As we commemorate the anniversary of the birth of Irish writer Brendan Behan in 1923 on February 9, Elizabeth Toomey writes about his time in New York.

On September 3, 1960, the New York Daily News carried a photo of a beaming Irish playwright arriving at Idlewild airport was a glass of milk in his hand. It was Brendan Behan, on his first trip to America. The milk was the result of an attempt by Behan and his handlers to downplay his reputation as a rowdy drunk. Behan was on top of the world. Just before he got on the plane, he heard that his best-selling first novel would be published in paperback with a large advance. Now his play, The Hostage, already a hit in London, was about to make its Broadway debut. Less than eight weeks later, the News ran another photo of Behan staggering onstage, along with the gleeful headline, “Behan Back on Booze Binge, Goes Into Orbit in Theatre.”

But the brief months between Behan’s arrival and his fall from grace constituted a golden period in his life. Behan and his wife, Beatrice, fell in love with New York unequivocally at a time when all things Irish were enjoying a fashionable period. Tommy Makem and the Clancy Brothers were appearing on The Ed Sullivan Show and at Carnegie Hall, singing Irish folk songs in Aran sweaters, and inspiring up-and-coming folk singers, including the young Bob Dylan. And John F. Kennedy was about to be elected president. The Irish were being celebrated by mainstream New York more than ever before. (Angela’s Ashes and Riverdance were still more than thirty years away!) The warmth Behan experienced from New Yorkers is reciprocated in his travel book, Brendan Behan’s New York, where he tells of a tourist he spoke to who liked to come to New York for a visit, “but was impertinent enough to say that he would not like to stay there. I am sure that a lot of my readers would express the same sentiment. My reply to one and all is: Well, who sent for you?”

Although often pigeonholed as the “Irish Dylan Thomas” because of his drinking, Brendan Behan holds a firm foothold in Irish cultural history. His mother worked as a maid for Maud Gonne (the object of W. B. Yeats’s affection and subject of many of his poems), his father served jail time for Irish Republican Army activities, and his uncle wrote the Irish national anthem, “The Soldier’s Song.” Born on Dublin’s Northside on February 9, 1923, Brendan was an entertainer with the ability to reel off poems and songs from an early age; Robert Emmet’s “Speech from the Dock” was his party piece. His republican background inspired his first writing efforts, published in an IRA youth newspaper. He joined Fianna Eireann, the Irish nationalist answer to the Boy Scouts, at eight, and at sixteen he was learning bomb making at an IRA training camp.

In the summer of 1939, he was sent to England to participate in a series of IRA bombings but was quickly arrested and sentenced to three years at a borstal institution, a reform school for boys. If he had been one day older (he turned 17 the day after his trial) he could have been sentenced as an adult for up to 14 years. As it turned out, the borstal proved a positive experience, with its disciplined sports, studying, regular meals, and well-stocked library.

Behan was back in Dublin only six months before running into trouble with the law again. This time he was arrested for the attempted murder of two policemen following a fracas that developed during a march commemorating the 1916 Easter Rising. He ended up spending nearly four years in Dublin’s Mountjoy Prison. With plenty of time to write, he began what would be published more than ten years later as Borstal Boy, an autobiographical novel about his years in England. Through mutual friends, his work caught the attention of Sean O’Faolain, editor of The Bell. O’Faolain published Behan’s first essay in 1942 when the writer was still a nineteen-year-old prisoner.

Out of Mountjoy in 1946, Behan supported himself with house-painting jobs and occasional journalism, but he also made a name for himself as a raconteur in the literary salons of the day: Dublin pubs such as McDaids, The Bailey, and The Pearl. His first major success was The Quare Fellow, a prison drama inspired by the execution of a fellow prisoner from Mountjoy. After its debut in Dublin in 1954, Behan was hailed as the next Sean O’Casey, and his reputation was established in Ireland.

In 1955, Behan married Beatrice French-Salkeld and settled down for a comparatively sober year during which he finally completed Borstal Boy. He became a regular on Radio Eireann, contributing to programs on Dublin history and folk music. Three years later, he made several memorable television appearances on BBC and NBC. During one interview with Edward R. Murrow, Behan was considered so drunk that he was cut off in the middle of an impromptu song, and his disappearance mid-show was explained as a “technical difficulty.” (The other guest, Jackie Gleason, said Behan was “coming through here one hundred proof.”) While he was angry at being cut off, and television executives were dismayed, audiences seemed to love these irreverent interviews. By the time Behan arrived in New York for the Broadway debut of The Hostage, he had perfected the art of playing the stage Irishman, and New Yorkers were ready for him.

The Hostage, centered on a captured British soldier held in a Dublin lodging house, received many standing ovations on its Cort Theatre debut, and the playwright got more when he entered Sardi’s, and later, Jim Downey’s Steak House for opening night celebrations. The play took in $24,000 in its first week and soon moved to the Eugene O’Neill Theatre for a long run. During this time, Behan relished getting to know New York’s Irish pubs, most notably McSorley’s, P.J. Clarke’s, and Costello’s of Third Avenue — at first limiting his drinking to seltzer and orange juice. He delighted in befriending American writers and celebrities such as Norman Mailer, Arthur Miller, and Jackie Gleason. Three appearances in as many months on The Jack Paar Show made him an instant celebrity in New York, if not the rest of the U.S.

Bernard Geis, Behan’s American publisher, and patron, remembers Behan as a rowdy but lovable party guest who would burst into song at the slightest provocation. “I said to him, `Brendan if this is the way you behave when you’re sober, then what are you like when you’re drunk?’ And he said, `Oh, just the same as this, only I fall down.'”

Apparently, it was an argument with his wife about an expensive Brooks Brothers coat that started Behan’s fall off the wagon on October 26, 1960. He began drinking during a late lunch and, reportedly, seven bottles of champagne later he turned up at the Cort Theatre an hour into the play and roared onstage to deliver an incomprehensible speech. The actors tried to play along with him, continuing with their lines, but the scene degenerated into chaos and ended with a fistfight between the stage manager and a Daily News photographer. The News article took delight in the fact that Behan was returning to his loud, ebullient, drinking ways. “He was beautifully biffed and the audience loved it,” the article noted.

But not everyone was charmed by Behan’s behavior. After his binge, the Algonquin Hotel threw him out, and after more drunken episodes, he became persona non grata at other hotels and bars as well. In 1961, Judge James J. Comerford of the St. Patrick’s Day Parade Committee (with the support of “lace-curtain Irish” who tried to distance themselves from traditional Irish stereotypes) refused to allow him to march down Fifth Avenue, calling him a “disorderly person.” He had to make do with marching in Jersey City instead. The Daily News, which seemed to go out of its way to put him down, editorialized, “For our part, we’re glad Justice Comerford thumbed Behan to the sidelines. Tomorrow’s parade should be much better for the absence of a show-off…Jersey City, you can have him.” Behan retorted in Newsweek that “I now have a new theory on what happened to the snakes when St. Patrick drove them out of Ireland. They all came to New York and became judges.” But, public rhetoric aside, with pressing obligations to projects that he hadn’t begun, the pressure to perform the role of consummate Irish character became a burden. As Behan complained to one friend, “Success is damn near killing me.”

His drinking was becoming more problematic and he experienced several diabetic comas after binges. Despite hospitalizations and a series of drunken fights and arrests, Behan continued to drink, using the excuse, “Alcoholics die of alcohol.” Writing became more difficult, and in late 1960, seeing no sign of the contracted Brendan Behan’s Island (a travel book on Ireland), his London publisher sent Rae Jeffs to tape-record Behan rather than wait for a manuscript. It signaled an end to his writing career; his final two books, Confessions of an Irish Rebel and Brendan Behan’s New York, were also compiled from taped interviews by Ms. Jeffs. When asked if Behan was disappointed that he had been reduced to dictating his words into a tape recorder, publisher Geis said, “He was lucky to get it on paper at all. He cooperated the best he could.”

Between 1960 and 1964, Behan made four extended trips to New York, many of which were spent at the Chelsea Hotel. Some were ostensibly linked to openings of his plays, or interviews with Ms. Jeffs for his books, but much of the time it seems that Behan was drawn to New York because of the adulation he received here. Possibly he was also getting away from Dublin, where many of his so-called friends would routinely buy him drinks during his attempts at sobriety because they enjoyed his drunken antics. As Norman Mailer told Behan’s biographer, Michael O’Sullivan, “There was no particular purpose to Brendan’s being in New York, except to escape being in Dublin.”

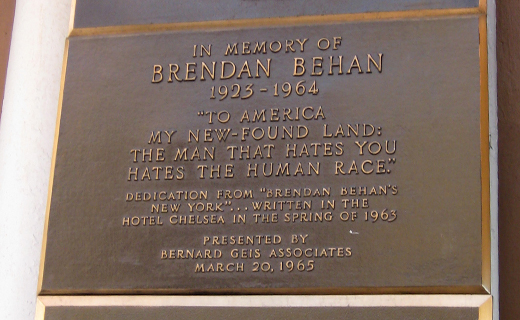

His last years were filled with outward successes; Borstal Boy was a bestseller, and his plays appeared to enthusiastic reviews on London’s West End and Broadway. A daughter, Blanaid, was born in November 1963. But Brendan Behan was succumbing to a deadly combination of alcoholism and diabetes. He finally died in Dublin on March 20, 1964, aged forty-one. As he had predicted in childhood, his funeral was large and full of the leading figures of Irish society. Eamon de Valera and the Lord Mayor of Dublin, as well as IRA friends and theater colleagues, were in attendance. Bernard Geis erected a plaque outside the Chelsea Hotel that memorializes Brendan’s time there. One of his friends and fellow writers, Flann O’Brien, wrote in the Sunday Telegraph:

“Brendan will not be replaced in a hurry, or at all…. He is in fact much more a player than a playwright, or, to use a Dublin saying, `He was as good as a play’. One can detect some affinity in him with O’Casey, but the pervasive error lies in ranking a delightful rowdy, a wit, a man of action in many dangerous undertakings where he thought his duty lay, a reckless drinker, a fearless denouncer of humbug and pretense and so a proprietor of the biggest heart that has beaten in Ireland for the past forty years.” ♦

Brendan Behan is the son of Kathleen Kearney Behan, herself a political powerhouse, raconteur, and gifted singer who, in the course of her long and often tragic life, managed to have a bit of fun along the way. Read about Kathleen in Rosemary Rogers, Wild Irish Women: Dancer in a Rough Field.

Wonderful article. The reel to reel tapes and typescripts for Brendan’s “Confessions of an Irish Rebel” are in the archives of The American Irish Historical Society.

Loved his book”Brenda Behan’s New York” Especially the part when he was in a Jewish club’s shower room and a telegram came for him.

As they say” he was his own worse enemy”.