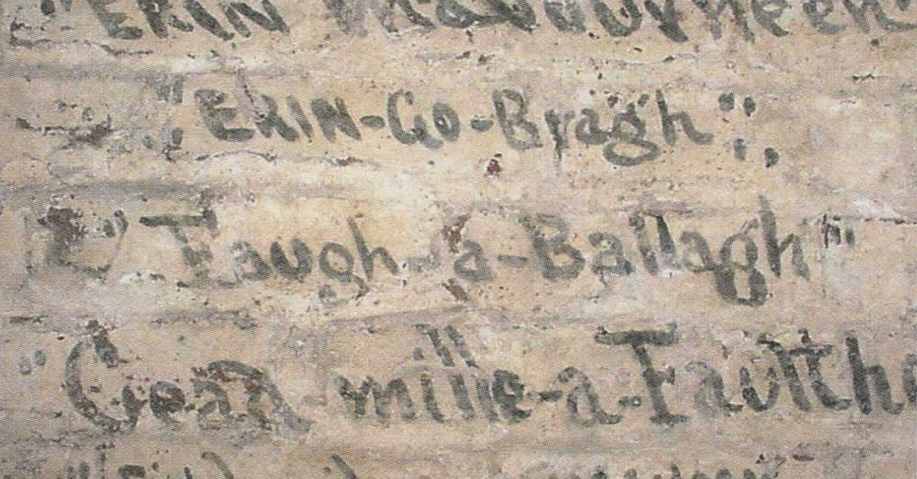

There’s a row of lead laundry sinks on the third floor of an old building on the Lower Manhattan waterfront where Irish women worked in the 19th century. And beyond the laundry drying racks, Gaelic graffiti appear in ghostly but bold script on the old brick walls. “Erin Go Bragh” is writ large. So is “Faugh a ballagh” (clear the way), a famous battle cry, perhaps recorded by a man on his way to fight with the famous Irish Brigade in the Civil War. Underneath some old wallboard, restoration workers found the drawing of a Gaelic harp.

The sinks and the graffiti are being preserved as part of the South Street Seaport Museum’s upcoming permanent exhibition, World Port New York. The hidden spaces and artifacts of the thriving businesses in the original 1812 Federal-style brick commercial buildings known as Schermerhorn Row at Fulton and South Streets will be visible to the public for the first time.

“There were several waves of Irish immigration. And in particular, women found their way into services,” said Peter Neill, president of the Seaport Museum. “Many came here until they got domestic service uptown. There’s not much evidence left of the role of women in downtown New York,” he said. The laundry in Schermerhorn Row is important evidence that will be preserved.

The laundry is in the part of the building that once housed the Fulton Ferry Hotel and Sloppy Louie’s Restaurant, both made famous in the 20th century by Joseph Mitchell’s New Yorker story “Up in the Old Hotel.” This part of the new museum will be left in its raw state with original chimneys, door frames, and decomposed wallpaper, allowing visitors to conjure the past. The upper floors had not been explored for decades, even while the restaurant was operating on the street level. As Mitchell implied in his story, nobody wanted to disturb the ghosts. When World Port New York opens in 2005, the ghosts will have some company.

World Port New York will span the port’s history from colonial times to the present and its role in the nation’s commercial, social and cultural development. The city’s economy was born on South Street. Known then as The Street of Ships, it was the place where immigrants got off the boat and found work.

It was the original world trade center, and the customs tariffs paid at the port were supplying more than half of the country’s income by the time of the Civil War. It was the first area of the city to receive electric light when Thomas Edison opened the world’s first power plant on nearby Pearl Street in 1822. The buildings of Schermerhorn Row were the mercantile high rises of their day. When demolition was threatened in the 1960s, a group of public-spirited people raised the money to buy the buildings and charter the museum in 1967. The following year, Schermerhorn Row was declared a landmark building in what is now the Seaport Historic District.

“This was the original vision, 37 years ago, of what our founders saw,” Neill said. “The vision was substantial enough to have been sustained,” he said of the restoration of Schermerhorn Row. “People are always asking, `Where’s the museum?'”

Despite a full-time staff of 39, a fleet of ships, 300 volunteers, and several small galleries on Water Street, the South Street Seaport Museum has never really had a gallery presence in the commercial shopping mall. Two-thirds of the new 30,000-square-foot gallery space is for the permanent exhibitions and one-third for changing exhibitions. The first of these, African Americans in the New World, opened in October 2003. Money for the restoration came from several foundations and businesses, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, and a building grant from the City of New York Economic Development Corporation.

“After 9/11 we lost half our funding from the Port Authority,” Neill said, explaining why progress was delayed two years, “but looking at the good side of that, it gave us more time to make sure the exhibitions are better.” The museum is rich in artifacts, but unlike the heirlooms of the great families collected in the uptown historical societies, this museum exhibition is about the working people downtown where it all began. It’s about preserving laundry sinks and graffiti on the walls.

There’s a certain irony in restoring New York’s original center of world trade that absorbed so many of the Irish people entering America. Now centuries and generations later, just blocks away, another World Trade Center site is being rebuilt and memorialized for the thousands of working people lost in the attack of September 11. Among those thousands of office workers, stockbrokers, police officers and firefighters, were descendants of those early immigrants who came to the new world through South Street. ♦

Leave a Reply