It looks like it’s trying to clear this morning, though waves of drizzle betimes pass through. Our friend Thomas says “betimes.” I like it.

A little while ago our neighbors Anne and Joe Kelley stopped to tell us that Joe Macklin had died during the night. The Macklins live in the small house on the crossroads at the end of our lane, where we turn to go into Roscommon. It’s known as Macklin’s Cross.

Such is the closed nature of rural Irish life that we didn’t even know Joe was ill; no one had ever mentioned it, whether for privacy’s sake or from some ingrown sense that such things just aren’t talked about. We only knew that the Macklins didn’t seem as “outgoing” as other neighbors — which, now that we know why, is understandable. Apparently Joe had suffered a series of strokes and was totally incapacitated for the last six years. His wife and children had been taking full-time care of him all these months.

That Joe and Anne had thought to stop and tell us was, in itself, a remarkable gesture — they would have known that we hadn’t heard the news, but they knew too that we might not realize it was expected we go to the wake. In Irish fashion they were a bit obtuse about the details, leaving us to wonder during the afternoon, “should we go? Isn’t it kind of presumptuous…I mean we didn’t even know the Macklins except in passing.”

And so we “researched” home wakes; that is, we called our friend James and then Thomas. What’s a wake like? Is the body there? What happens? Do you bring something? What time do we go? Joe only died this very morning, what about the family’s privacy?

Joe Kelly had laughed aloud when I’d asked him about that. “Ha! There’s no privacy here in the country! You’re neighbors. You go.”

And so it was agreed that Thomas should probably go with us to avoid the probability that one of us would offer our profound condolences to the wrong person. We determined to go in the evening, not too early/not too late, and so during the afternoon I made some buttermilk biscuits to take, with ajar of wild blueberry jam, as an “offering from Maine.” Later on we have our dinner as usual, and sit down to wait. Finally after nine p.m., and just as we’re wondering if he’d show up at all, Thomas bounds across the kitchen window view. A farmer’s life of leaping over stone walls has given him springs for legs. “It’s early yet,” he says, “but the weather’s cleared and we can go.”

There is something old-world about walking up the lane under a rising moon, carrying food to such a solemn occasion. Ahead of us we can see the sweeping headlights of arriving cars, hear the clunk of doors and the hushed conversations of people crossing the yard. I think of N.C. Wyeth’s painting Island Funeral. Everyone converging on the saddened house from a surrounding sea of darkness. I dig my nails into my palm…don’t cry for god’s sake, how stupid would that be? But we all have wells of untapped sorrow.

As we finally step into the kitchen courtyard I see people lining the walls inside. I don’t recognize any faces, and begin to panic that I will embarrass myself by not recognizing people I’ve already met. I always have trouble with small talk in any case and it suddenly seems a bad idea to have come. But it’s too late. The door opens before we even knock, and hands reach out to greet us.

The kitchen seems hot after walking in the cool night air. There’s a turf fire in the range and the room is packed with family: three sons, five daughters, assorted grandchildren, aunts, uncles, and cousins of all remove. Though it’s a slightly solemn time, the friendliness is unrestrained. Someone takes us each in hand and introduces us all around. Relationships are thoughtfully explained. We offer our condolences, and pass the pleasantries of weather. It gets easier. Simple platitudes are shared and touched like rosary beads; a reaffirmation, gratefully exchanged, of basic and comforting truths.

A steady hum of hospitality weaves around us. Women making tea and coffee, men bringing in more chairs from the sheds and neighbors delivering cartons full of cups and glasses, carefully wrapped in fresh tea towels. We add our token plate of biscuits to a table already mountained with sandwiches and scones, cakes and homemade tarts.

And then one of the daughters says, “I’ll take you up to Mamma.”

She ushers us down the long corridor, past small sitting rooms full of people, to the Best Room at the end — a kind of hierarchy of chambers.

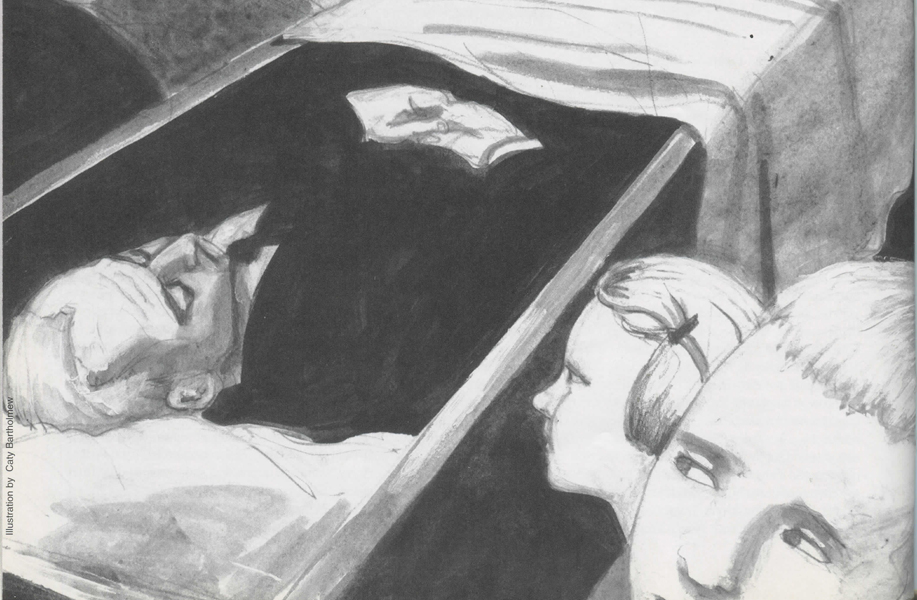

Mrs. Macklin (you must call me Mary) sits in a chair along the wall, with a line of women to each side. Joe lies in his tiny, tapered coffin on a table in the center of the room; candles at his feet and flowers by his head. Someone rises so that we, as the newest guests, can have a place to sit in the honored position next to Mary. This might be her husband’s wake, but it’s also the first time that we have been in her house. She concentrates on making us feel welcome.

Someone brings us drinks, wine for Joanne and Guinness for me, and we sit and talk as one would at any quiet party. Mary tells the history of the house (a former gate-house for the Crofton Estate nearby). She talks of colorful characters who have long since passed away, even of Joe himself. She refers to him as “my man here,” and his presence is included as if he were merely lost in his own thoughts and only temporarily distracted from the conversation.

It is breathtakingly honest. The family hasn’t shipped the body off to a funeral home. They’re taking care of their own. I look around the room at all the peaceful faces and admire their acceptance of what lies before them. Even the littlest grandchildren play quietly next to the coffin, and occasionally stop to look at their grandfather’s face. I envy them, for they seem to know, unquestioningly, some Truth that I have long ago forgotten. Suddenly I’m swept with waves of gratitude. What a loss it would have been if we’d given in to our petty insecurities and hadn’t come tonight! I vow to never again let fear get between me and the richness of life.

More people arrive, and we stand to let them take our place. Mary grasps our hands and smiles with genuine warmth. “I’m so happy that you’re here.” And we move on, to the other sitting rooms and the kitchen. Conversations pull us in, drink flows, and a sense of security settles down on everyone. There are no strangers anymore, no sense of separation. We’re all just…here…and we all feel somehow healed.

Though the hour is getting late, the house is crowded and people still arrive. Someone mentions that the priest will come at midnight to say the Rosary, and that some few people will remain awake all night to keep Joe company. But we feel it’s time for us to go. We thread our way through smiles and handshakes to the door and step out into the chill. As we walk home under the moon we know that though we went to offer our respects, we came away with much, much more.

Tomorrow night will be Joe’s removal to the church. Again everyone will gather at the crossroads. The house and yard will be packed with people, and of course there’s no question, this time, that we’ll go. It will probably run late. But eventually they’ll carry the coffin out of the house, and a long procession will follow the hearse, down past our house to the church in Athleague. The Mass will be given the next day, and then everybody but one will return to Macklin’s Cross for tea.

Next Day

So tonight was Joe’s Removal. It was set for seven o’clock, but by five-thirty cars were already thrumming by our house. Perhaps it was just the unusual rhythm of traffic, or maybe it’s because I knew where they were going, but it gave me a sense of — what? — mounting energy.

We were both trying to take quick naps before going up, but couldn’t sleep.

And of course it was raining again — a persistent mist with heavier drizzle at times. I stepped out the front gate and could see cars beginning to line the road up at the crossroads. Clusters of umbrellas were gathering like mushrooms on the corner.

So we drive up and park along the hedgerow. A neighbor had already told us that “you go in the front door this time, and as we approach the house we pass car after car with people sitting, waiting. They’d apparently already been in. Foggy windows roll down in turn. “Will, Joanne, hello, how are ye, dirty old evening isn’t it, ah sure but thanks be to God we’re here to see it.”

Just inside the door, the Best Room on the right, the receiving line starts. A large family standing in a long curving line, like an arm around the coffin. Shake hands with each, a murmured “so sorry thanks for coming.” They all look right into your eyes.

You know that soon the hearse will arrive, the entering guests will dwindle and the family will be left for a few minutes before the coffin is closed for good.

You pass out into the hall, past the sitting rooms now quiet, to the kitchen. Matrons whisper you’ll have some tea. Oh, thank you but I’m fine, really, thank you though. Out into the courtyard, and…one of them follows, steaming cup in hand, here’s your tea, do you take sugar? Pause, I like it just the way you make it, thank you.

And you wait in the cold mist. Waiting. Groups of people talking very quietly, shrugging against the rain. Waiting. At the corner near the front door a group of men collect. Some in dress coats, some in nylon jackets, all in black. They pass out armbands and help each other slip them on. White cotton, with hand-drawn magic-marker crosses; black.

Sometime when you weren’t looking the hearse slipped into place. Conversation stops and people stand silently as the coffin is carded from the house. The rain increases and we go to sit in the car. And then the hearse comes, slowly. It passes so close to us on the narrow lane that I could reach out and touch it. A blanket of flowers stretches the length of Joe’s coffin. “Daddy” it says.

We wait as the procession passes. Family first, steamed windows, then car after car after car. We pull out into a gap and join the line. You can see tail lights all the way ahead past our house to the curve at Gaffeys’. You can’t help but blink back tears, not so much for Joe but for the heartache of Everything.

All along the three-mile lane to Athleague the cars drive slowly. Someone coming the other way has pulled over and waits. It’s a long, snaking drive between hedgerows laced with dripping morning glories. No one is home in the old farm cottages along the route. Everyone is part of This.

As we enter Athleague, police have stopped traffic on the main road. They wave us through. Nothing will break the cord that coils in the churchyard until everyone is there.

Outside the open Gothic doors of the church the crowd grows, waiting in the rain. Joe will be the first to enter. The men with armbands open the hearse, slide his coffin out onto their shoulders and we follow it inside to share a prayer and wish him well for the night.

There will be no cars after the Mass at noon tomorrow. It’s a mile from the church, through town, to the graveyard on the hill, but everyone will walk with Joe. The men will take turns carrying him. The small grocery store will turn out its lights and lower its front door blinds. Everything will stop. Never mind that it’s the main route into Galway. People will stop, turn off their engines and wait. They too will bear witness. It’s what you do, betimes. ♦

Leave a Reply