our last contract gave me so many more days of vacation time.'”

As a teenager Sweeney attended union meetings and activities with his dad and campaigned for labor candidates at election time. He went on to study economics at Iona College in New Rochelle, New York, the first in his family to attend college, and worked his way through school in a union job as a grave digger. Unable to find work with any of the unions after graduation, he did a brief stint at IBM before landing a position as a research assistant with the Ladies Garment Workers Union. “I was making ninety dollars a week at IBM,” he recalls. “The garment workers offered sixty dollars and I jumped at it.”

In 1961 he joined the Service Employees International Union in New York City as a union representative. Working his way up through the ranks, Sweeney was elected president in 1980. Under his leadership the SEIU’s membership rose from 625,000 to 1.1 million at a time when union membership was declining overall. In 1995, he drew national attention when he led striking janitors in a sit-in on the 14th Street Bridge in Washington D.C. during morning rash hour.

It was Sweeney’s success with the SEIU that prompted other labor leaders to nominate him for the presidency of the AFL-CIO.

Throughout the 1980s the AFL-CIO’s membership steadily declined along with the political weight it carded on Capitol Hill. Sweeney’s history of activism and agitation seemed to be just the thing needed to rejuvenate the federation and he was elected to the office in 1995.

Once in power, Sweeney embarked on a massive campaign to enlist new members, earmarking one-third of the AFL-CIO’s annual budget for this effort, and to politicize the masses. Long believed to be the bastion of white men, the union underwent a facelift under Sweeney with new leadership opportunities for women and minorities.

“We had to change the perception of our members. They had to be more knowledgeable and educated about the labor movement, about the issues, and we also had to change the perception of the public,” Sweeney recalls.

The struggle for an ideal is invariably uphill, requiring equal doses of inspiration and pragmatism. For Sweeney, the ideal is social justice. Throughout his life he has been a tireless advocate for workers’ rights: fair wages, good jobs, health care, retirement security and corporate accountability. It’s all part of the American dream — the dream of Sweeney’s own immigrant parents.

“Our country’s been built by immigrant workers, we’re all immigrants or the product of immigrants,” Sweeney points out. “And we’re all very proud of our roots, but the way we’re treating the present millions of immigrant workers in our country is a disgrace. Immigrant workers are being exploited even more than they have ever been in our country.”

The only solution to the immigration problem right now is to have true immigration reform, Sweeney asserts. “[Reform] which guarantees every worker the protection of the law to prevent them from being exploited. If these workers are in a low wage job, they should be getting whatever the legal minimum wage is and not something below that. If they’re working overtime, they should be entitled to overtime pay.”

To draw attention to the plight of immigrant and undocumented workers, the AFL-CIO sponsored the Immigrant workers Freedom Rides last October. Modeled after the Freedom Rides during the civil rights movement of the 1960s, these demonstrations drew scores of buses from across the country to rallies in Washington, D.C. and New York.

The issue gets raised about whether immigrants are going to replace workers in current jobs, Sweeney acknowledges. “I know workers in some industries are nervous about that. But it’s safe to say that millions of immigrant workers are working in some of the lowest paid service jobs, farm jobs, domestic workers, office building cleaners, hotel and restaurant workers and so on. They’re not depriving anyone of a job, those are jobs that are available, and I think that the paranoia has to be relieved. Policy makers who know that this is the situation have to stop using that as an argument against the legalization of immigration. [We need to] solve the legalization question, the amnesty question, and deal with these workers as human beings. Don’t pit them against someone who was born in this country.”

The traditional view of labor as a bastion for the preservation of American jobs might seem increasingly irrelevant in a world moving toward globalization, but not John Sweeney’s labor.

He feel that the AFL-CIO’s demands for social justice are more necessary than ever in a post-NAFTA world. Ten years after the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement, the country is debating its costs and benefits. The AFL-CIO opposed the agreement along with the Central American Free Trade Agreement and the Free Trade Areas of the Americas Agreement, and Sweeney explains why:

“Our message is that trade agreements have to include core labor standards and environmental initiatives. Ten years ago we opposed NAFTA because it really didn’t provide for core labor standards or environmental protections. We’re talking about workers in those countries having the ability to assemble, to organize, to fight child labor, and forced labor. These are basic human rights that the ILO [International Labor Organization], and the United Nations have adopted and we think that these basic rights should be in every country and we should do everything in our trading negotiations to try and strengthen that.

“We’re as concerned about the developing world as anybody else is,” Sweeney asserts, “and we have to deal with the issues of the developing world. One of the ways we can deal with it is in terms of trade and also paying more attention to debt relief for developing countries. We recognize the fact that trade is very important to our country, to the economy, and to our trading partners. If we can protect capital and we can protect property rights in our trade agreements, there’s no reason that we can’t make it work for working families. We’re not talking about imposing our economy, our minimum wage, or our standards on our trading partners. Globalization is here to stay and it’s going to continue to grow. We’re more involved globally than we’ve ever been because that’s the direction that business and public policy are going.”

And here in the U.S. Sweeney says the need for a stronger voice for labor is as dire now as it ever was. “Half the people in this country who are in jobs that fall into the category of worker, not management, would join a union if they had the opportunity. It’s not about whether a union has approached them, although that’s part of it, it’s about their employers really put pressure on them not to join a union. There are thousands of cases each year where workers are fired because they are stimulating union organizing activities,” he emphasizes.

“Just look at Homeland Security,” Sweeney continues. “They have increased the number of airport screeners, which is necessary, but they won’t allow them to join unions, they have disallowed them any opportunity to organize. They have excluded 700,000 defense workers who will not be allowed to join unions or to participate in collective bargaining.”

And while Sweeney recognizes that there have been some modest improvements in some areas in terms of the economy, the job situation is bad, he says. “We have displaced steelworkers whose plants have closed and they’re flipping hamburgers at McDonald’s part-time. That’s really a disaster for our country,” he declares firmly.

With the primary season heating up, and the AFL-CIO preparing to endorse a presidential nominee, Sweeney says his ideal president would be “one who would focus on the broad diversity and demographics of our country and address the issue of workers and their families.” He adds, “We have to have a country that’s productive, that is going to be successful in business and the economy and give everybody the hope, the dream of having a good decent life, with education, health, retirement security and a decent standard of living. We’ve done that before and we certainly, as the strongest industrial country in the world, and the strongest democracy, have the ability and potential to do it again.”

In a 1997 interview with Irish America, Sweeney described the America of his childhood: “There was the feeling that if you worked hard, you could get your decent share, you were able to afford certain things, you could get your kids educated. You may have been poor or a member of the working class, but there was still this feeling of hope.”

Now, more than seven years later, Sweeney states, “I would add to that quote that you could expect a decent retirement.” Retirement security is no longer a sure thing for anyone and Sweeney blames corporate greed.

“The Enron situation was an example. Here were people who were decently paid, enjoyed their work, played by the rules, paid their taxes, raised their families, moved up in the company, got promoted and overnight were thrown out on the street. They lost their retirement — hundreds of thousands of dollars in many cases — lost their homes and college funds. That’s a national disgrace.” In the wake of the Enron debacle, Sweeney and the AFL-CIO succeeded in negotiating a settlement for workers for a total of approximately 35 million dollars.

It’s victories like this that sustain him, improving the lives of all Americans, one worker at a time, one family at a time. “The best part of this job is the satisfaction in helping workers,” he points out. “In my earliest days if I could get somebody his job back after he was terminated, or organize a new worker who was making minimum wage and double his salary and his benefits as a result, I was happy. This is very satisfying kind of work,” he asserts. “Whatever the problems are, there’s not a day when I am not eager and really anxious to get to work.”

Note: Some weeks after this interview the AFL-CIO endorsed Presidential candidate John Kerry. IN 2009, John Sweeney stepped down as president of the AFL-CIO at this Convention, after serving in office for nearly 14 years.♦

Return to Labor Day 2020 to read more.

Leave a Reply