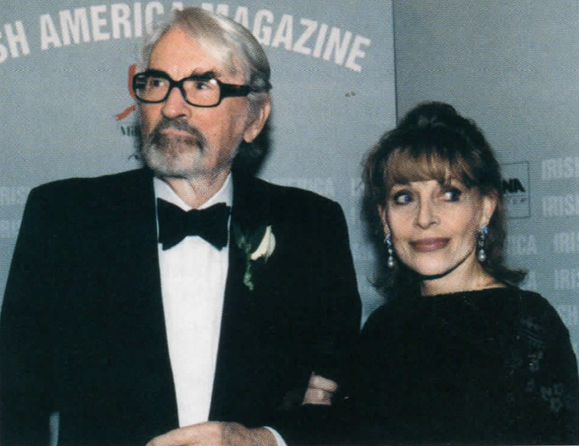

In June 1997, Peck, who rarely gave interviews in his last years, sat down with Irish America Editor Patricia Harty. An edited version of that interview follows.

“Will you pour?” The gentleman sitting across from me cracked a smile as I nodded and lifted the teapot, wondering if I would be able to complete the task without making a fool of myself. I felt as if I was in a scene in one of those Sunday matinee movies of years ago. “Try those pastries, they’re Lebanese. A professor friend of mine sent them over.”

Gregory Peck was doing his best to put me at ease. Not an easy job. After two weeks of watching some of his most memorable roles – as the dashingly handsome journalist Joe Bradley, who wins Audrey Hepburn’s heart in Roman Holiday, the cowboy, Jimmy Ringo, in The Gunfighter, the fighter pilot, General Frank Savage, in 12 O’Clock High, the missionary priest, Father Francis Chisholm, in Keys of the Kingdom, the commando, Captain Keith Mallory, in The Guns of Navarone – I was more than a little starstruck, but delighted to be spending an afternoon at the actor’s home in Beverly Hills. And once again I’m thankful for the strong pull that Americans have for their Irish heritage, the reason that Peck, who rarely gave interviews, agreed to this one.

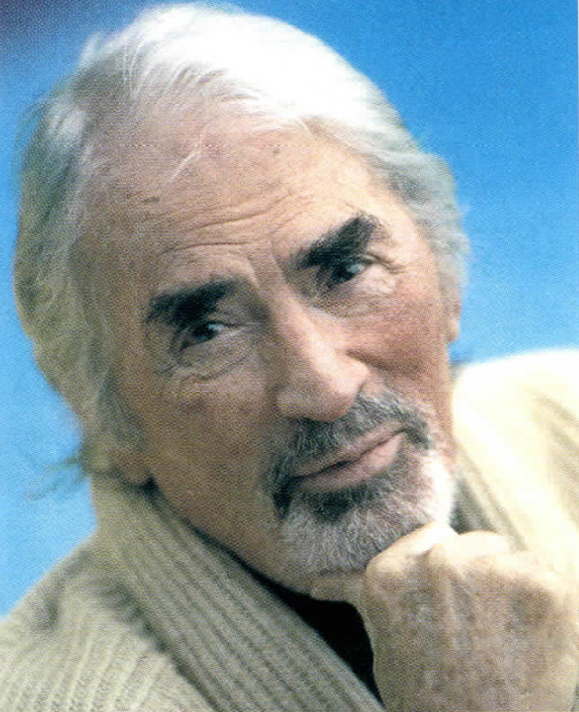

Sitting across from me in a black turtleneck, cardigan, and corduroy pants, sporting a beard, Peck at 81 looked strikingly handsome on this June afternoon in 1997. The Southern California sun shone in on the living room, a luxurious mix of overstuffed sofas, fine antiques, paintings (including a small Renoir) and photographs: of Peck’s mother Bunny on her 75th birthday, from whom he inherited his good looks; of his father (who bestowed on him his eyebrows); of two couples, the men in top hats – Peck, his pal David Niven and their wives at the Ascot races. And in the middle was a large photograph of a group with unmistakably Irish faces – 30 cousins gathered for one of Peck’s visits to Kerry.

In the foyer there were more paintings, including two racing watercolors by Raoul Dufy. Peck, an avid horseman, at one time had several thoroughbreds, including Owen’s Sledge, ridden by Pat Taafe in the British Grand National.

The study, lined with books (Shaw, Shakespeare, Yeats, Wilde, all the classics) held a portrait of Thomas Ashe, the Irish patriot, with whom Peck shared great-great-grandparents, and a lithograph of President Lincoln by Yaacov Agam. Peck had great respect for President Lincoln, and the men of the Civil War era, “for not shirking the right thing to do.” Another man he grew to respect, through his research in preparation for the movie role, was General Douglas MacArthur.

It was during the filming of MacArthur that he had bought the house, a splendid bungalow, 20 years before. He laughed as he told me how he had left the set of the movie in full uniform and still in character, viewed the property and commanded his wife Véronique to “Buy it.” And the inside? “We’ll fix it up.”

He and Véronique celebrated their 25th wedding anniversary by putting up a tent on the lawn and inviting all their friends – “Albert Finney came and brought his mother.”

Peck met Véronique in Paris after completing Roman Holiday. The then 20-year-old French journalist interviewed the American star, and Peck, smitten, called to invite her to the races. This particular day, she and their daughter Cecilia had taken the dogs to the vet. The two dogs were largely the reason why the Pecks didn’t have a summer home in Ireland, where six months’ quarantine for visiting animals is required.

Peck’s visits to Ireland became more frequent in the 1990s because of the film scholarships he set up with University College Dublin. Extremely modest when it came to his good works, he hastened to tell me that the scholarships are only a small part of the film studies program headed by Paddy Marsh and Richard Kearney, but when a project appealed to him, he was noted for his generosity.

He served as President of the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences (where he worked to protect the integrity of the Academy Awards; “the studios may cash in on our awards, but that is not why we are here”), and was a founding member of The American Film Institute, and The La Jolla Playhouse (as a young movie star he enticed major stars to his home town to boost attendance).

Appointed to the inaugural board of the National Council on the Arts by President Johnson (who awarded Peck the Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian decoration, in 1969), he traveled the country at his own expense to visit regional theaters. He was responsible for grants which saved many of them, including the now famous Long Wharf theater in Connecticut and the A.C.T., then in Pittsburgh, now in San Francisco.

Throughout his life, Peck was known for being politically liberal, and for not being afraid to take a stand on issues. Gentleman’s Agreement (1947) opened the eyes of audiences across the country to anti-Semitism, and To Kill a Mockingbird (1962) dealt with racial issues at a time when the country was in an uproar over civil rights. In the movie Peck portrays Atticus Finch, a Southern lawyer of quiet strength and dignity who defends a black man accused of raping a white woman. Peck received an Academy Award for his role, and it remained his favorite movie.

Harper Lee, who wrote the autobiographical story, said that her father Amasa Lee (on whom the character Atticus is based) and Peck shared the same characteristics. “The man and the part met,” Lee said in a telephone conversation, her Southern drawl still in evidence. “He [Peck] was a beautiful man – a man of very high intelligence. I think he would have been outstanding at anything he chose to do.” Horton Foote, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author who wrote the screenplay for To Kill a Mockingbird, concurred: “Peck is the essence of Atticus – born to play that part. He has such dignity as a man, and there’s an enormous sense of integrity about him.”

In a long afternoon that stretched into early evening, I found out that he also had, as Harper put it, “a very sharp and wry sense of humor, and was the most wonderful company in the world.” A born storyteller, he laughed a lot, pausing, coloring in the details as he answered all my questions in that wonderful voice of his. In another age in Ireland, perhaps he would have been a seanchai.

On the desk in Peck’s study sat a clay model of the Statue of Liberty, “to remind me that my grandmother and my dad came through Ellis Island.” With that in mind we began our conversation with talk of a trip to Ireland. – Patricia Harty

Have you found a favorite spot in Ireland?

I love Wicklow, but I suppose if we ever rented or bought a cottage it would be in County Kerry. I went to visit my second cousin, Kitty Curran, who is still in East Minard, about ten years ago. A modest house, and we sat around having a cup of tea, and she asked, “Would you be after saying hello to himself?” I didn’t know who himself might be, so I said, “Yes.” Upstairs we went, and himself was lying out on the bed dressed in woolen trousers, flannel shirt and a cardigan, wearing carpet slippers and with the cap over his eyes, fast asleep. Kitty shook him by the shoulder and said, “Da, Gregory Peck’s here to see you.”

Himself, it turned out, was a first cousin, and a childhood playmate of my father’s. He opened his eyes and said, “The hell he is.” He was confused because my father had the same name as I do. They told him I was in the films, I was in Hollywood, but he couldn’t quite grasp that. But he came to, toddled down the stairs, and they broke out a jug of poitin, and we all had a nip.

Later, Kitty walked me down the lane and said, “These are the foundations of the farm house where your grandmother lived, and your father lived as a boy.” I looked down the grassy, green slopes toward Dingle Bay. It was magical. That’s where I would go if I wanted to work on a piece of writing.

Did you feel in touch with your ancestors there?

I did. I saw my father everywhere.

He was born in the U.S., in Rochester, but his American father died quickly from diphtheria. So my grandmother took her infant son back to the family farm. They came back when he was about ten, and stayed. She had a lot of courage. She traveled as a saleslady, sold lady’s underthings, corsets and such, and made a success of it. She had bought an apartment house in San Diego, lived there and ran it as a business. She was able to help my father go through the University of Michigan, where he became a pharmaceutical chemist.

In 1909, there was no drug store in La Jolla, which is about 14 miles from San Diego, so she helped him get set up in business. My mother came along from St. Louis, Scottish and English descent, with a family name of Ayres. They married, and La Jolla is my home town.

Did your father ever talk about his time in Ireland?

He did. He always had a bit of a brogue, and he loved to tell stories. He used to talk about being a boy in Ireland and say that there was no entertainment other than telling stories or singing a song, or once in a while going by horsecart to Dingle.

My father was a jokester. When he was really getting on, 76, 77, with white hair, he loved to drive into gas stations, fill up, and hand them his credit card. I was already well known in the films by that time. The attendant would look at the old boy and say, “You’re Gregory Peck!” My dad would say, “Oh yes, but I’ve not been at all well lately.” That was typical of my dad.

How old were you when you went to St. John’s Military boarding school?

Ten. I was a bit excited by the idea of a military uniform, and I was getting into sports, so I wasn’t unhappy about it. I would go home at the end of each month, to my father’s home in San Diego, and he was living with his mother. They had a house alongside her apartment house that she ran. My father, being divorced and being a kind of bachelor, moved in with her. Unhappily, she was suffering from serious cancer. That would be 1928, the year she died. It was cancer of the stomach, and in those days, they didn’t know as much as they know today about alleviating the pain. At night I’d hear the most terrible groaning. In the morning, I would read the newspaper to her, so I remember exactly what she looked like, but as far as her character, I remember strength and an almost stoic way of dying, except for the groaning, which I can hear to this day. I visited her grave not long ago. My father is in the same place, Holy Cross in San Diego.

You’re a cousin of Thomas Ashe, the Irish patriot who died from force-feeding while on hunger strike.

He was a patriot. He wrote poetry, he was a bagpiper, he was a teacher. Once, years ago, we hired one of the carriages by the Plaza Hotel to ride around Central Park on my wife’s first visit to this country. The carriage driver said, “Mr. Peck, I’ve heard that you’ve got a bit of the Irish.” I said, “Yes, I have an Irish grandmother, and my father lived there as a boy.” He said, “Well, the portrait of one of your cousins, Thomas Ashe, is hanging in a place of honor in a bar in Queens.” I went out there and sure enough, in this obscure bar in Queens, there is, not a very good painting, but it has in bold letters, “Thomas Ashe the Patriot.”

Did you like the movie Some Mother’s Son, about the hunger strike of 1982?

I loved it. I was extremely disappointed that it didn’t get more attention at Oscar time, not so much because I thought they were longing to have their pretty little Oscars on the mantelpiece, but because it would have been more widely distributed. It would have given them the courage to do more aggressive advertising and wider distribution. It didn’t get enough attention. Those scenes in the jail were heartbreaking. Needless to say, it reminded me of Thomas Ashe.

You were at the Aintree when the Grand National was called off because of an IRA bomb threat. Did it make you feel ashamed of your Irish roots?

I didn’t in any way feel responsible. In human terms, I didn’t like it. I suppose some people were really frightened. Lots of people were inconvenienced in a big way if that’s what the IRA were interested in doing. But I don’t like that sort of thing, threatening people. Blowing up people.

All those mixed feelings in Some Mother’s Son. We all can identify with that both ways. Caught on the horns of a dilemma.

Did you always feel very Irish?

Yes. St. John’s Military School was run by the Sisters of Mercy, and every last one of them was Irish, and our chaplain, Father Crowley, was Irish, and our athletic teams were “The Shamrocks.” So I was heavily indoctrinated. My confirmation name is Patrick. My father’s influence on me was greater than my mother’s, because they divorced and she remarried, and traveled a great deal.

And of course they had us coming and going at St. John’s because we prayed when we got out of bed, we went to Mass three times a week, said grace at meals, we prayed before each class, studied the catechism upwards, downwards and sideways. There was no letting up! Then when we got out of the classroom, the military fellows grabbed on to us, and we drilled, and drilled, and drilled some more. So it was discipline, spiritual and temporal, in the extreme.

What was college life like in comparison?

Berkeley was a revelation to me. I felt totally free, I was on my own. I had great professors who opened my eyes to wider horizons, and I read like a madman. I was an English major. I started out pre-med, but I couldn’t cut it with the science and mathematics. I took French, Greek, and Russian literature in translation. I read all the classics. I was soaking up information. I was ready to absorb a whole different view of life. So it was all quite wonderful.

Also, I was an oarsman. I loved to crew. Eight men have to row as one. When the boat just flows, it means you’re in perfect rhythm. If I hadn’t acquired a sense of discipline in St. John’s, that would have ground it in for sure.

Berkeley was also your first introduction to the stage.

Yes. I ran into this fellow on campus one day who said he was looking for a tall chap to play in a few scenes adapted from Moby Dick. I played Starbuck, the first mate. We had a short Ahab, and the director was looking for a tall Starbuck. My chief qualification for the role.

After college you went to New York.

I was just out of Berkeley, and I jumped on a train across country. That’s when I changed my name. Gregory is my middle name. When I got on the train in Oakland, I was Eldred G. Peck. When I got off in New York, I was Gregory Peck. I didn’t know anybody. I’d heard about this Neighborhood Playhouse school down on the Lower East Side and I went and auditioned there and somehow got approved for a scholarship, which was lucky, because I didn’t have any money.

Those two Jewish ladies, Irene Lewison and Rita Morganthau, who sponsored the playhouse were marvelous. I was often broke, and once in a while I would go upstairs to their rather stylish, old-fashioned offices with pictures and nice furniture, and I’d borrow ten or twenty dollars.

They never said no; I tried not to do it too often. They were generous, good people who loved theater, ballet, the arts in general. I’m sure they thought they were serving their community by contributing to the theater and by training young people.

Didn’t Martha Graham teach there?

Martha Graham put my back out. I was seated on the floor with my legs out, trying to put my head between my feet. I couldn’t get more than halfway there and she came along behind me, and said, “Come on, Gregory, you can do better than that.” She took me by the shoulder and put her knee in my back. There was a loud snap. I couldn’t get out of bed the next morning. I could barely walk.

I had ruptured a disk in my lower back. The school sent me to an orthopedic specialist who put me in an old-fashioned canvas strap which I wore for two or three years and gradually the condition began to remedy itself, though off and on it’s bothered me all my life.

But Martha Graham was a big influence. Her discipline was unyielding. With her somewhat vague concept of true art, you could never fully understand what she was talking about. You knew that she wanted you to reach beyond yourself, to where you could express yourself in an artistic, creative fashion. For a number of years she was it in modern dance. Her company, when she was dancing with them, was really exceptional. To spend a couple of years under her influence was inspiring.

We had no hope of being dancers. The idea was to make us feel free, to move about, to express our thoughts and impulses in body language. Play a whole scene in pantomime, without saying anything. And somehow, just her own flame that burned inside her was an inspiration to us in ways that are a little hard to define. She was a major artist.

You are known for your incredible voice. Was it something you had to work on?

I honestly have never thought much about it. Whatever it is, it more or less came naturally. I used to joke about having been a barker at the New York World’s Fair in 1939. There was a giant thrill ride called the Meteor Speedway, and another barker and I alternated on a platform outside, dressed like racing drivers. And we were a half hour on and a half hour off mike for 12 hours, from noon to midnight. So I used to joke that did something to my vocal cords. A permanent barker. That was an interesting part of my life because I got acquainted with what you might call the bottom rung of show business, including the sideshow people.

Would you say the stage is your first love?

That’s true. I didn’t have any ambition to be a movie actor.

Is that why early on you turned down a movie contract?

And maybe just a bit of snobbery, too. I felt that I was a stage actor. I had escaped with my life in three important Broadway productions. I had gotten past what they called “Murderers Row,” the seven critics of the seven daily papers. There’s a certain snobbery that prevails amongst stage actors. If you can make it in New York, you can make it anywhere, so that’s why I was able to resist – it wasn’t even hard to resist the idea of a seven-year movie contract because I saw myself going back to the stage frequently. I just didn’t want anyone else deciding what I would do next.

Do you ever feel any terror before you go on stage?

The first time I had a Broadway show, it was called Morning Star by Emlyn Williams, and they entrusted me with the leading role, and the first act was one hour, and I was on at the beginning and still there at the end. I was thinking thoughts like: This is the guillotine if they don’t like me, I’m not destined to make a living at this. I was terrified. For a moment I even wondered if I could slip out the back stage door and get on a bus to Mexico. That quickly passed, because the other actors were being chipper about it. I thought: They may be just as scared as I am and are just not letting on. I think I learned a lesson that has often come in handy, that if you can’t be bold, act bold. So I launched myself on the stage and I survived. Got good reviews, much to my surprise. So yes, I’m familiar with stage fright.

I had a surprising conversation with Jimmy Cagney once. He told me that he was always terrified before the curtain went up. He said even on a new movie with the new crew, cast and director, he was tight at first until he got to know everybody, until he proved himself. It’s something we have to do because we’re putting ourselves on public exhibit, assuming we’re going to be entertaining, charming, likable, dramatic, funny — make it worth their while if they bought a ticket and came to see us. So it is a challenge and you have to have a certain kind of actor’s nerve, actor’s gumption.

Of the male actors you worked with, who did you enjoy?

Just for fun, I think Anthony Quinn. We made three pictures together. Always at each other’s throats. Made a picture with Robert Mitchum, the original Cape Fear. David Niven, a couple of pictures – the most wonderful male companion I’ve ever had. We used to have our villas near each other in the south of France. But going way back, the experience of working with Charles Laughton, Walter Huston, and Lionel Barrymore – these are great, great figures. Rich characters.

And who was your favorite leading lady?

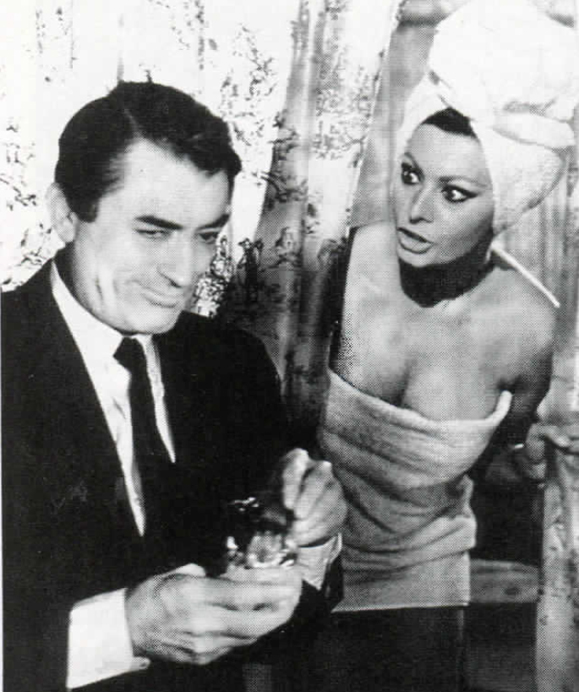

Audrey Hepburn. She was quite extraordinary. Ingrid Bergman, Sophia Loren. Lovely American girls, Jennifer Jones and Dorothy McGuire.

Did you ever work with John Ford?

No. He had Fonda, Wayne, Jimmy Stewart, he had his stock company. He didn’t need me. I made a Western called The Gunfighter which was quite good. I won the Silver Spurs award in Reno, Nevada, as the Best Movie Cowboy of the Year. I went up to get my silver spurs, and one of the first people I saw when I came back was John Wayne. He said, “Well, who the hell decided that you were the best cowboy of the year?” and I said, “Well, look, Marion, you can’t win it every year.” Six months after I won the Silver Spurs I got a script from Stanley Kramer and I thought, well it’s too much like The Gunfighter and my aim was to do a variety of things. So I said no to the script. It turned out to be High Noon. Gary Cooper won the Oscar for that. I might have done it, it might have won the Oscar, who knows? I was happy for him. No one could have done any better.

You won your own Oscar for To Kill a Mockingbird. What are your memories of working on that film?

It seems to me, looking back on it, that we were in a state of grace. In that we identified so closely with the roles. We seemed to be riding along on a stream or current in a river of emotional involvement with the characters so that the acting almost took care of itself. It wasn’t necessary to do a whole lot of research or any method agonizing. We were emotionally immersed in telling that story through those characters. I think we filmed it in only ten weeks. I could hardly wait to get to work in the morning.

You became friends with Harper Lee.

Oh yes. Even to this day. Harper came out for our first day of shooting and the scene was that I’m coming home from the courthouse or my law office, and the kids run down to the corner and the boy takes my briefcase and we walk down the street. Harper was walking by the camera, and I saw some glistening on her cheek. We did the scene and the director said, “My God, first day, first scene, first take, it’s a print.” It’s probably never happened before. So he was happy and we were happy. I strolled over to Harper, and I said, “Did I see something glistening on your cheek?” I was flattered that the scene had affected her. She said, “Oh Gregory, you’ve got a little pot belly just like my daddy.” Of course I said, “Harper, that’s great acting.”

That I reminded her of her father was the highest praise she could give me. Amassa Lee was a great hometown kind of pillar of the community. He died before the picture came out. I’m sorry that he couldn’t be around to see it himself on the screen. The story was largely autobiographical. The little boy with the buck teeth next door was actually Truman Capote, from Tupelo, Mississippi, who just happened to have an aunt living next door to Harper Lee. Some coincidence.

It did come in the midst of the civil rights movement.

It came just a year before LBJ pushed through this great program of civil rights legislation. I wouldn’t assume for one minute that the movie had anything to do with that, but it was in the mood of the times. It was issued in good climate when there was a strong national awareness that we were very much in need of this legislation that would to some extent level the playing field. It hasn’t been altogether successful, but Colin Powell has said, for example, that he wouldn’t be where he is except for the civil rights movement and, following that, the affirmative action program.

Affirmative action was voted out in California.

We take a few steps forward and then a step back. But we must never give up. I like to believe in the dream of Martin Luther King, that we can achieve it before we tear ourselves to pieces.

Tell me about being on Nixon’s enemies list.

I had produced a film called The Trial of the Catonsville Nine, which was a very powerful statement against our continued involvement in Vietnam. Nixon heard about the movie, or one of his staff did and they put me on the enemies list. It didn’t affect me one way or the other. In my eyes, the Vietnam war was of such monumental wrong-headedness – needless slaughter of human beings on both sides – the only thing that I could think of to do was that movie, hoping that a lot of people would see it and in some way it would affect the determination of our policy over there. I don’t think it did. Not enough people saw it.

I was almost literally carrying the cans of film around town to major studies, looking for distribution. I thought to take it to Robert Evans and Frank Yablans, because they had two enormous hits, The Godfather and Love Story. They agreed to see it. Bob Evans was ecstatic. He said, “This is shameful, this is a blunder of historic proportions. Everyone must see this picture,” and Yablans said, “Not with my Godfather money.”

You had a good relationship with President Johnson.

For some reason LBJ took to me. He appointed me to his National Council for the Arts. Veronique and I became almost regulars at state dinners. He was deeply sincere about civil rights and about the plight of the underprivileged. It wasn’t just politics. Although he was a master politician, and probably pulled a few fast ones. He was crafty, there was no question about that, but he was deeply concerned about the underclass. He wanted to be the President who started the country on the right road, and education was the strongest part of it. Then he got caught in Vietnam, chose not to run in ’68, was so disheartened that he didn’t get out and support Hubert Humphrey, who was a wonderful man.

He hunkered down, as they say, in West Texas on the ranch, and we would go down there after he was out of office. He was quiet. The battle was over for him. He had a bad heart. He’d always say to me, “Well, Greg, how are things in the Arts?” I’d say, we’re doing this and that. One time we were sitting around the pool, he said, “Well, Greg, how are the Arts?” And I said, “Fine. You know, this regional theater movement is doing so well, and you’re responsible for it with your Arts and Humanities Act. Wouldn’t it be great if out of that would come the American Shakespeare?” He thought about that. He said, “You know what would be even better? If the American Shakespeare turned out to be a black man.” Isn’t that great? The politician linking the arts and civil rights.

Tell me about your scholarships for Irish film students.

I have those scholarships that I give out at the University College Dublin. Film Studies. I give a modest amount and we try to raise money everywhere we can.

We must get away from this conglomerate all consuming money madness, bottom line preoccupation which exists in the film industry. Money isn’t everything. Originality, creativity, humor, new points of view about the human condition, coming from fresh sources, are all important. Otherwise we’ll be just turning out commercial properties.

Your first visit to Ireland was to work with John Huston on Moby Dick.

We filmed in Youghal only for about a week. All that John wanted there was the departure of the Pequod from New Bedford, Massachusetts, and Youghal represented New Bedford. So I didn’t get very well acquainted with Ireland on that trip. I didn’t get down to Kerry at all. We went off to Fishguard in Wales after a week.

We were there [in Ireland] because it was John’s Irish period. It was definitely the wrong place to go out to sea looking for whales. There were no whales in the Irish Sea. But John wanted it to have some kind of Irish connection. It really was a struggle.

Didn’t you almost get killed on that film?

Well, we always say that John Huston tried to kill all his leading men.

We went out day after day from Fishguard, four, five, six miles at sea with our mechanical whale. There were scenes where I had to be on the back of this creature, which was about 65-70 feet long. On a day with very rough seas, a fog bank coming toward us, very dark, ominous skies, we had no business being out there. The tow line broke on the back of the whale. The waves were slapping against the whale, probably about six or eight feet high. I was slipping and sliding trying to hold on. I wasn’t fastened to anything, as I just drifted off into this fog bank, pitching and tossing and sliding. I knew that I wouldn’t last long if I slipped off into the water, which was very cold, and I certainly didn’t know which direction to swim in, Ireland was one way, Wales another. I did actually think I could die. I imagined The Mirror in London: “Movie Actor Lost on Rubber Whale.” It went on for about 20 minutes, but it seemed like an age, before I was rescued.

We had been trying to film in Fishguard for about two months and we had about 12 minutes of usable film, and along about that point, the men in dark blue suits showed up from Warner Brothers. They came out on a launch to visit the Pequod one day and the water was fairly rough. They were deathly sick by the time they got to us, about five miles out, they were green. John greeted them at the top of the ladder leading up to the launch of the ship. One of them was Harold Mirisch and John said, “Good to see you, Harold,” and he blew cigarette smoke right in his face. They didn’t stay on board for more than ten minutes. That night there was a heavy conference, and the decision was made to move to the Canary Islands, where we should have been all the time. They had to build a new whale, the other one was never recovered. I’ve always thought it would be a wonderful children’s book – the rubber whale that went south and tried to join the whale pack and was rejected.

What was Huston like?

Huston was not known as an actor’s director. His best films were those he made with his family: his father, Walter, and later on with his daughter, Anjelica; Prizzi’s Honor and especially The Dead. He had a wonderful visual sense, and was something of a draftsman. Certainly, he was a colorful character, a fine raconteur, but I didn’t get to know him on an intimate, friendly basis.

I only knew him as a film director, and he was a director who was in big trouble. We shot 27 weeks on a 14-week schedule. The picture was greeted with mixed reviews. Now people come to me and say, I remember that picture, it was the first picture I saw. They see the whole thing in one fell swoop as some kind of mad adventure. Broad strokes. Even some people who have seen it recently seem to think better of it than the critics did when it came out. But I think of it as a lost opportunity. It has its moments, but to my notion, the picture is spotty and too short by far to tell the story.

I felt about Moby Dick that I was too young, 35, to play this malevolent, bitter old man of 65 or 70 full of hatred, longing, vengeance, with this mad obsession about the whale. I thought that in some scenes I captured it, and sometimes I didn’t always have the underpinning of emotion.

What draws you to Lincoln and the Civil War era?

I’ve often thought I’d have been better cast in the American scene a hundred years ago or more. In my mind I seem to drift back a good deal to imagining what it was like to live in America in those days. I’ve read so much about the Civil War, and so much about Lincoln, that it draws me. Why exactly? I haven’t really tried to come up with a simple answer for that, but a willingness to sacrifice – not shirking the right thing to do – not preoccupied with material things or the struggle for money and power – lack of fearfulness. Those are the things I guess that I admire the most. I find those characteristics in the people I read about so much. I’m always drawn to read about them. If I have a sleepless night I reach for one of the many books about Lincoln and read for an hour or so. It seems to do me good.

Had he run for a second term Johnson was going to make you ambassador to Ireland. Would you have taken the job?

That’s an interesting question. It was never actually put to me, but after he chose not to run in ’68, there was a grand ball for him. At a certain point he came and asked Veronique to dance, and he said, “Well, there are two of us here who love Gregory.” He was always lavish with compliments, always patting people on the back. He said, “You know, I have the thought that if I were to run for another term, I would impart Gregory as the ambassador to Ireland.” That was the whole substance of it. It was a remark he made while they were dancing at the Plaza Hotel.

Would I have taken it? Probably. I think it would have been a great adventure. It would have been interesting and new and something for me to learn and new challenges, and a whole change of our way of life.

℘℘℘

Gregory Peck is survived by his wife Véronique Passani; his sons Stephen and Carey from his first marriage to Greta Rice; a son, Anthony, and a daughter, Cecilia from his marriage to Véronique; and six grandchildren, Another son, Jonathan, a television reporter, died tragically at 30.

Had read a few articles by Patricia Harty, they seem very professionally done, would welcome any Harty comments on this article, her or Gregory Peck. There was about this actor an aura of rock convictions mix with a sometimes contrary reaction that fit all his greatest movies. As a person who cares for his fellow man my favorite of mine was the “To Kill a Mockingbird” , showing one good man’s strength against a universal evil, In this case a lone honest lawyer was defending a one armed afro american, charged with attempting to rape a white women. A black man with up until that moment had never committed any crimes! But a white woman, in a racist environment claimed it was so, and there was never any evidence! So like a Salmon swimming upstream relentlessly, with less than a fair chance fought to the bitter end for his client. Fighting though understanding from the beginning it was a futile gesture. Something the Irish have some experience with:) Thought his greatest performance:) Moby Dick I had read, but Gregory brought this superstitious sea story to a frightening, almost probable nightmare, highlighting the island Spearman with his tattoos and the mission of insanity, bone chillingly close, made you lean back in the seat when he relished that green mystical light:)