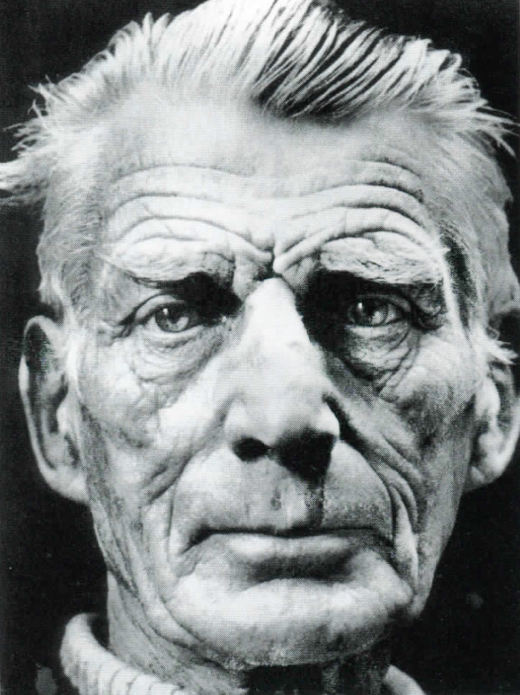

For Barney Rosset it was a special sort of homecoming. The inveterate publisher behind Grove Press had been invited as a guest speaker at Trinity College Dublin to mark the 50th anniversary of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. As Beckett’s American publisher and close friend, it was fitting that Barney Rosset should be invited. Indeed this first trip to Ireland would become a journey of immense personal significance to Rosset, revisiting the land of his grandparents.

“I’ve put off this trip for 81 years,” remarked the 81-year-old publisher, whose connection with Ireland began long before he even heard of Samuel Beckett. Both his maternal grandparents – Roger Tansey (Galway) and Margaret Flannery (Mayo) – met in the U.S. where they married and settled in Marquette, Michigan.

His grandfather, a laborer-turned-contractor, made quite an impression on the young boy. “The story was he had left Ireland under threat of death by the British,” says Rosset, not bothered whether or not the story was true. “He was loved in the neighborhood even though it wasn’t an Irish neighborhood. He was just a marvelous person.”

Barney’s mother Mary Tansey worked in a Chicago bank where she met Barney Rosset, a man of Russian-Jewish extraction. Their only child relates with glee how his mother once “won a piano in a beauty contest.” He also recalls spending time in Marquette and listening to his grandparents converse at home in Irish.

Rosset began re-excavating those genealogical roots just over a decade ago. He located the relevant documents and received his Irish passport from consular offices in New York. Ironically, by the time he got around to using it, the passport had expired. He applied for a new one and on arrival asked immigration officials to stamp it as a keepsake.

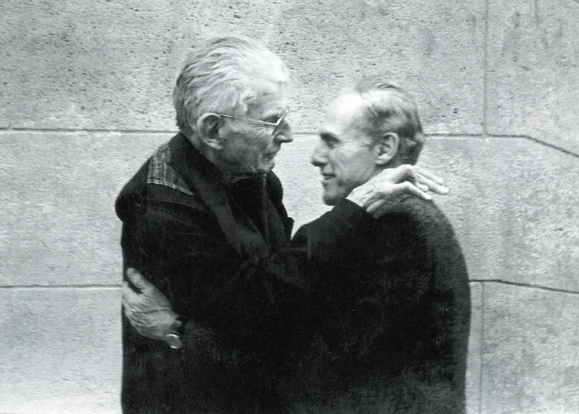

I first met Barney Rosset in 1988 in Manhattan. We became friends over the years and of all associations that come to mind the enduring image would be rum and Coke. The last time we met was in New York when he wished me a safe trip home, bestowing his blessing with a cocktail glass in his hand. And here we are five years later, on my patch this time, in Dublin. Rosset arrives into the hotel lobby holding a pint glass of rum and Coke. I suggest to him there’s a certain continuity about all of this and he laughs that familiar laugh, a swift combination of head-back dry chuckle followed by a shrug-forward intake of breath.

Technically speaking, this was his second time in Ireland. He recalls stepping briefly onto the tarmac at Shannon Airport in 1948 en route to Italy. He sees that Dublin today is growing fast, it’s both modern and ancient but just another European city. The Chicagoan may be a naturalized New Yorker but drop him in Ireland this time round and the West is already calling.

Even so, when he addresses the student gathering at Trinity, Barney Rosset feels the emotion sweep up in waves. Beckett, his old friend, was once a student within these walls. The publisher produces his newly-minted Irish passport from an inside pocket, indicating he’s here, at last. The moment passes. As soon as he finishes his speech he’s done with Dublin and is itching to retrace his ancestral path due west.

Rosset has long believed in the rights of small voices. Cherished by his parents as an only child and encouraged by teachers at the highly progressive Frances W. Parker School, he developed an outspoken confidence in his early years. School was also where he met his first wife, Joan Mitchell, a painter who later became one of Beckett’s closest friends in Paris.

Politically, the young Rosset soon found tides to swim against, fueled by an anti-establishment ethos he attributes to his grandfather. He was also attracted to Communism until he discovered that its advocacy of free love was all talk and little action. After a year at Swarthmore College, he joined the U.S. Army Signal Corps and was despatched to China as a cinematographer in 1942. “China was a dumping ground for people the Army wanted to get rid of,” he smiles, knowing that the Army was less than charmed by radical chic.

Back home he set about producing Strange Victories, an anti-racism movie. “It was a failure,” he says without remorse. “It took over two years to make and in the end I didn’t even like it.” Years later he would try again, persuading Beckett to script a movie called, typically enough, Film. Starring Buster Keaton, it failed commercially but he laughs at the memory of a $500,000 offer for the film rights of Waiting for Godot.

“I got it all screwed up,” he admits. “Steve McQueen was going to be the lead and Beckett asked me what McQueen looked like. I didn’t know who Steve McQueen was – I got him mixed up with James Garner – so I told him he was a big, husky, heavy-set fella.

“And Marlon Brando was supposed to be in it and I said he was also very big and heavy. And Beckett said, `Oh no, my characters are shadows.’ So he turned it down in one minute. Later I thought I’d made a terrible error and if I’d known, I’d have told him they were both short and skinny guys.”

Failure with Strange Victories turned his attention to publishing and in 1952 he got wind of a fledgling company up for sale. With $3,000 he bought Grove Press, an unknown publishing house “with three suitcases of books” in Greenwich Village. Little did he know that Grove would prompt an upheaval in American publishing with reverberations all around the English-speaking world. “I didn’t know what was good or bad,” he admits. “I knew nothing about publishing.” Typically, Rosset’s justification for getting involved was that “it was interesting.”

For such a strong-willed and highly motivated individual, publishing in 1950’s America became a symbiotic match of personality and opportunity. Although he began by reprinting Henry James’ The Golden Bowl, the real story began when Rosset decided what books he wanted to publish. Somewhat inevitably he took the hard road, choosing D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterly’s Lover, which had been banned in the U.S.

Grove deliberately pitted itself against the U.S. Post Office because the postal authorities deemed the book “obscene” and “unmailable.” The strategy went according to plan “almost like we’d written out the scenario perfectly.”

The ban was duly lifted and the book, uncut, went on general distribution. Even at that stage, however, Rosset had a pre-set plan to publish Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer. “On Lady Chatterly’s we contained the battle to relatively few opponents but with Tropic of Cancer it went berserk. We were arrested all over the U.S. hundreds of times!

“It was a fantastic time,” recalls Rosset, who opposes censorship of any kind. “For me, the high point was taking it to the State of Illinois court in Chicago, which was the only time during the whole thing I personally appeared in court. It was like coming home and we won.”

By that stage he and Samuel Beckett were already familiar to one another. Their relationship began when Rosset read a couple of submissions the Paris-based Dubliner had contributed to Transition magazine. “I was intrigued,” says Rosset when he heard that Beckett’s play En Attendant Godot had opened at the Babylon Theatre in Paris.

Having paid a $150 advance on the American rights, he boarded a liner in New York and sailed for France on honeymoon with his second wife, Loly Eckert. They met Beckett at the bar of the Pont Royal Hotel and a long night ended with the author buying champagne for the newlyweds. Their marriage did not last, but the trio’s rendezvous was the beginning of an enduring friendship between Rosset and Beckett.

The publisher wrote from New York on June 13, 1953, advising, “We will do what we can to make your work known in this country. The first order of business would appear to be the translation. If you will accept my first choice as translator the whole thing will be easily settled. That choice, of course, is you.”

Beckett replied on June 25. “I will send you today or tomorrow my first version,” he wrote.

In its first year Godot sold 341 copies. “It wasn’t a big smash hit,” smiles the publisher. “We didn’t expect anything different. The money part was quite irrelevant because it cost us more to get to see him in Paris. We went to tremendous trouble to make it a handsome book in hardback and there was no way we expected to sell it in a big way. But it was a good play – a great play – so I thought, don’t worry about it!

“When I signed for the rights I remember showing it to a professor of mine – Wallace Fowlie at the New School in New York – who was someone whose view I really respected. He read it and said, `I think it’s a great play and without doubt Beckett will be considered one of the greatest authors of the twentieth century.’ That meant a lot to me.

“When we released it in paperback it was our 33rd book – I had waited for my favorite number to come up – and it began to sell. We worked to make it famous on university campuses in America, and it must be one of the best-selling plays in the history of American publishing.” By now Godot is regarded as a timeless classic and has sold close to two million copies worldwide.

Maybe it’s how everything comes around. On the very evening Barney Rosset was invited to speak in Trinity, the Gate Theatre in Dublin revived a production of Godot to commemorate the play’s 50th anniversary. Just as Barney made his way to the lecture hall to talk about Beckett, a ticketless queue formed at the Gate box-office in the hope of late cancellations – everybody waiting on Beckett, 14 years after his death. It is quite an achievement for a writer who extolled the utter inconsequence of existence.

Grove Press cultivated beat writers like Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs and Jack Kerouac. Rosset had other notable successes with Grove, including The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1964), William S. Burroughs’ Naked Lunch (1968) and Last Exit to Brooklyn (Hubert Selby Jr., 1969) as well as publishing works by Brecht, Behan, Ionescu, Genet, de Beauvoir, Sartre, Duras, Havel, Rechy, Pinter and others.

“It was highly unusual,” he realizes. “We never paid large advances and literary agents never came to us. We really didn’t do anything we didn’t feel like doing. I was able to sell a lot of books and also get people to invest in the company. At the beginning I didn’t know writers but it gradually sunk in with me that writers are much more isolated than painters. In my experience writers needed help, even if they didn’t know it.” Many writers felt that Rosset and Grove became more champion than publisher. “Yes, absolutely!” he replies enthusiastically. “And we were.”

However, the publishing world changed and Grove found it increasingly difficult to compete with the new giants. It led to an acrimonious takeover in 1985 and after 35 years on Houston Street, Rosset was out. Characteristically, he set up Blue Moon Books and started again. Beckett, after whom Rosset named one of his four children, refused to write for Grove and handed Stirrings Still to Blue Moon, dedicating it to the lone publisher. It was Beckett’s last work.

In 1988 the Writers’ Association PEN awarded Rosset its publishing citation. “It is more than writers who are in his debt,” noted the award. “Publishers who serve literature are not uncommon; publishers who serve culture are. Barney Rosset is such a publisher.” For reasons still unclear, PEN overlooked Rosset in last year’s tribute to Beckett, a slight that irritated if not upset the indefatigable publisher.

Blue Moon has since gone into bankruptcy after getting mired in a virus-like lawsuit that originated with third parties in Las Vegas. Bouncing back once more, he set up Foxrock Publishing, named after the birthplace of his “first and foremost” author.

Rosset’s visit to Ireland this year would have meant little had he not gone west. On a bright windy Saturday we set off along the N6, rolling out on one of the new motorways that feed the growing capital. The suburbs extend for miles stretching outwards to envelop the small towns of County Dublin, Kildare and Westmeath as city satellites.

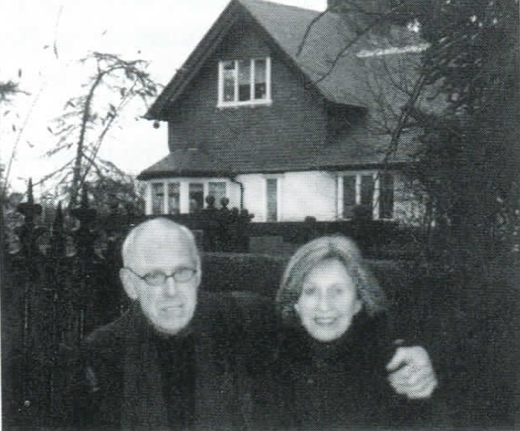

Traveling the road with Astrid Myers, his partner of 15 years, the fearless defender of small voices takes it all in. He’s surprised by the quality of the road and how built-up Dublin actually is. And then we clear some undefined boundary to behold green fields and grazing cattle. A rural setting. Picture postcards.

The man with the single-stamp Irish passport grew quieter as we closed the distance to his grandfather’s birthplace. Crossing the River Shannon at Athlone seemed like a gentle delivery into folk memory, images framed by stone walls and wind-bent trees. Barney watched it all in silence. “You got the camera, Astrid?” he checked nervously, as though concerned these pictures might slip away.

Arriving in the village of Ballyforan in County Roscommon, he was surprised to see a bar named `The Big Apple.’ Either the world is definitely getting smaller or this was a homecoming with a difference.

We pulled in, awaiting Barney’s relatives. They would receive us with warm hospitality and later bring us to Roger Tansey’s original holding on the Galway side of the River Suck. For now, we’d just have to wait a few minutes. Astrid took a photo. Barney stood in silence. A young boy turned the corner to find three strangers waiting aimlessly on the side of the road. “Are ye lost?” he asked, echoing a line from a now famous play. ♦

Leave a Reply