Irish women in the army from the Civil War to today.

℘℘℘

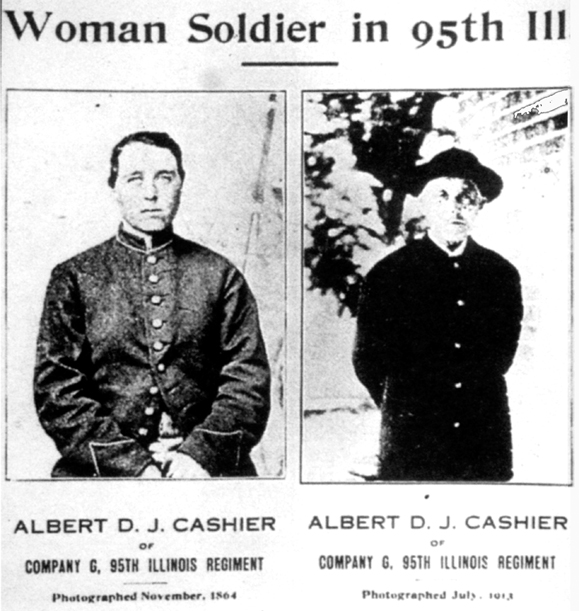

On May 18, 1863, Private Albert D. J. Cashier was among the many Union soldiers under General Ulysses S. Grant who took part in the infamous siege of Vicksburg. The Union army shelled the city relentlessly for weeks, and during the course of the battle Private Cashier, a member of the 95th Illinois Infantry, was actually captured While performing a reconnaissance mission.

In a dramatic twist, however, Private Cashier escaped by wrestling a gun away from a Confederate guard. Private Cashier was chased on foot, but then managed to make it back to safety.

Had Private Cashier been seized and interrogated, his captors might have discovered more than mere details about Union troop movements or General Grant’s tactics.

They just might have discovered that Private Albert Cashier was, in fact, a woman — an Irish immigrant named Jenny Hodgers.

At a time when the U.S. is again at war, and the dramatic escape and rescue of Irish-American soldier Private Jessica Lynch captured the hearts of people all across America, it is interesting to revisit the saga of Jenny Hodgers.

Many commentators noted that the Jessica Lynch story was all the more interesting because she was one of the many women who now make up the military’s ranks.

But controversy also surrounds the story of Jessica Lynch, with some people charging that her heroism was exaggerated amidst the ongoing war. Well, there could be no exaggerating the performance of Jenny Hodgers/Private Albert Cashier on the battlefield. She was one of thousands of Irish immigrants who fought valiantly in the Civil War. But she is believed to be the only one who did so disguised as a man.

Despite her many acts of bravery, Cashier emerged from the Civil War uninjured.

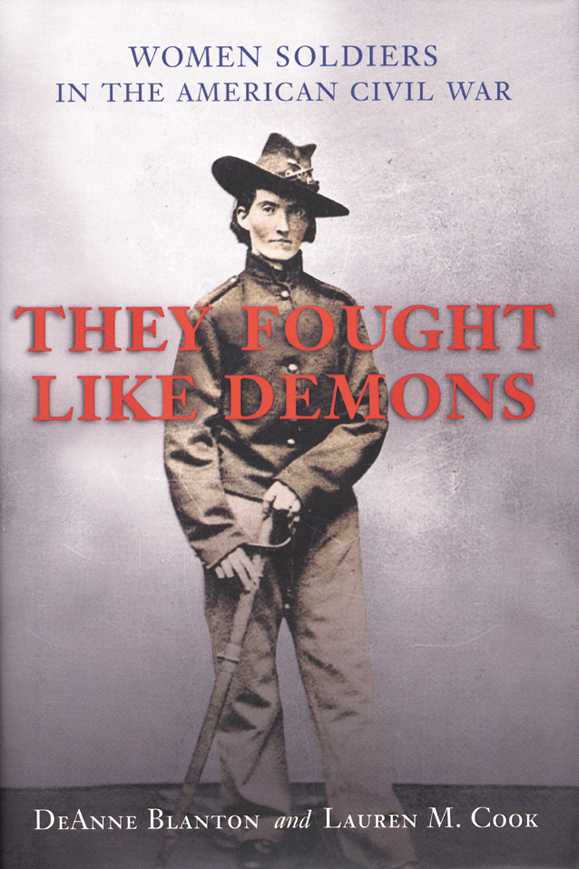

“She served a full enlistment, and long after the war, her fellow veterans remembered the diminutive Private with the Irish brogue as a good and brave soldier, and expressed a great deal of admiration for her heroic fighting,” according to DeAnne Blanton and Lauren M. Cook, authors of the recent book They Fought Like Demons: Women Soldiers in the American Civil War.

They continue: “Her compatriots marveled that despite her willingness to take on dangerous assignments, she was never injured or wounded. One of her fellow soldiers affirmed that Cashier was known throughout the regiment for bravery in combat. Another veteran remembered Cashier exposing herself to sniper fire by climbing a tall tree to attach the Union flag after it was shot down by the enemy.”

They Fought Like Demons describes more than 250 women who did just what Jenny Hodgers did: fought the Civil War disguised as men. The authors believe many more women were never detected.

But Hodgers’ story is particularly intriguing, not only because of her heroism, but because she had already been playing dual roles in her life, as an Irish immigrant who had relocated to America. In fact, authors Blanton and Cook believe her Irish background is one reason Hodgers was able to pass as a man undetected.

“With her light complexion, blue eyes, and auburn hair, she resembled the many other Irish Americans who served in the Union Army,” they write.

Not much can be verified about Jenny’s early life, in part because she had grown so accustomed to telling conflicting stories about her background. She continued living as a man until tragic circumstances marked her public exposure and death 50 years after the Civil War ended.

She claimed to have been born in Belfast around 1844, but one researcher also tracked down family in Clogherhead, County Louth. Hodgers may have been an illegitimate child and worked for her uncle, a shepherd. She also once said her mother later married a man named Cashier, and the family left for New York. (Others believe she was a stowaway.) Her stepfather is said to have dressed her up as a boy, called her Albert and got his “son” a job. When Hodgers’ mother died, she went west to Illinois where she worked as a shepherd, farmer and laborer — always as Albert Cashier.

In August of 1862, “he” enlisted in the army at Belvidere, Illinois.

At five feet, three inches tall, weighing 110 pounds, Hodgers was the shortest person in her regiment. She volunteered to be an infantryman, and her unit fought in 40 battles, the most important of which was Vicksburg.

How did Jenny do it? When she was inspected, authors Blanton and Cook say, members of her regiment simply had to show their hands and feet.

Nevertheless, in a military setting, soldiers eat, sleep, bathe and more right next to each other. It would seem there would have been many opportunities for Hodgers’ fellow soldiers to catch on, correct?

Not so, Blanton and Cook argue.

“Women soldiers who sought privacy to change clothes or bathe would not have aroused a great deal of suspicion, especially since they had already established reputations as modest men when they daily found private toilet areas,” they write. “Cashier was never discovered to be a woman while in the army, presumably in large part because soldiers spent the majority of their time outdoors with a wide latitude to seek privacy.”

Then, of course, there was the matter of looking like a man. Hodgers’ fellow soldiers even joked about her lack of facial hair. Yet that did not stop officers from describing her as “a short, wellbuilt man.”

But it was always a challenge for Hodgers to maintain her secret. In April of 1864, “Private Cashier” had to go into the hospital, complaining of diarrhea. Yet, it appears no doctor during the war ever discovered that Private Albert Cashier was, in fact, a woman.

Yes, on the one hand, it would seem that the doctors were not very thorough. But it’s also clear that Jenny Hodgers was a good actress, not to mention determined and very convincing. How convincing? It is believed she may have conducted some sort of affair, as Private Cashier, with another woman.

“Throughout the war Cashier corresponded with the Morey family of Babcock’s Grove, Illinois,” Blanton and Cook write. “Three of Morey’s letters to (Cashier) inquire about a `sweetheart,’ wondering if Albert had brought her a new dress. The Morey family, like the soldiers with whom Cashier served, did not know Cashier was a woman. Since Cashier’s letters to the Morey family have not been found, further information about the relationship…is unavailable.”

Nearly as sensational as Private Cashier’s war service are the circumstances around which this brave soldier’s secret was revealed.

The first person to discover Jenny’s secret was a town doctor in 1911. By then, “Albert Cashier” was doing odd jobs for Illinois State Senator Ira Lish, who accidentally ran over Cashier in his automobile. While tending to Cashier’s leg, the town doctor discovered Albert was in fact a woman. All involved, however, agreed to keep the matter a secret.

But Cashier’s leg never healed properly, and the State Senator arranged a spot in a rest home for (male) veterans. For three years, all staff knew of Private Cashier’s secret, but did not reveal it.

Cashier’s mental and physical health declined, and she was about to be declared insane by the state. Little did they know, as the newspapers were about to report thanks to an unknown tipster, that this supposedly insane man had a startling secret.

While the State of Illinois talked endlessly about this fascinating story, there was a more banal fact to contend with: Was this Jenny Hodgers actually a person who had defrauded the government in order to receive compensation as a Civil War veteran? An investigation was launched. But it was Jenny’s former comrades from the 95th Illinois Infantry who rallied around her. They testified that this was once the small yet brave soldier who routinely performed dangerous missions.

As one observer has written: “No mere matter of sexual identity could efface the valor and fellowship of their comrade Albert Cashier, who had stood in the ranks as a fighting member of the Union Army.”

But there is also a much more sad and tragic element to Jenny Hodgers’ final days. True, her comrades spoke well of her, and she was granted veteran status after all. But she was still sent off to an institution. Not only that, she was now forced to wear female clothing. This had “tragic consequences,” Blanton and Cook write.

“She was a frail 74-year-old who did not know how to walk in such apparel, having worn pants her entire adult life and probably for a good part of her childhood as well. Cashier tripped, fell, and broke her hip. She never recovered from this injury, and spent the rest of her life mostly confined to her bed.”

On October 10, 1915. Albert D.J. Cashier died at the Watertown State Hospital.

Jenny Hodgers was buried with full military honors in Sunnyslope Cemetery with a marker reading: “Albert D. J. Cashier, Co. G, 95 Ill. Inf.”

Hodgers is also honored on the Illinois memorial at Vicksburg with the inscription, “Cashier, Albert D. J., Pvt.”

Roughly 60 years after her death, another headstone was erected next to Private Cashier’s grave marker. It reads “Jenny Hodgers.” ♦

I’m looking for information of my great grandmother Hanora Donlon, Galway Ireland Lough Park b1842 immigrated to US to work in the civil war. (After she returned to Glenamaddy, Galway Ireland)