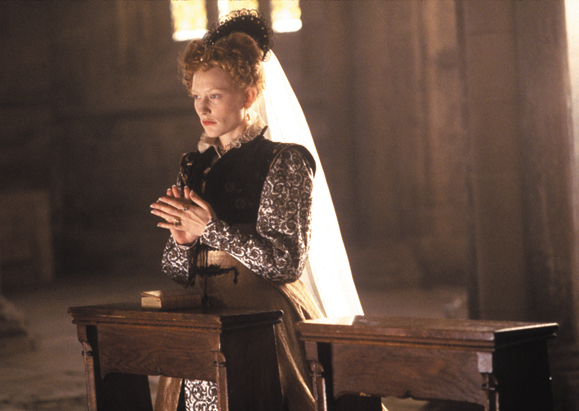

An acclaimed Australian actress known for tackling tough parts, Cate Blanchett takes on her first Irish role in Veronica Guerin. Smart, provocative and down-to-earth, Blanchett spoke to Louise Carroll just before the movie’s U.S. release.

℘℘℘

Cate Blanchett has played a range of characters in her career including the Queen of England, the elf queen Galadriel of Lothlorian, an American housewife, and now, an Irish journalist. She has starred in The Gift, The Lord of the Rings, Charlotte Gray, and Pushing Tin. She was nominated in 1998 for an Best Actress Oscar for her performance in the title role in Elizabeth. At 33 years old, she is in the prime of her career and her life. She is married to Australian screenwriter Andrew Upton and they have a two-year-old son, Dashiell. Blanchett discusses the challenges of playing Veronica Guerin, an Irish crime journalist who was murdered in 1996 by drug dealers who wanted to put a stop to her work investigating them and the Dublin criminal underworld.

Louise Carroll: How were you first approached about the story of Veronica Guerin?

Cate Blanchett: I had always wanted to work with Joel Schumacher, the director of Veronica Guerin. He was one of the first people I met when I went to L.A. for the first time in 1998 when I was doing Oscar and Lucinda. Through my agent I was sent the 60 Minutes tape about Veronica Guerin. I was intrigued by watching her speak and the way she spoke and the circumstances under which she worked. That was before there was a script, and I had never read an article that she had written. The great irony is that I knew her because she died and I didn’t know her as a living, breathing figure.

What was it like working and living in Ireland?

I just had a little baby who was nine or ten weeks old when we started to shoot, so it wasn’t really a time to travel, but we did go to Galway at Easter time. I had five days off and we went out to Galway, which is just gorgeous.

It’s a very strange experience working in another country, because on one hand you’re incredibly privileged because you’re not a tourist at all, and particularly with a film like Veronica Guerin you’re going straight to the heart of a really Dublin subject. So I was speaking to T.D.s [members of parliament] and family members and going through the newspapers. You’re going to the heart of something that a tourist can’t, but you’re in such a beautiful place. And you don’t get to have the simple joys of visiting because you’re working. It’s a very different mindset.

What was it like working with a completely Irish cast and crew?

Strangely enough, Veronica Guerin felt like making an Australian film, in that we work with relatively small budgets and there’s an ethos among the cast and crew in Australia that’s not hierarchical. Everyone just mucks in and gets on with it. The atmosphere on set in Ireland felt incredibly familiar to me. The crew was fantastic. There was a buoyancy to it, and Joel Schumacher fit right in. He is such a fabulous raconteur, and he fed the buoyancy on set. There were a lot of laughs on set, which was great because the subject matter was really intense.

How would you fit the film into the grander scheme of your career?

Having just had a child, there was a sense of get out and do it. I was quite nervous because it was the first time I’d gone back to work as a new parent and negotiating all that stuff and wondering how it would all go. Trying to get back and put Dashiell to bed was a major focus of my day. I just had to trust that I had done my homework and that I was 100 percent focused when I was working. But every job has its own challenge or problem. The initial one is always the matter of the accent and finding your way into the character. There is a particular responsibility that one has in playing a character who has lived and died so recently. She existed in the media and there’s a strong sense that she has been claimed by the Dublin public. People know what she looks like, what she sounds like, what she represented, and they know what she did. So they are either going to believe me or not. I just had to make sure that I had the accent right to start with!

What was your reaction to the script?

I first read the script in 2001. The script is a very organic beast. When someone has had such a short, sharp, extraordinary life as she did, you could tell a thousand different stories about her. Joel had to settle on what the angle was going to be. There was some of that in the original script. And as actors, directors and writers you go out and do your research and [you listen to] some of the extraordinary things that people tell you. Soaking up the atmosphere of actually being there adds to it. Then the script changes and expands. That’s part of my job, to bring the details that interest me into the script. Like the little anecdotes that Jimmy [Veronica’s brother] would tell me, they all go into fleshing out the character. I’m presenting a three-dimensional human being. Her celebrity status rose in the last years of her life. When someone is cut off in her prime, the iconography of that takes over and the person can get left behind a little bit. It’s a matter of me fleshing out and inventing, in a strange way, the human being behind the façade.

Wasn’t it hard to play a woman who so many knew so well?

I quite like hard things. I often like things that other people think are difficult, because I like a challenge. If something seems too easy I don’t necessarily see the reason for doing it.

Were you worried about meeting the expectations of the Irish public and Guerin’s family?

Of course that’s something you think about when you go into it. To be honest, I thought of that when I played Galadriel [in Lord of the Rings] or Elizabeth or Charlotte Gray. Because when you play a character from a well-loved novel, you hope that you’re going to be the quintessential person from that novel; but you may not be for some people. That feeling exists very often. I think I pushed it [the expectations] far out of my consciousness, or else I would have been a mess of nerves and I wouldn’t have been able to work.

But I’ve never been more nervous than the opening night of Veronica Guerin in Dublin. Having the opening in Dublin was so right because the story originated there and in a way it’s owned by those people who were there: her family, friends, colleagues and her readers. That was really nerve-racking for me because I suddenly thought, “I’m an actress in a film and these people knew this woman.” It was almost like her memorial service.

What gave you satisfaction in watching the finished film?

When I watch a completed film, I always have to cover my face with my hands just in case something dreadful comes up, and I always sit at the back! The best thing for me was that before I saw it, Joel had shown it to Bernadette Guerin [Veronica’s mother] and some members of the family and she gave it the thumbs up. She was really pleased. She felt like I had done it justice, and I breathed a huge sigh of relief. I knew that my Irish accent must be alright! I know I don’t look like Veronica, and of course you try to look as much as you can like the person, but that is not the point. The point is that the audience, and hopefully her family, has to believe that you are that person for the hour and a half. That you have captured the spirit of the person. And that’s a much more ephemeral thing to do. I was really relieved. And I thought, “OK, now it’s just a matter of whether people like the film or not.”

Did you relate to Veronica Guerin because you are both married mothers who are famous and in their thirties?

You always try to find the things that you can relate to in a character. I was really unsure about having a young baby and going back to work and that pull that you feel because whenever you leave your child you miss them so terribly. And my husband said to me, “Veronica had the same pull, so just accept it.” But that was the only thing. I don’t like to think too much about myself when I’m working. So I look more for the differences, not the similarities.

Do you use method acting?

I use whatever works. That’s the great thing for me having gone to a drama school. You use technique when you need to solve a problem and it’s a great thing to fall back on. It’s like a dictionary. And you don’t think about your technique. I’ve been doing it for a while now and you get used to the process of it, and ultimately, it’s about your instincts. If a scene is not working, then I will use any technique that will work to realize that moment.

Would you say you share Veronica’s attitude about doing something of worth in your career?

Yes. What I admired her for is that when she saw a major problem, it wasn’t in her nature to dance around it. She went up to it and dealt with it. It’s that idea that if you can understand a problem, then you can solve it. When you start a new role as an actress, you think, “I can’t possibly do this. I have no idea how to do this.” Part of playing a character is to understand a different way of thinking and you go into something head on. You have to be fearless in your work. But she and I had very different jobs. I could never have done that doorstepping stuff she did. I’m in awe of that kind of fearlessness.

What’s your opinion about her employers at the newspaper not having done enough to protect her?

I think it’s a very complicated thing that we all have in the wisdom of hindsight. A moral and political judgement is so much easier for those who don’t participate, who are on the sidelines of it. She was a really passionate person who was at the center of life. She didn’t have a desk at the Sunday Independent, she was a lone wolf operating on her own terms.

She was taking John Gilligan to court. [Gilligan is a Dublin crime boss believed to be responsible for her murder. Guerin had doorstepped him and he viciously assaulted her less than a year before she was killed]. There was no coordinated approach from the Gardai, the revenue commissioners, and the government to prosecute these guys for what they should have been prosecuted for, which was drug dealing. To put Gilligan away and to prevent him from attacking and threatening her or anyone else, [she had to] get him on assault, which is what she was going to do. In the film — the Sunday Independent — I mean who knows what went on at the time, but in the film, the Sunday Independent asked her, Do you want to write a story about it [her attack] or do you want to prosecute him? And she chose to prosecute him, although he got let off.

It would be a great thing if she were still alive. Maybe if she hadn’t been Veronica, she would still be alive. I think it was partly in her nature and partly, until she died, that everyone including herself underestimated the danger she was in. Because these guys made threats to everyone. The Irish crime journalist Paul Williams was threatened when we were in Dublin last month. It’s an ongoing thing. I also think that she believed she was doing something important and she didn’t want to be bullied.

Would you consider the film a Hollywood thriller or an Irish biopic?

I think no matter the size of your character, or the name of your character, the story is always a biopic of your character because you have to look at it through your character’s eyes. But objectively, I don’t think of it as a biopic at all. I don’t see Elizabeth or Charlotte Gray as biopics. They’re always about a character in a set of circumstances, and it was the circumstances that interested me as much as Veronica.

I think the film is unique in that watching the film feels like a car crash. You know at the beginning that this car is crashing and then for the next hour and a half you watch it crashing and you know you’re powerless to stop it. I don’t invest in genres, except as a reference point. A good film these days tries to find its own niche. So I always saw it as being a dance of death between Gilligan and Veronica.

It’s unusual for a movie about Ireland to be from Hollywood and aimed at a mass audience.

I think that it’s a mistake that people make to think they can find a mass audience that everything appeals to. There is no such audience. I think that if you make a film that has a weight behind it like Jerry Bruckheimer [the producer] — he really fascinated me about the whole thing. This is a departure for him, and there’s a female lead and I think that’s fantastic! If Jerry’s behind it, then hopefully it will find an audience. The film has to be interesting. One of the things I did like about it is that it wasn’t about the IRA, and yet it was a film coming out of Ireland with a really Irish subject. Like all great stories, they translate across cultures. Journalists are dying, globally, everywhere, and this movie feels strangely timely.

Is there a responsibility that the media should shoulder in making heroes of characters who fight crime like Veronica Guerin as opposed to making heroes of criminals, such as The Sopranos?

I must admit it’s not something that I thought about. But quite a few people who’ve seen the film have said to me that they’re really pleased that the criminals are as sleazy as they actually are, as opposed to making heroes of them. The interesting thing to me is people criticizing Guerin and saying, “How could she, as a mother, do what she did?” I think that we live in quite cowardly times when anyone who has idealism and is prepared to fight for it is considered foolhardy. Most heroes who we see are people who get away with things or gangsters, or they have a lot of money, and it’s not about a sense of idealism. And that’s what I found quite inspiring about what the film was dealing with.

But I think you need to educate people to read images. The role of art is to inspire and to allow people to fantasize. It’s not about moralizing and ethics. That should hopefully be instilled at home, school and whatever your church is.

I also wanted you to know that you’re the first non-Irish person on the cover of our magazine.

How exciting, I’m the first non-Irish person on the cover of Irish America? Fantastic. So the next time I go to Dublin, if I can’t get into a restaurant, I’ll just pull out the issue of the magazine with my picture on the cover! ♦

Leave a Reply