From acclaimed actors, musicians, novelists and sports writers, to daring athletes and caring doctors, we lost some of our finest citizens in the past year, including William McCool, one of the seven astronauts who died in the space shuttle Columbia tragedy and two gifted, world famous entertainers, singer Rosemary Clooney and actor Richard Harris.

℘℘℘

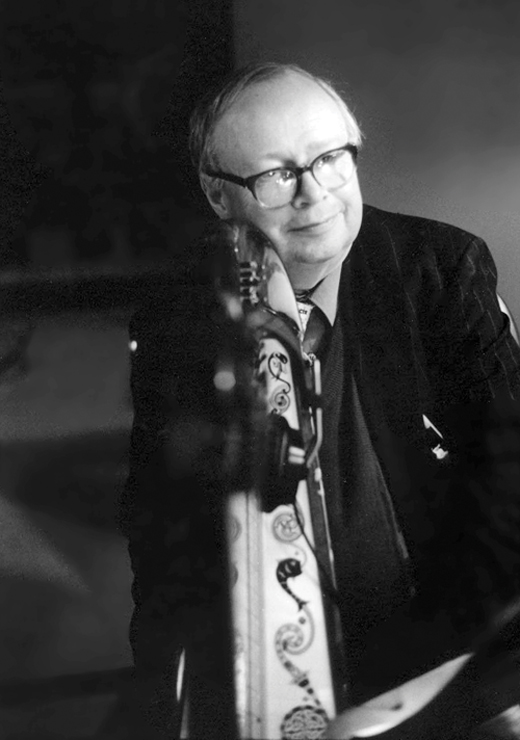

Most notices of Richard Harris‘ death in October emphasized his appearance in the 2001 blockbuster movie Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. Harris played Albus Dumbledore, the wise headmaster at Harry Potter’s school for wizards. (Harris starred again in the sequel Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets.) This focus was a bit troubling given Harris long, illustrious career. Harris’ high point — admittedly, his tumultuous private life was equally dramatic — had to be his 1991 role as Bull McCabe in The Field. Harris was nominated for a best actor Oscar, and though he didn’t win, it’s not likely you’ll ever see as fierce a performance onscreen. Harris, as a farmer who does not want to sell his land to an American, literally seems to tear up the screen in the Jim Sheridan-directed movie. He had earlier made his name on stage, and with small roles in 1961’s The Guns of Navarone and 1962’s Mutiny on the Bounty, with Marlon Brando. Harris gained further popularity in the 1967 musical Camelot, starting as King Arthur in the movie about the Knights of the Round Table. Harris later had a leading role alongside Sean Connery in The Molly Maguires, about the infamous Irish mineworkers union in Pennsylvania. By this time, Harris had also earned his reputation as a bad boy. According to legend, movie directors would add a week to their shooting schedules, to accommodate Harris’ hangovers.

He was born in Limerick in 1932. A youthful passion for sports was curtailed when he contracted tuberculosis. He learned he had lymphatic cancer last year. Reportedly, when doctors told him, Harris said it was remarkable he had lived long enough to develop the disease in the first place.

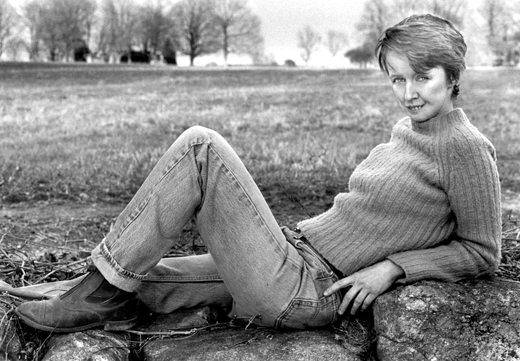

Singing legend Rosemary Clooney died this past June after a long battle with lung cancer, in her hometown of Maysville, Kentucky. She was 74. Her grandmother came from Kilkenny, and Clooney grew up in Depression-era Kentucky. Yet she became a wildly popular star by the time she was just 23, when “Come-on-a My House” topped the charts in 1951. She would stay in the entertainment business for five decades.

“Rosemary’s one of the most natural, effortless singers I’ve ever heard. She has a gift that few vocalists are ever blessed with, the same warmth and spirit she had 50 years ago when we first started out together,” legendary crooner Tony Bennet once said.

Shortly before her death, Clooney told Irish America: “The older I get, the more Irish I feel.”

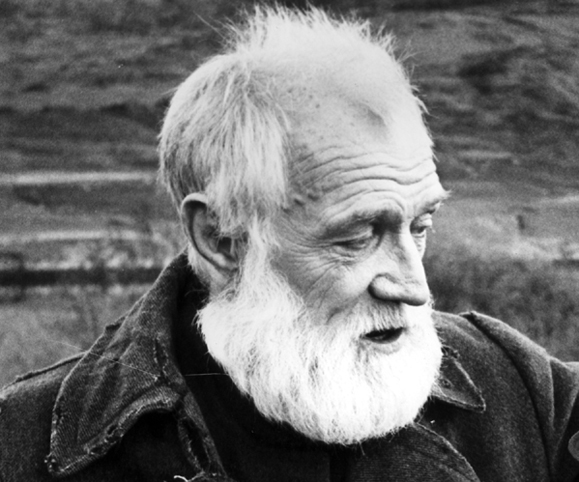

The musical world also lost beloved member of The Chieftains Derek Bell, who died at the age of 66. Born in Belfast in 1935, Bell was a child prodigy who wrote his first concerto at age 12. Bell went on to become an integral part of the world famous Chieftains, which he joined in 1972. Widely considered to be one of the finest harpists in the world, he also had a successful solo career.

Particularly sad, given her young age and difficult life, was the death of Lucy Grealy, who died in New York City this past December at the age of 39.

Grealy’s frank, brutally honest 1994 memoir Autobiography of a Face — about what it is like to be deformed in a world obsessed with beauty — was a hit with critics and readers alike. More recently, however, friends said Grealy suffered from severe depression. The specific cause of Grealy’s death was never announced, though she had undergone a series of surgeries for a rare form of cancer.

Born Lucinda Margaret Grealy in Dublin, Lucy was one of five children whose father Desmond was a founder of the Irish national broadcasting network RTÉ. When Lucy was 4, the family moved to Spring Valley, New York. Grealy was later diagnosed with Ewing’s sarcoma, a rare cancer that began as a dental cyst. At 9, Grealy started to undergo chemotherapy and radiation, often five times a week for five years. The treatments dissolved nearly half her jaw-bone. Grealy survived the cancer, but it took 30 operations over 18 years to rebuild her face.

Two more great writers — in very different fields — also died: historical novelist Thomas Flanagan and Boston Globe sports columnist Will McDonough.

Flanagan was a pioneer in Irish literary studies and historical fiction, whose epic 1979 best-seller The Year of the French won the National Book Critics Circle Award. It was in the strife and tragedy, the saints and scoundrels of Irish rebellion that Flanagan found his muse. But his path to literary fame was, to say the least, indirect.

After years as an academic, who dabbled in detective stories on the side, Flanagan burst onto the literary scene in 1979 with The Year of the French. The sweeping saga chronicled the mythic events in Ireland in 1798, when Irish and French forces banded together against the British. Flanagan followed with The Tenants of Time (1988), another historical saga, this time set around the Fenian uprising of 1867. The End of the Hunt, published in 1994, was Flanagan’s final novel, and explored events from the Easter Rising through the 1920s Irish Civil War.

Born in 1923, into an upper middle-class home headed by an Irish Catholic doctor, Flanagan spent his youth in Hastings-on-the-Hudson in upstate New York, friends said. (The writer Truman Capote was a high school pal.) Flanagan’s grandfather, a committed Fenian who owned a brick factory in upstate New York, was one of several family members who eventually appeared in his novels.

Flanagan is survived by two daughters. His beloved wife, Jean, died a year earlier.

Will McDonough, meanwhile, covered sports in Boston for well over four decades, and was also one the most recognizable voices of football on Sundays on TV from 1986 to 1998. McDonough brought his Boston Irish origins with him wherever he went — even network TV. His Southie accent was as thick as it was unmistakable.

But it was as a newspaper man that McDonough made a name for himself, joining the Boston Globe just after he graduated Northeastern University in 1959. His columns were widely read and hotly debated, and up until the time of his death McDonough had covered every Super Bowl ever played.

McDonough died in January 2003 at the age of 67, following a mild heart attack. He is survived by his wife Denise, two daughters and three sons, including Sean, who followed in his Dad’s footsteps and is now a broadcaster for ABC Sports and the Boston Red Sox.

A different corner of the sports world also suffered a tragic blow when snowboarder Craig Kelly was among 21 people killed when a wall of snow fell on them as they were skiing the Durrand Glacier. Though only 36, Kelly was considered a groundbreaking athlete, who won numerous snowboarding championships. Many say he was instrumental in bringing the sport to the Winter Olympics in 1998, though by then it was too late for Kelly to compete in what is very much a young athlete’s game. Kelly, who grew up in Mount Vernon, Washington, first discovered snowboarding in 1981, Craig’s dad Pat told the New York Times. “He had won several national titles on BMX bikes. His bike sponsor took him to a mountain to try an early snowboard that you steered with ropes, and he was hooked.”

Craig Kelly is survived by companion Savina Findlay, their daughter Olivia, his mother, two brothers and two sisters.

The Irish American sports world also lost Joe McCluskey, a 1932 Olympic medalist who won more U.S. Track and Field titles than any other runner. McCluskey, a standout at Fordham and later a World War II veteran after winning a bronze at the 1932 Olympics, died at the age of 91 in his native Connecticut.

Dr. Michael McFadden apparently never forgot how important a little help can be when you are down on your luck. Born in Donegal, McFadden’s family emigrated to Scotland in an effort to escape grinding poverty. McFadden’s father died in Scotland, however, leaving his mother to raise six children.

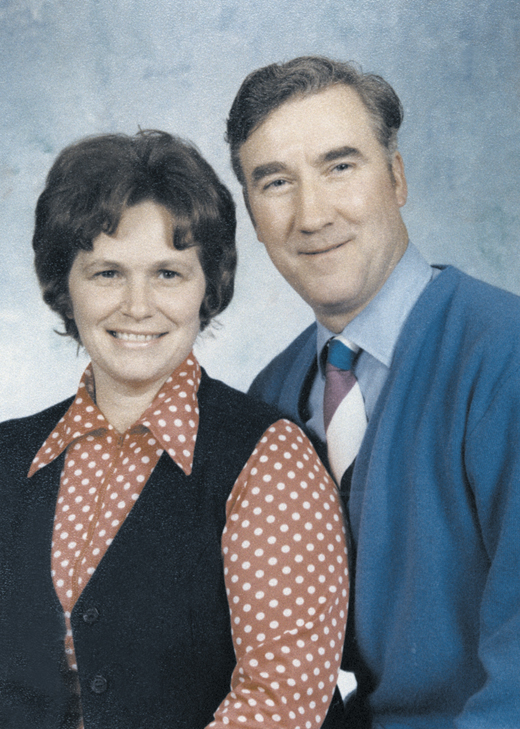

When McFadden ultimately became a successful San Francisco doctor he would treat patients and accept whatever fee — if any — they could pay. McFadden died in December at the age of 77, in the home where he and his wife Mary raised ten children.

Despite his family’s tough situation, McFadden received good grades in school and eventually earned a degree in Medicine from Glasgow University. In 1956 he met a San Francisco girl named Mary McKenna, while she was vacationing in Ireland. When the couple eventually settled in San Francisco’s Noe Valley district on 24th Street, locals praised him for his generosity, never taking more money than a patient could afford to give, and also making regular house calls. McFadden was affectionately known as the “mayor of Noe Valley.”

The matriarch of one of the most famous Irish American political families died in February. Eleanor Daley, 95, was married to Chicago mayor and so-called “president maker” Richard Daley, who ruled Chicago for well over two decades. Their son Richard M. Daley is currently mayor of Chicago, and another son William served as Commerce Secretary in the Clinton Administration. Eleanor and Richard had two more sons and three daughters, one of whom died in 1998.

Eleanor, who was known as “Sis,” lived her whole life in the tight-knit Irish community of Bridgeport. She avoided the spotlight, but was a key adviser to both her husband and son, helping a Daley run Chicago from 1955 – 1976 (her husband) and then again from 1989 to the present.

One of the seven astronauts who died in the Columbia space shuttle tragedy, William McCool, had deep roots in Ireland. His relatives in Donegal — from where his grandfather Joseph emigrated to Boston 70 years ago — mourned the passing of the 41-year-old hero. One cousin, 82-year-old Anna Kemmy, said the family kept in touch over the years with the McCool family in Texas, who even returned to Ireland several times for family funerals. As with the rest of the nation, Kemmy described McCool’s death as a great tragedy.

The dedicated Irish American peace activist Phil Berrigan died at the age of 79 on December 6, 2002. He spent his life advancing the cause of the poor and campaigning for peace and nonviolence. A veteran of WWII, Berrigan began his work as an activist in 1966 protesting the war in Vietnam, and up until his death he condemned the war in Iraq and the proliferation of nuclear weapons.

He died at Jonah House, a community he co-founded with his wife Elizabeth in 1973 in Baltimore, Maryland. The Jonah House members live and pray together and attempt to expose the violence of militarism and consumerism. Berrigan’s illness was brief; he was diagnosed with cancer of the liver and kidney two months before he died.

Berrigan was frequently incarcerated for his activism, and was in prison just one year prior to his death. Altogether, he spent almost 11 years in jail. He was dedicated to his causes, including one that involved communicating with others. He insisted on personally responding to every phone call and letter he ever received, and once said, “Gandhi had answered everyone who ever wrote to him, and he had more letters than I ever have.” He also published six books including an autobiography, The Times’ Discipline.

A deeply religious man, Berrigan was ordained a priest and once said that he got authority for his activism from the Bible. His brother Daniel, a Jesuit priest, officiated his last rites on November 30. He is survived by his wife Elizabeth McAlister and his children Frida, Jerry and Kate. ♦

Leave a Reply