As Police Commissioner Ray Kelly rolls through the streets of Manhattan in the back seat of a black SUV he is fed a steady stream of information by his detail detective who rides shotgun. On this cold fall day there is the usual assortment of New York mayhem to report; a decomposed body has been found in a Queens park, a transit cop has twisted an ankle during a chase, a deranged man, wielding a knife and screaming about poor health care, has taken a nurse hostage at Jamaica Hospital, a traffic agent has collapsed, in Brooklyn a car dealership has received anti-Semitic hate mail laced with mysterious white powder. Kelly peppers the detective with questions, even cracks wise at some of the more absurd reports.

But one case clearly stands out. Earlier in the week an eight-year-old boy was shot dead, caught in a Brooklyn drug war crossfire while walking home from school with his father. Kelly receives constant updates as his detectives scour the back streets of East New York for the killers. The case bothers Kelly. First, it is an awful waste of young innocent life, but it is also an echo of an uglier time in New York, a time when Kelly was first appointed the head of the world’s largest police department.

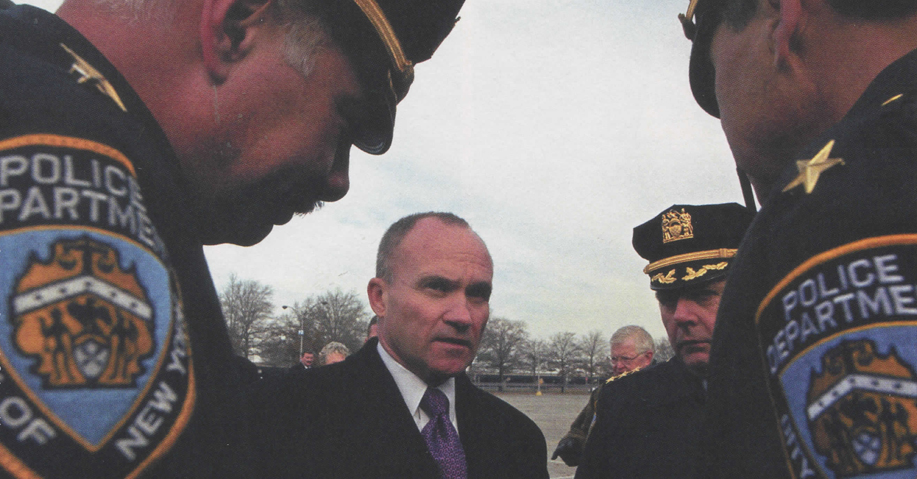

By 1992 it seemed the city had become unhinged. Mayor David Dinkins, besieged by a crack-cocaine-fueled epidemic of violence, was desperate to stem the bloodshed. So many bullets were flying that women in the worst precincts had taken to putting their children to sleep in bathtubs to protect them from flying lead. Headlines screamed “Dave Do Something.” In late 1992 Dinkins considered a short list of candidates for Police Commissioner. He chose Ray Kelly. In the complex world of New York’s tribal politics, the choice was not met with universal acclaim. Many in the African-American community believed that since the post had been held by two consecutive black commissioners, (Ben Ward, a career NYPD product and the first African-American to hold the job, and Lee Brown, a smooth-talking but seemingly ineffectual Houstonian) for the sake of race relations, another black should be picked. Dinkins says, “Colonel Kelly was simply the best qualified man for the job. Period.”

The new Commissioner’s résumé clearly backed Dinkins up. Kelly grew up on the then mean streets of Columbus Avenue when Irish-American gangsters like Poochie Walsh ruled the neighborhood. He recalls watching “scenes right out of West Side Story” unfold outside his apartment window. But the thug life was not for him. He enrolled in Manhattan College and joined the first police cadet class, a program aimed at grooming college graduates for careers with the NYPD. Kelly finished college and entered the Police Academy. But after only five days he was called by the Marines, who sent him to Vietnam to lead men in combat. It was not until three years later, with his obligation to the Marines fulfilled, that he returned to the Police Academy, eventually graduating first in his class.

Kelly hit the streets a newly minted cop, smart, ambitious, and eager to do well. But Ray Kelly lacked one usual criterion for success in the NYPD. He was the only one in his family to ever become a cop. There was no kindly uncle to grease the skids, no father or older brother to open the right doors, make a call, no “Rabbi” as they say in the NYPD. Ray Kelly had to make it on his own. And that he did. He eventually served in 25 different commands, slowly making his way up the ranks, surviving the department’s back alley politics that make the intrigues of the Vatican seem like a local Rosary society. At the same time he and his wife Veronica raised two boys, and Kelly earned a law degree from St. John’s, and masters degrees from both Harvard and NYU. Kelly was clearly a comer.

But he tells the story of his wife, the young bride of a new marine stationed in California who was asked on a bus why someone like her husband who had a college degree would want to pursue a career in law enforcement. She replied, “Someone has to be the Commissioner.”

The minute Kelly was appointed Commissioner, he aggressively attacked crime, putting cops where the bad guys were, and the numbers tell the story. During Kelly’s one full year as top cop (1993) there were nearly 30,000 fewer felonies committed in New York City than the year before. Kelly had turned the tide, and the long decline in violent crime began. “We had to look at the problem a new way. We needed to deploy resources where they would be most effective.” He also did something no one asked him to. After long days of fighting crime he would ride out to Bedford Stuyvesant, to Brownsville, and up to Harlem unannounced and alone, to speak at black churches and assure the congregations that his only aim was to make the city safer for everyone. Crime was dropping, race relations were slowly improving, and then Ray Kelly’s boss was voted out of office.

- Scott Fitzgerald fatuously declared that there were no second acts in American life, and while that maxim was proved untrue by everyone from Richard Nixon to Muhammad Ali to Rush Limbaugh, one place it was an absolute was in the NYPD. When Rudy Giuliani took office in January 1994, Ray Kelly’s storied run in the NYPD was history. I ask Kelly if he ever thought he would be back. His response is simply, “No. When you were gone, you were gone.” There was no reason to believe otherwise. In the 150-year history of the department, no Commissioner had ever been asked back. The PC is appointed by the Mayor, and most Mayors hire new faces for important posts, faces that owe their elevation and their loyalty to the Mayor. That’s politics. So, despite the fact that a historic drop in crime had begun, Kelly was shown the door.

Ray Kelly moved on. His successors and their boss did everything they could to downplay Kelly’s efforts. It was far better PR to claim those successes as their own. Kelly, while he could not have been happy, kept quiet. What no one could have guessed was that the most qualified Commissioner in the department’s history was embarking on an eight-year run that would make him even more qualified for a city and a world changed utterly on September 11, 2001.

When Michael Bloomberg was elected Mayor in 2002, he wasted no time in appointing the best man available for the job. The choice was easy. Ray Kelly.

We sit in Kelly’s office at One Police Plaza and I ask how the job had changed while he was gone. “In a word? Counterterrorism.” No longer was the job simply catching murderers and thieves and rapists. The bad guys are now much more dangerous. As if to illustrate this, Kelly is hosting an Interpol Counter Terrorism Conference at police headquarters.

We ride the elevator down and enter the auditorium. It is packed with all manner of attendees, spooks and flatfoots from forty-four countries, including Thailand, Angola, Qatar, and Uzbekistan. While Kelly was on forced hiatus from what he calls “the best job in the world,” he put together a police force in Haiti, served as the Commissioner of U.S. Customs, then head of law enforcement at the Treasury Department. All this serves him well today. He learned his way around the swamps of Washington bureaucracies, and was appointed to the executive board of Interpol, where he made worldwide connections to persons fighting terrorism. The street cop from New York is now seen as the premier law enforcement official in the world.

At the back of the room, translators wearing headphones huddle in booths. It looks more like the UN than Police Headquarters. Kelly welcomes everyone and then tells a story from the previous weekend, how a young transit cop witnessed what turned out to be two Iranian diplomats taking a videotape of a subway station at two in the morning. The men were apprehended and a Farsi-speaking officer was quickly summoned. This is the new NYPD. Kelly says, “Our cops are simply front line soldiers in the war on terrorism.” He stresses the need for communications amongst police agencies, for a proactive approach to fighting those “who want to do us harm.”

Kelly makes a point of introducing two of his Deputy Commissioners, Michael Sheehan and David Cohen. Sheenan, ex special forces, was the Department of State Ambassador at Large for Counter Terrorism who then went on to be Assistant Secretary General in the Department of Peacekeeping Operations at the UN. Cohen came to the NYPD from the CIA. They both point to Kelly as the main reason they agreed to switch to local law enforcement. Cohen says, “To work for Ray Kelly and help keep the most important city in the world safe? In 22 months, I have not questioned my decision once.”

Kelly has increased the number of Counterterrorism Joint Task Force detectives from 17 to 120 and in an unprecedented move, has stationed a number of NYPD detectives in foreign posts including Tel Aviv, London, Singapore, and Interpol headquarters in Lyon, France. Kelly knows that we can’t always count on the federal government, and that being merely reactive in fighting terrorism now means burying scores of your dead first.

After getting the conference started, Kelly jumps back in the SUV, and learns that two more culprits in the eight-year-old boy’s murder are in custody, two more to go. We head crosstown to the Chelsea piers and duck into a pavilion where eighteen cops are about to graduate and become new members of the NYPD’s mounted unit. We’ve stepped out of the world of dirty bombs, and radiation, and bioterror into the nineteenth century and the smell of horses and fresh dirt. Stiff backed cops in ceremonial dress mount their rides and put them through paces to the strains of martial music. The final number is “New York, New York,” and in a routine that would make Busby Berkeley proud, not a single horse missteps.

One by one, the graduates approach the stage and throw the Commissioner crisp salutes. Kelly hands out the diplomas, and then lingers to mingle. He obviously loves this ceremonial part of the job. It is a break from more serious duties, but also an important link to the past, a continuum. He understands the importance of these rituals, of the pomp, the circumstance. He was a street cop and he always will be. Cops approach him easily, and he clearly enjoys being among these men and women. You sense he does not want to leave. But his job does not permit much dallying.

We move onto a staff conference at police headquarters. The conference table is buffeted by the thick torsos of Kelly’s high command. These men — Borough Commanders and Deputy Commissioners — have all fought their way up the NYPD food chain. It is a biweekly meeting where they get to sit with their boss and hash out problems, strategies, and policy. Four television monitors play silently on the conference room wall speaking clearly of the new realities these men face. One is turned to NY1, one to Fox News, another to CNN and finally one to Al Jazeera.

Kelly, at 60, is the oldest man in the room, but that is hard to believe. His energy is unflagging; he is still Marine Corps fit. His style is smart, supportive. Everyone at the table knows what their job is. Kelly does not browbeat or bellow, but he does expect excellence. The topics range from Operation Impact, a successful targeting of high crime areas, to the upcoming Republican National Convention, to more mundane matters like parking for cops. Ray Kelly with the help of those assembled has quietly managed to keep crime in the city dropping steadily. He has done this with 4,000 less cops than his predecessor during a horrible economic climate and with the added burdens of picking up the slack for fighting terrorism.

Their business done, Kelly sees the brass out and gets ready for a press conference announcing the smashing of a Washington Heights drug ring. He and his aides iron out numbers arrested, kilos and cash confiscated. The operation was a great success and everything went off according to plan. In the volatile world of crime fighting, that is not always the case.

In early 2003 a narcotics squad executing a so-called no-knock warrant crashed through the door of a Harlem apartment. They were acting on a tip that armed drug dealers were behind the door. The tip was bad. What was behind the door was a 57-year-old grandmother named Alberta Spruill who toppled over and dropped dead. She was literally scared to death. Unlike the previous administration, the reaction was open and swift.

“Everybody makes mistakes.” Kelly says. “But, while in business a mistake might cost someone money, in what we do, it can cost lives.” Officers were quickly reassigned and there was a public airing of practices and policy. “We felt it was important to get the information out there and to somehow ease the pain of the family.”

The day is winding down and Kelly sits at his expanse of a hardwood desk. The desk was once occupied by Theodore Roosevelt, whom Kelly greatly admires. “He was a take-charge guy who lived life to the fullest.” Behind Kelly, his window overlooks the Brooklyn Bridge, alight and glorious in the falling dark. Beyond, the city stretches to the horizon as its citizens head home to family and warm dinners. In a world gone mad, Ray Kelly is responsible for watching over all of it, and all its varied inhabitants. The great Teddy Roosevelt, tough guy that he was, could not imagine the dangers that his successor, the milkman’s kid from Columbus Avenue, faces every day. Kelly is undaunted. “It’s still the best job in the world.” ♦

Leave a Reply