Floating Museum Shows Irish-Americans What Ancestors Encountered.

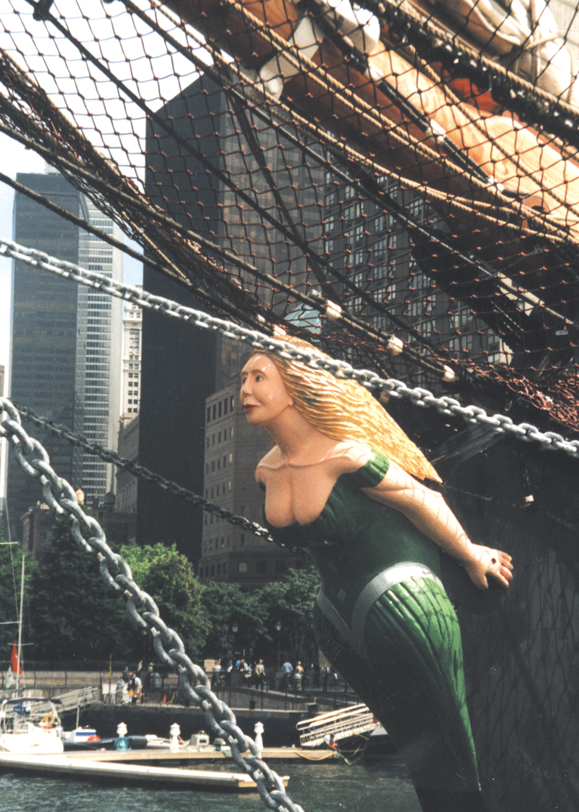

In 1848 it would cost you $5.50 to cross the Atlantic from Ireland on the sailing ship Jeanie Johnston. That fare represented half a year’s wages for an Irish laborer hoping to start a new life in America. Today, for $7.00 you can buy a ticket to visit the Jeanie Johnston replica, a floating museum, while it tours the east coast of North America. Below deck you can try to imagine what that two-month voyage in steerage was like for the 200 or more passengers. Entire families — or strangers — squeezed into bunks together or took turns sleeping. There were few comforts and no toilets. But sometimes there was a fiddler to brighten the darkness.

In making the journey to North America, the crew of the $15 million Jeanie Johnston replica has recreated the trip that more than two million Irish emigrants braved during the Great Famine that swept through Ireland in the mid-19th century. More than 2,500 of them came to the United States and Canada on the Jeanie Johnston between 1848 and 1855. And thanks to a caring captain and the ship’s doctor, there was never a loss of life onboard despite sickness and childbirth.

The original Jeanie Johnston was built in Quebec in 1847 and made her first voyage from Blennerville, near Tralee in 1848. After carrying the Irish to America, the ship returned to cargo service and in 1858 sunk after the crew was rescued. The replica was built at Blennerville by an international team of young people from Ireland (north and south), the United States, and Canada. They were supervised by shipwrights through FAS, the Irish training and employment agency.

The 2003 crossing took two months, about the same amount of time it took in the mid-19th century, when a transatlantic crossing was highly unpredictable and dangerous for the weary and malnourished Irish. Then, the crew had to steer with aid of a magnetic compass and two men were needed to hold the wheel in bad weather. A century and a half later, the weather can still be bad, but the new ship is safer with a steel hull and a modern navigation system.

“We left Ireland and sailed right into a 50-knot gale,” said First Mate Rob Matthews, a Brit and professional mariner for 29 years. “Then three days later we were in another one.” Most of the sail trainees were sick, according to Captain Tom McCarthy, who was in the Irish merchant navy, and who, like the original Jeanie Johnston captain, James Attridge, hails from Cork. Matthews said, “Some of these people have never been to sea in their life.” Laughing, he added, “And some may never go again.”

In addition to 15 professional crew, the 40 people on board included volunteer crew, and trainees. Half the trainees were disadvantaged Irish young people from 19 to 29, supported by the International Fund for Ireland (IFI).

“They were both Catholic and Protestant and they all got on just fine,” said Matthews, who believes in the importance of sail training. “You get some scruffy street kid from Belfast who never had a lesson in anything. For the first time he realizes there’s a reason for things. You have to pull that rope at a certain time because it needs to be done.”

The other trainees were older and paid as much as $3,500 to make the crossing. (The April-May Irish America has the story of 81-year-old crew member Tom Kindre.) The professional crew also included four women. Ironically, the Jeanie Johnston carded more young single women to America than any other emigrant ship. Listed on the passenger manifest as “spinster,” many between the ages of 16 and 30 found work as domestics in America.

It’s a Voyage into the Unknown

“Up aloft, that’s our engines,” said Captain McCarthy, who has been a professional mariner since he was 17. Safety is the captain’s first concern. “You never know what’s going to happen on a new ship,” he said. “It’s a voyage into the unknown.” McCarthy described the Jeanie Johnston as “a heavy ship. It sails like a tank.” He said he doesn’t send kids up in the rigging in a bad storm. He had no real accidents except for a couple of broken ribs perhaps.

Now 50, the personable McCarthy considers this work a young man’s game. “You have to be young and fearless.” Nevertheless, he keeps his hand in the game and was happy to be invited to head up the Jeanie Johnston crossing and American tour. “It was a great honor,” he said. He’s been master of six of these tall ships. When he’s not at sea, McCarthy works with his wife Breda in her furniture business.

In working her way up the east coast from Florida to Newfoundland, the Jeanie Johnston’s largest public turnout as of mid-July was in Port Jefferson on Long Island where 3,400 people came aboard in a single day. During her five-hour sail there from New York City she was accompanied through Long Island Sound by many private boats, some with bagpipers blowing a tune into the night air. Previously, Bristol, a small Pennsylvania town on the Delaware River had the biggest turnout.

“We tied up at the dock which was at the end of the main street,” said Captain McCarthy. “During the four days, 9,000 visitors turned out.” The ship and crew were greeted by brass bands, a church mass, and picnics with town residents.

Captain McCarthy would like to see the Jeanie Johnston continue as a training ship. “You need a subsidy,” he said when asked about the ship’s future. “If we get good PR in America, we’ll return to Ireland with a successful image. Otherwise,” he said, “there’s no future for her.” He would like to see an Irish and American effort to keep it going as a sail training vessel. ♦

Leave a Reply