From King Kelly to Mark McGuire, Ron Kaplan traces the Irish influence in baseball.

Irish ballplayers have helped to shape baseball ever since the game took its first foundering steps on the playing fields of New York and New Jersey over 150 years ago. Their impact is still felt. While no official organ of the game keeps records of ethnicity, one only has to glance through one of the massive reference works, such as Total Baseball, to peruse the scores of Irish surnames that fill the players’ register.

Baseball was originally invented with middle and upper-class professionals in mind, a gentleman’s game and bonding ritual. But it wasn’t too long before testosterone took over and winning these games became the priority. “Ringers” — highly skilled (and surreptitiously paid) athletes outside the intended social circle — began to infiltrate ball clubs. Eventually, the façade of amateurism made way to the first professional teams, beginning with the Cincinnati Reds in 1869.

Baseball historian David Q. Voigt, in his opus America Through Baseball, writes that the game was “a primary vehicle of assimilation for immigrants into American society and a stepping stone for groups such as Irish-Americans…” In fact, that Irish influx helped create an anti-English backlash that reduced the popularity of cricket in the U.S. and helped solidify baseball as the “national game.”

According to Stephen Reiss, a history professor at Northeastern Illinois University and author of Touching Base: Professional Baseball and American Culture in the Progressive Era, the Irish came to America “with a manly athletic tradition and quickly became avid sports fans and athletes in their new country.” Unlike other immigrant groups, who demanded their children eschew frivolous pursuits (such as sports) to concentrate on getting an education, many Irish families encouraged their young men’s interests in pursuing athletic careers, grateful for the additional source of income.

Unfortunately, the anti-Irish, anti-Catholic sentiment prevalent in the mid-1800s carried over to the ballfield. Irish players were considered as rough, boisterous rabble, unwelcome in the gentlemen’s game. But as Benjamin G. Rader in Baseball: A History of America’s Game notes, by the end of the 19th century “the uninhibited, clamorous, working-class ethnic culture from which [Irish players] originated spilled over onto the diamond. Less self-restrained than the old-stock Protestant players, the Irish brought with them…far more physical and emotional expressiveness.”

This stereotype carried over into baseball, which had lost its pastiche of gentility. The new breed of athletes was loud, and aggressive, and frequently displayed anti-social behavior. Boarding houses and hotels where a visiting team might stay dissuaded the use of their facilities by adding “No Ballplayers” to whatever other prohibitions they had (such as “Irish need not apply”).

But by the 1880s, Irish immigrants and first-generation Irish-Americans made up between 33 and 41 percent of professional rosters, depending on which source you use. These numbers declined over the next 30 years as German- and Italian-American players became more prevalent. Of the more than 16,000 players to appear in the major leagues since 1876, 38 were born in Ireland while hundreds more have been of Irish descent.

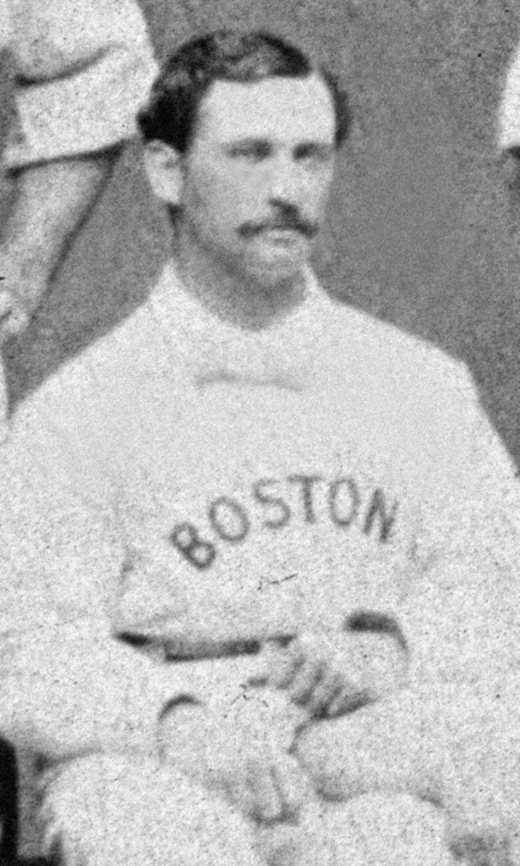

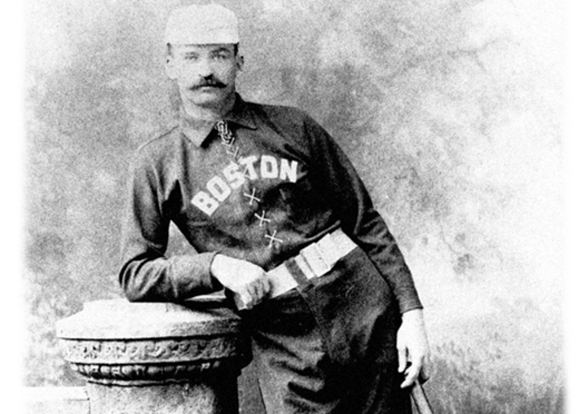

Andy Leonard was the first Irish-born major leaguer. Born in County Cavan in 1846, he made his debut with the Washington Olympics of the old National Association just before his 25th birthday. He played more than 500 games with the Olympics, Boston Red Stockings, Boston Red Caps and the Cincinnati Reds, retiring with a career batting average of .299 while playing in both the infield and outfield.

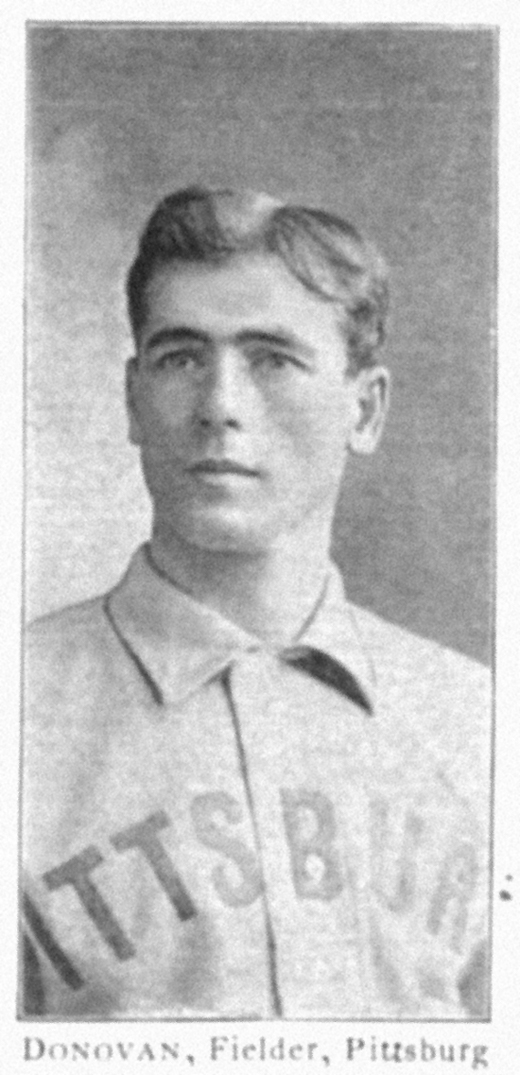

Other native-born Irishmen who enjoyed relatively lengthy careers include Patsy Donovan, born in County Cork in 1865 and owner of a lifetime .301 batting average and more than 2,200 base hits; “Dirty Jack” Doyle (Killorglin, 1869), who drove in nearly 1,000 runs to go along with his .299 average over sixteen seasons; Tommy Bond (Granard, 1856), who won 234 games; and Tony Mullane (Cork, 1859), winner of 284 contests.

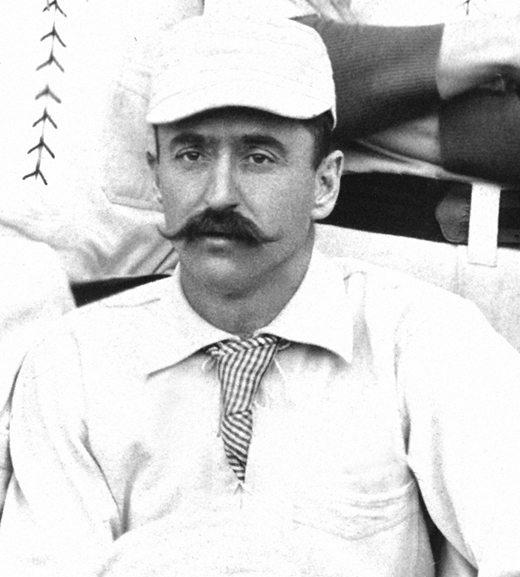

Michael “King” Kelly was a first-generation Irish-American baseballist and one of the first “superstars” of the game (although such a term had yet to be invented). He was a charming, handsome fellow with a personality that augured well for him away from the diamond. One year he made $2,000 for playing ball but another $3,000 for permission to use his photograph for the team publicity. He toured the vaudeville circuit in the off-season, augmenting his income in excess of $5,000. A song written in his honor — “Slide, Kelly, Slide” — was one of the most popular tunes of his day. He batted over .300 and used his superb running speed to steal at least 350 bases (records from those days are somewhat incomplete) during his 16-year career (1878-93). All this earned Kelly a place in baseball’s Valhalla, the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

The Baltimore Orioles were the bad boys of baseball in the late 1800s, doing whatever it took to win. In those days there was only one umpire to keep track of all the activity and he certainly had his hands full. The Orioles would often trip opposing base runners, grab at their uniforms or hide balls in the field to use in case of emergencies. Among the Irish contingent on that team were John McGraw, Wee Willie Keeler, Big Dan Brouthers, Hugh Jennings and Joe Kelley, all of whom are enshrined in baseball’s Hall of Fame. Ned Hanlon, the Orioles’ manager, is credited with refining many of the tactics and strategies that have become routine, such as the hit-and-run, the squeeze play and the “Baltimore chop.” He must have shown inspiring leadership since several of his crew went on to manage after their playing days came to an end, including McGraw, Kelley, Jennings, Miller Huggins and Wilbert Robinson.

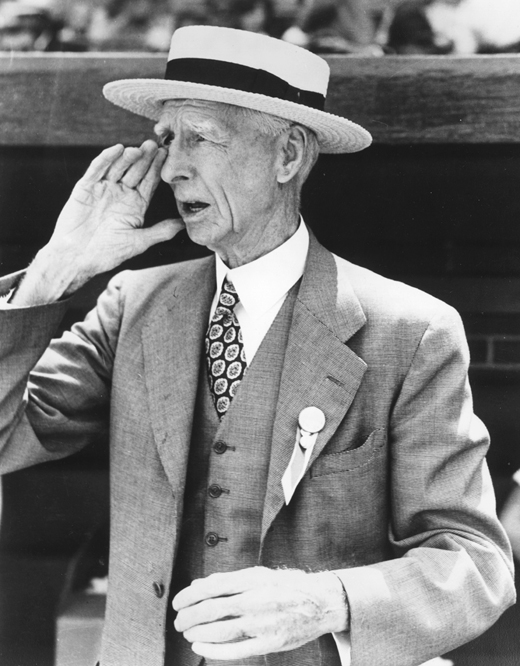

Indeed, perhaps the biggest influence the Irish have had on the game has been in the dugout. In the first quarter of the 20th century, eleven of the sixteen major league managers had Irish roots. Principal among these were McGraw and Connie Mack, both sons of Irish immigrants. Mack, born Cornelius Alexander McGillicuddy, banged around the minor leagues before catching on as a catcher with the Washington Nationals in 1886. He retired as an active player in 1896 and five years later acquired the Philadelphia Athletics, which he led as both manager and owner until 1951. Known as the “Tall Tactician,” the mild-mannered Mack never wore a uniform while managing the Athletics. He wasn’t allowed on the field so he used his son Earle, as his designee.

In contrast, McGraw, who lost his mother, stepsisters, and three sisters to diphtheria when he was twelve, and took to the road when he was 17 after a fight with his Irish immigrant father who had a propensity for drinking and brawling, was as feisty as they came. He started in baseball as a $40-a-month ballplayer and joined the New York Giants as player-manager in 1902. He led them to ten league championships and three World Series victories over the next 31 seasons. In 1901, while still with the Orioles, he denigrated Mack’s Athletics as a bunch of “white elephants.” Mack defiantly incorporated a white pachyderm in his team’s new logo and the A’s won the pennant that year.

It is somewhat fitting that Mack and McGraw occupy the top two slots in all-time victories, with 3,731 and 2,763 wins respectively. Mack also lost more games than any other manager, with 3,948; McGraw drew the short straw in 1,948 contests.

Other Irish-American players of note: Mickey Cochrane, a catcher for the Detroit Tigers and Philadelphia Athletics, who was a winner both as a player and a manager;

Roger Bresnahan, a team-mate of McGraw’s, who invented shin guards for catchers and worked on early versions of today’s batting helmets;

Dan Brouthers, who at 6’2″ and well over 200 pounds, was literally a giant among men. He was the game’s “Babe Ruth” until the real Ruth came along;

Big Ed Delahanty, the best of five brothers to play professionally and a legendary figure because of the mysterious nature of his death, ostensibly in a fall from a moving train near Niagara Falls;

James Galvin, an extraordinary pitcher (361 wins) who earned the nickname “Pud” for “turning opposing batters into pudding”;

“Sliding” Billy Hamilton, one of the fastest men to ever play the game and perhaps the best player in the 1890s;

Tim Keefe, another 300+ game-winner from the 19th century;

Joe Cronin, a hard-hitting player/manager for the Washington Senators and Boston Red Sox who later served as president of the American League;

Joe Kelly, another member of those mischievous Orioles, who loved to hide extra balls in the high outfield grass to use in case of defensive emergencies;

“Iron Man” Joe McGinnity was known for his durability on the mound, but his nickname actually came from his off-season job — working in his father-in-law’s iron foundry;

Bid McPhee, an outstanding defensive second baseman who set the standard for future players at the position;

Kid Nichols, one of the top pitchers of the 1890s. He led the Boston Beaneaters (later the Atlanta Braves) to five pennants, winding up with 361 career victories;

“Orator” Jim O’Rourke. One legend has it that O’Rourke, a graduate of Yale, declined to drop the “O” as a prerequisite for signing his contract with the Protestant-owned Boston Red Stockings. “I would rather die than give up my father’s name,” he replied. “A million dollars would not tempt me.”

Ed Walsh, the last pitcher to win 40 games in a single season;

Mickey Welch spent the majority of his career with the New York Giants and won more than 30 games four times in his thirteen seasons;

Joe McCarthy made his name as manager of the powerhouse Yankees of the 1930s, winning six American League championships and six World Series between 1936 and 1943;

Bill McKechnie wasn’t much as a player in his 11-year career, but he earned his stripes as manager of four National League clubs over 24 seasons;

Jocko Conlon and Bill McGowan, long-time umpires who added color and integrity to the game;

Nolan Ryan, a more contemporary ballplayer who retired in 1993 after blowing away batters for over twenty years, finishing with a record for strikeouts (5,714) that might never be broken.

These gentlemen have one thing in common besides their heritage: they’re all members of the Hall of Fame.

No doubt Mark McGuire will soon be added to this list. The Bunyanesque slugger broke the single-season home run record in 1998, in an exciting battle with Sammy Sosa. The duel helped win back fans that were still smarting from the devastating strike of 1994-95. McGwire retired in 2001 with 583 home runs, good for sixth on the all-time list.

Derek Jeter, the perennial all-star shortstop for the New York Yankees, may also wind up with a Hall of Fame plaque; Jeter’s Irish heritage comes from his mother’s side.

Jeter’s cross-town rivals, the New York Mets, host several games at which they pay tribute to various ethnic groups. One of the livelier gatherings is Irish Heritage Night. Baseball in general should do more to remind fans of the great debt owed to the McGraws, the O’Rourkes and the Hanlons, who helped develop the game from small-time rural contests into a billion-dollar industry of the 21st century. ♦

Leave a Reply