The history of the Moran tugboat family, once known as the “Irish Navy” in the Port of New York, is explored by Marian Betancourt.

To say the Irish had a lot to do with making New York a great maritime port is no blarney! Not only did they do most of the towing, they dug the Erie Canal, which made New York harbor the gateway to the West. In fact, it was because relatives here said “the Irish have most of the jobs in the ditch” that Thomas Moran, a 61-year-old unemployed stone mason from Kill Lara, County Westmeath, brought his family to America in 1850.

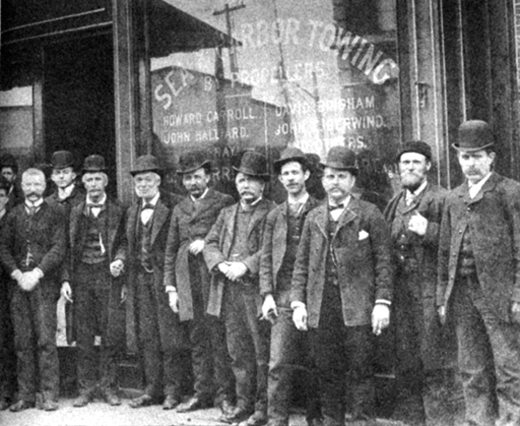

It was Thomas’ second oldest son, blue-eyed, black-haired Michael, who had the vision and the big dreams while driving mules along the canal towpath. By the time he was 22, he was operating his own towboat. Then, at 27, with his savings in his pocket, Michael said goodbye to his family and told his sweetheart he would be back to get her. He traveled down the Hudson on a grain barge with the dream of opening a towing brokerage office in a port teeming with shipping. For $10 a month, Michael rented a desk in a bar at 14 South Street and Moran Towing was born in New York Harbor. Today it is the largest marine transportation company in the East and Gulf states.

The Commodore

Before Michael Moran brought order to the chaos of towing, many tugs would race to the mouth of the harbor for an approaching ship and wage a bidding war through megaphones. Sometimes it got physical, with tugboaters tossing shovels, frying pans, and anything else they could find to quiet their competitors. Michael decided tug-boaters might do better by banding together instead of battling on alone and soon he was handling towing for nearly 20 ship captains. He worked long hours and drove a hard bargain but gained a reputation for honesty. He soon bought two secondhand tugs of his own.

After years of working with mules, Michael had developed a certain style of toughness to get through men’s stubborn habits. If he found his crew drunk and brawling, he would grab them and bang their heads together, while quoting scriptures and admonishing them. Michael was also impatient with profanity and ordered his crews to find substitutes for strong language. Experiments with “shucks” and “drat” didn’t last. While Michael would brook no nonsense, he was described as gracious and compassionate. “No effort was ever spared to help anyone in need,” his grandson Edmond J. Moran said years later.

Business was good but Michael’s life was not yet complete, so in 1862 he went upstate and married Margaret Haggerty in St. Mary’s Church in Albany. He brought her back to an apartment in Red Hook, Brooklyn, near the Atlantic Docks where his tugs were kept. As his family expanded, Moran bought a house at 107 William Street (now Pioneer Street). Michael and Maggie had a daughter and five sons, each virtually weaned in the pilot house. Eugene, born in 1872, was the third child and would eventually run the family business. His brothers were Richard, William, Joseph, and Thomas, whose son Edmond would later succeed Eugene. Agnes married J. Frank Belford, who also worked in the company.

Michael was of medium height but his large frame made him appear bigger. He wore a black coat, kept open, and a heavy watch chain with a small compass bounced over his belly. “In his blue eyes a twinkle was usually lurking,” recalled his son Eugene. “He laughed a good deal.” His charm and savvy kept Michael on the good side of Tammany Hall at a time when New York was the largest Irish city in the world. He got the exclusive contract for moving the city’s garbage out to sea. A few years later, Moran tugs would tow away the excavated rock from the city’s first subway tunnels. At the 1889 centennial of the British evacuation of New York, Michael was designated the honorary commodore for tugs in a big marine parade. The title stuck, and fellow boatmen began calling him the “Commodore of the Irish Navy.”

Although a staunch Democrat, in 1896 Michael was so adamant about the danger of William Jennings Bryan’s fiscal ideas that he put posters and banners all over his tugs urging votes for McKinley for president.

Michael was good to his family and a question he proudly asked of the South Street cronies he brought home for dinner was: “How do you like my crew?” His first brand-new tug, the Maggie Moran, was named for his wife. “It was a great day for Father and Mother, as it was for us kids, when the tug was commissioned in 1881,” Eugene later wrote. “We climbed and poked over every nook of the vessel.” Sadly, Maggie Moran died two years later at age 42. Three of their sons would also precede Michael in death. Richard died of consumption at 26. Thomas died at 39 and William at 27.

The Dean of the Harbor

Michael’s son Eugene may have been the most colorful of the Morans. This dapper little man — the press always described what he wore — became a huge influence on the events of the harbor. The governor appointed him a commissioner of the new Port Authority of New York and he played a leadership role in all the port’s maritime organizations. He quickly established himself as a marine oracle and gave the impression that he owned the harbor and was only letting others use it. Nevertheless, his opinions were carefully considered because he was usually right. He encouraged development, raised a ruckus when anything threatened it, like putting La Guardia Airport on Governor’s Island, or Robert Moses’ idea to connect Brooklyn, and Manhattan with a bridge rather than a tunnel. And he protected the harbor, too, understanding even then the importance of wetlands to the health of the port.

In his youth, Eugene did not foresee this future. His heroes were seamen and he wanted to work on the tugs like his brothers. With little interest in school, and after much pleading, his father gave him the chance to start at the bottom with no special favors. At 14 he went to work with Peter Cahill, his father’s friend and business partner, who loved to sing “Rock of Ages” at the top of his lungs while piloting the tugs. As it happened, the day Eugene reported for work, the cook failed to show up, so he was drafted into the galley. He also worked as a deckhand, but Michael recognized that his son was too small for the muscular work and had a better aptitude for the administrative end of the business.

Eugene had endless curiosity and the energy to go with it. He learned all the different jobs in the company and knew everyone who worked there. He was no less involved in social and church activities and at 25 married the equally vivacious and popular Julia Claire Browne. They had two sons and four daughters.

The Moran company began the 20th century with tugs working all along the Atlantic coast. In 1905 the company was incorporated with Michael, 73, as president and Eugene, now 34, as vice president. Michael’s son Joseph, several nephews and a son-in-law also worked in the company. In 1906, the year of Michael’s death, the company moved to 17 Battery Place at the tip of Manhattan. The building had a narrow ledge on the 25th floor where orders could be shouted through a six-foot megaphone to the tugboats in the harbor below. Nothing thrilled Eugene more than to be up there watching Moran tugs pushing and pulling all over the harbor. At the end of World War II when the Queen Mary, carrying troops back from Europe, was spotted approaching the harbor, Eugene grabbed a pair of binoculars, according to The New Yorker, “and with his white hair flying, ran like a deer up six flights of stairs to the roof.”

In 1917, Franklin Roosevelt, then Secretary of the Navy, commissioned Eugene a lieutenant in the Naval reserve because he knew more about New York harbor than the Navy did. He was part of a three-man committee to quickly assemble a fleet of small craft for the British, who badly needed patrol vessels. Eugene also chaired the Joint Committee on Port Protection, which kept a sharp eye out for sabotage. He even helped capture a German spy living at Sandy Hook, New Jersey, by watching a suspected house. When he saw a plume of sparks shooting up from the chimney, he notified the officials, who found a hidden telegraph. Eugene was promoted to Lieutenant Commander.

The media loved Eugene Moran, not because of his maritime expertise or vocal opinions. They loved his style. Here’s what Robert Lewis Taylor wrote for a 1945 two-part profile in The New Yorker, “The Elegant Tugman”:

“The president, who is five feet five inches tall, has white hair parted on one side, and a permanent look of impish gaiety. As a result of riding tugs in all kinds of weather, and of using a sun lamp, his face and hands are fashionably tan. He has a great variety of upper-class clothing, much of it quite rakish, and dresses with country-club precision even if he’s only going across the harbor with a barge full of fertilizer.” The writer continued, “Stokers have been known to crawl up for a look at him, after rumors of a particularly catchy ensemble, and then, much stimulated, crawl back and stoke like crazy men.”

On his 80th birthday, The New York Times ran the headline: “Moran ‘Too Busy’ to Mark Birthday. Now 80, Tug Chairman and Dean of Harbor Still Has Many Irons in the Fire.” Even in his retirement, Eugene went to Port Authority meetings twice a week. Occasionally he would host officials from other countries who wanted a harbor tour on a tug. He also wrote a book with Lewis Reid: Tugboat: The Moran Story, published by Charles Scribners in 1956.

After his wife died, Eugene bought a house in Bay Shore where his family had summered for years. He liked to fish from his 36-foot cruiser, Off Shore, on Great South Bay. For relaxation, he read history, biography, and mysteries, stimulating an inquiring mind that didn’t call it quits until the age of 89.

The Admiral

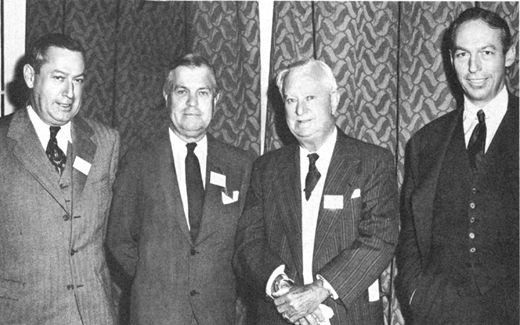

Company leadership passed to Eugene’s nephew and Michael’s grandson, Edmond J. Moran, who had been working on the tugs since his school vacation days. Edmond never wanted to do anything else. He was proud of his pilot’s license and often took the wheel when aboard one of his tugs. “We in the tug business think of our tugs as the propelling power behind the complex machine that is New York,” he said in a 1965 address to the Newcomen Society. Edmond lived to be 96 and worked in the company for 69 years.

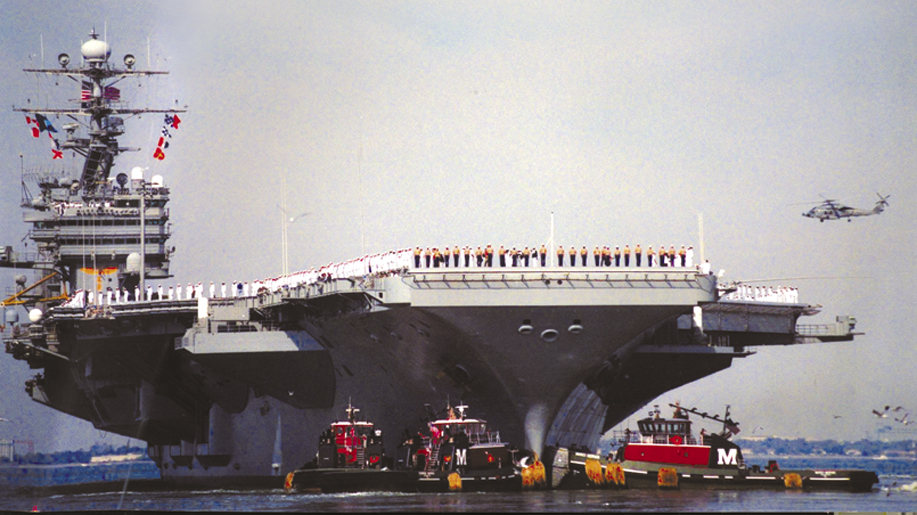

As a World War I Navy reservist, Edmond returned to action when World War II began. Considered one of the greatest experts in tugboat operations in the world, Edmond was selected by the American and British navies to plan how and when to deliver two artificial harbors to Normandy to support the invasion troops. This idea was scoffed at until Edmond said it could be done and proceeded to do it. He organized the largest fleet of tugs ever assembled, and the massive structures, described as the eighth wonder of the world, were towed across the English Channel.

For this heroic deed, the newly named Rear Admiral Moran received (among others) the U.S. Legion of Merit, the French Croix de Guerre, and the Order of the British Empire. Perhaps the most rewarding honor came in 1944 when an American Liberty Ship was named for Michael Moran. The whole family went to the Maine shipyard for the launch followed by a lobster picnic. The ship was christened by Nancy, one of six children of Edmond and his wife Alice Laux who were married for 63 years.

After the war, Moran Towing had its greatest development as Edmond guided the expansion from Maine to Texas and inland on the Great Lakes and the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers. In 1947 they made history with the longest single tow of 12,996 miles from Tampa to the East Indies with two huge mining dredges.

In 1964, the Admiral’s oldest son, Thomas, took over the presidency for the next 30 years, but the company was losing its family domination. The passion of the early Morans was gone, and to expand, the company began to look outside the family. Eugene’s two sons had retired, and his grandson Eugene III left in 1980.

In 1973, the company moved from Battery Place into the 50th floor of the yet-to-be-completed World Trade Center. In the early 1980s, they moved to Greenwich, Connecticut. With operations all over the country, there was no longer a need to be in New York City. During Thomas Moran’s tenure, and shortly before he died, the company was sold to the Tregurtha family.

The Last Moran

Ned Moran, 57, is the youngest son of the Admiral, 20 years younger than his brother Thomas. After graduating from Georgetown University and serving in the Navy in Vietnam, Ned began working in Moran sales in 1971. He moved to finance and accounting, then managed company operations in Jacksonville, Houston and Baltimore, before coming to headquarters. When the new owners took over, Ned was asked to stay on as Senior Vice President in charge of the harbor companies.

Ned is most proud of the Moran’s contributions to the government during times of crisis. During the Spanish-American War, the first American vessel in Havana harbor was the M. Moran, a tug chartered by James Gordon Bennett for his New York Herald reporters. In addition to the service in both World Wars, Moran also towed cargo to DaNang for the Navy in the Vietnam War.

While Ned may be the last Moran in the company, he has not lost his interest in the family lore. As a boy he sailed on his father’s sloop Killara, a name taken from the town where the Morans hailed from. But when Ned visited Westmeath years later, he could find no such town as Kill Lara, and no record that stonemasons had ever worked in Westmeath.

Whether or not that mystery is ever solved, there are now six generations of Morans — hundreds of them around the world — from the family of Michael Moran. They are teachers, bond traders, journalists, photographers, and real estate lawyers. In Ned’s own family, his daughter Amy is a clinical social worker at Johns Hopkins Medical Center. His son Ned (Edmond J. III) is a software engineer in Washington, and daughter Meg is a business consultant in New York. Ned’s wife Judy is a psychologist, nurse, and family lawyer. Not a tugboater in sight, but tugs with the big white M are still pushing and pulling in New York and a dozen other harbors. ♦

The Westmeat Morans hail from Cavan and are closely related to the Leitrim Morans!!! Killara is located in Cavan!!! I hope I can help the Moran family

Thank you, from Michaels great great grandson. Michael

Dear Irish America Staff, I am seeking information on Charles Moran Jr. He raced an MGTC sportscar at Watkins Glen,NY in the first post World War 2 auto race in America in 1948. Was he connected to the Moran Tugboat family? The owner of a MGTC has asked the International Motor Racing Research Center to find details on a car he bought at auction recently. The man who placed it for auction said that he couldn’t remember who he purchased it from in the late 1950’s ,but that the family were in the Tugboat business. So, googling around I found Moran Towiing, but their website history dosen’t mention a Charles Moran or Charles Jr. So, any help you can provide would be appreciated.. Thanks in advance. Rick

Greetings All,

Eldest daughter of immigrant Michael J Moran whom arrived with his sister in NY Harbour on the 4th of July. I, Mary Ann Moran am after a print of your fine tug bearing mine & me grandma’s name, in any event I loved reading the above & I thank you for any guidance on possible purchase.

Warmly,

Mary Ann Moran

moranshine7@gmail.com