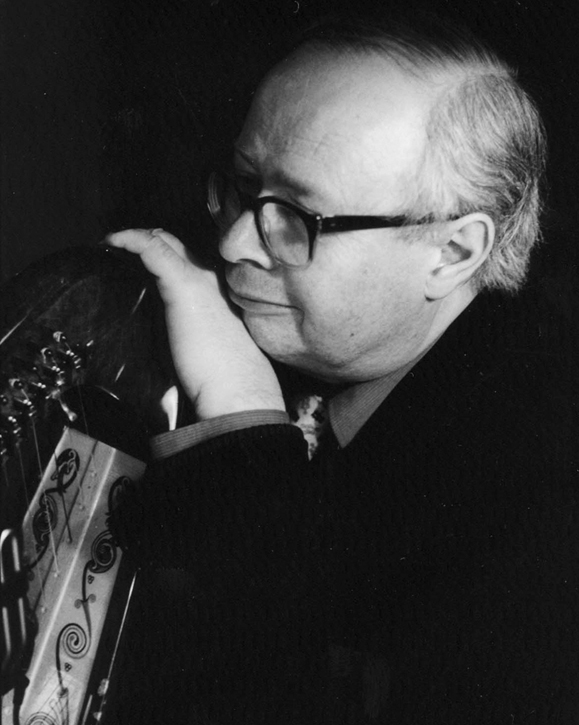

Paddy Moloney, founder of The Chieftains, who has done more than anyone else to launch Irish music onto the world stage, talks to Lauren Byrne.

In the expensive gloom of Boston’s Copley Plaza Hotel, Paddy Moloney orders a pot of Earl Grey tea and shifts out of the draft from an over efficient air-conditioner. At 65, his hair is dappled gray, but Moloney’s bantam figure is as trim as ever; and a sore throat at the start of The Chieftains’ annual U.S. summer tour is not enough to stop him talking. Next to playing music, he freely admits, he loves to talk.

We might be forgiven for thinking that this uilleann piper with six Grammys, several BBC Lifetime Achievement Awards and an honorary doctorate from Trinity College, Dublin, is ready to slow down a bit. But conversation with Moloney, in whom affability, creativity and fearless curiosity combine in gargantuan proportions, suggests quite the contrary.

“I’ll go out with the boots on,” he says with cheerful disregard for his aching throat as he launches into such topics as his improbable liaisons with rock legends, his current adventures in Nashville, and the legacy he has initiated to commemorate his late friend, and former Chieftains harpist Derek Bell, who died last year.

These days Moloney and the rest of The Chieftains, Matt Molloy, Kevin Conneff and Sean Keane, spend four months of the year touring; much of that time is spent in the East, where ever younger audiences are flocking to see them in places like Malaysia and Singapore.

At home in Glendalough, Co. Wicklow, when he’s not on tour, Moloney is hardly less busy. Since The Chieftains played on the soundtrack for Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon in 1977, Moloney has either scored the music or contributed to soundtracks for numerous movies including Far and Away with Nicole Kidman and Tom Cruise, a movie its director Ron Howard says was actually inspired by The Chieftains’ music. Most symptomatic of how ubiquitous Moloney has made Irish music is his soundtrack for Disney’s Winnie the Pooh movie (based on the A.A. Milne characters that are the very quintessence of English culture), which earned Moloney a Grammy nomination in 1996.

“I never stop,” he admits. “Every day there’s something new. People say how do you do it? Maybe I have some Godgiven gift. I just see the big picture.”

Moloney not only sees the big picture, he has been at the center of the big picture since at least 1975, the year The Chieftains made the crossover from folk music venues to their first sold-out concert at London’s Albert Hall. While good friends Mick Jagger and the Stones only got around to organizing a concert in China this year (cancelled because of the SARS epidemic), The Chieftains played on China’s Great Wall as long ago as 1983. On December 8, 1980, the day John Lennon was shot, Moloney was in a London recording studio with Paul McCartney. In 2002, Moloney played a special piece on his tin whistle for the rescue workers at Ground Zero. In the forty-odd years of The Chieftains’ career, Paddy, the only remaining original member of the band, has played, twice, at 4th of July concerts in Washington before hundreds of thousands. He’s also performed with lone flute players in the jungles of Bali and accompanied singers in the remote Japanese-controlled island of Okinawa; in the process arriving at something close to a theory that suggests there are only a limited number of tunes in the world, the only distinction is in the way each culture expresses them. Increasingly in demand to talk about his findings, and forgetting that it takes someone touched by genius to spot these connections, Paddy makes it all sound so easy.

“Rather than read books as musicologists and others do,” he says, “I just go there and sit down with the people and play.” His eyes glint with mischief at the memory of one such field survey closer to home.

“A few years ago I was in a restaurant in New York with my wife, Rita, where they had a Brazilian band playing. I decided, what the hell — I had me tin whistle with me — so I got up to play with them. I was busking away with this Brazilian music for about twenty minutes. Then I jumped off the stage onto a chair like a grasshopper, and Rita said, `Don’t you ever do that again!’ Ah she knows me well,” he chuckles, “after 40 years of marriage.”

“He’s a wonderful daddy,” says his daughter Aedín, an actress who starred with Ewan McGregor, in the movie Nora, on Mrs. James Joyce, and whom New York audiences know from her regular stage appearances with the Irish Repertory Theater. “But it’s hard to follow a musical genius,” she adds. Like older brother Aonghus an archaeologist who now teaches underprivileged kids, and younger brother Pádraig, a NASA space engineer, she chose her own field.

Paddy Moloney is not just a musical genius, he is a brilliant arranger. His most commercially successful marriage of styles and sounds was in 1994 on the Grammy-winning The Long Black Veil, the album that partnered Chieftains’ music with a bevy of enticingly unlikely interpreters. On it, rock icons Mick Jagger, singing the title song, and Sting, who gives a haunting rendition of Mo Ghile Mear, are joined by the likes of Marianne Faithfull, Ry Cooder, and Tom Jones.

As any Chieftains concert attests, Paddy has the ability to re-create the intimate atmosphere of the kind of all-night ceilis that were part of his childhood, when the Dublin-born Moloney spent the summers with his musical grandparents deep in the Slieve Bloom mountains. So it’s easy to imagine even the po-faced Sting loosening up in a session with Paddy in the recording studio. Indeed, as John Glatt’s 1997 biography of The Chieftains reveals, Moloney has always been something of a superstar’s superstar.

“I remember going to the late Brian Jones’ flat in 1966,” he says, “and Peter Sellars was there and Mick Jagger, and they were playing The Chieftains. I couldn’t believe it. There was a very limited market at that time for Irish music, but they loved the sound, and the idea of going back to the source of music.

“I was always very proud of Irish music. I wasn’t going to be bought out or taken over. You either liked it or you didn’t. With me the music came first.” In hindsight, this non sequitur in the context sounds like Moloney’s reflexive rebuttal to his critics who accused him of sullying Irish music by his too-free liaisons with the glitterati of rock.

Moloney’s first invitation to contribute input to non-traditional music came in 1972, when Paul McCartney asked him to add some pipes to an album his brother, Mike McGear, was making with his band, The Scaffold. Soon the likes of Mike Oldfield, Don Henley of The Eagles, and Mick Jagger were lining up with similar requests.

“I don’t think there’s any limits to Irish music. You can play it so many ways,” he explains. “I put on a music festival in London in 1991 and The Who’s Roger Daltry sang “Carrickfergus.” It was the first time he could use his voice properly without having to belt it out with The Who. Then we recorded An Irish Evening with him, which won a Grammy too.

“I’ve been asked to record with big names.” He mentions a request he’s just received from Jerry Lee Lewis, which he’s happy to accede to, but adds, “I’ve often turned things down for the simple reason I didn’t think it would work.”

More recently, Moloney has turned his attention to Nashville and the more obvious connections between Irish music and American country music. This “bluegrass/green grass connection,” as he calls it, has produced a new crop of memorable liaisons. On the first of two albums entitled Down the Old Plank Road: The Nashville Sessions, such legendary names as Earl Scruggs, Ricky Skaggs, and John Hiatt, among them, mix Irish melodies with bluegrass songs.

An accompanying DVD of the Chieftains in concert with many of the same performers at the historic Ryman Auditorium in Nashville features performances from longtime friend Emmylou Harris and relative newcomer Alison Krauss, while backstage, even the most seasoned bluegrass performers gush about what a thrill it is to work with The Chieftains.

“Down the Old Plank Road says something about the talent and the diversity of Paddy and the band,” Ricky Skaggs comments, referring to the seamless meshing of Chieftains music with bluegrass. As arranged by Paddy, songs that Skaggs has known since childhood reveal their Irish origins.

For his longtime friend Emmylou Harris, Paddy reversed the process. Choosing the old Irish ballad “Lambs on the Green Hills” for her to sing, he gave it a country feel. “It’s always a pleasure to hang with Paddy and The Chieftains and make a little music,” she says.

Intended as a single CD, Paddy ended up recording enough material for two (part two is due out in September). Songwriter/musician Tim O’Brien explains the alacrity with which the bluegrass community responded to Paddy’s invitation to make music. “There’s a joke in the traditional music world: Why did the chicken cross the road and the answer is, to record with The Chieftains.”

The DVD is a collector’s item for another reason too: it captures the last performance of Derek Bell, the classically trained harpist who joined The Chieftains in 1972, and whose sudden death on October 17, 2002, stunned everybody. Several times Paddy mentions Bell. Talking about Bell is his way of keeping his great friend around, he says. As our conversation comes to a close, Paddy elaborates on the depth of his loss.

“I miss old Ding-Dong. He was a great character. He was the one I poured out all my troubles to.”

After a minor operation on his prostate in Phoenix, Arizona, Bell was given the all clear but died shortly after the Ryman Auditorium concert.

“I tried to get him off the milk and sugar. I came downstairs in our hotel the morning after the concert and there he was with the sugar. `You so-and-so,’ I said, `you’re not supposed to be eating that.’ `It’s all right, Doctor,’ he said. (He called me that because of my honorary doctorate from Trinity). `It’s all right, Doctor, it’s brown sugar.'”

In memory of Bell, Moloney has established The Chieftains/Derek Bell Scholarship in Limerick University to support young musicians from around the world who want to study Irish music. For a number of years now, Moloney has been increasingly involved in supporting the next generation of traditional musicians. To this year’s tour line-up he added Caroline Lavelle, a young cellist from Cornwall, and Jon and Nathan Polatzke, a couple of Canadian boys who perform a mesmerizing variation of Irish step dancing.

“So, if there’s anybody out there reading Irish America magazine,” says Paddy, not one to miss an opportunity, “who’s interested in supporting the scholarship fund, they can contact the Irish World Center at Limerick University.”

Earlier this year, Moloney brought together old friends Van Morrison, The Dubliners’ Ronnie Drew and others to join The Chieftains for two memorial concerts, one in Dublin, the other in Belfast, the proceeds of which went to fund the scholarship.

“They were some of the best concerts we ever had. I think Derek was up there with a big stick making sure I did it properly.” ♦

Leave a Reply