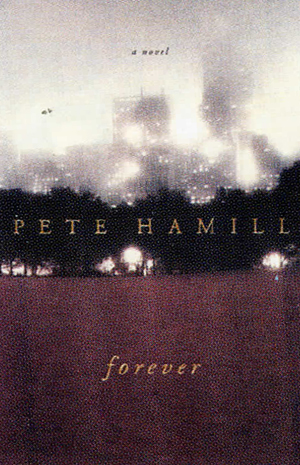

This excerpt from Pete Hamill’s novel Forever takes place aboard a ship bound for New York.

℘℘℘

Holding a lantern, Mr. Partridge showed Cormac the next deck, and for the first time he saw the deck of the emigrants. They lived in four rows of bunks hammered together from rough plank, with no bedding supplied by the ship, jackets serving as pillows, coats as blankets. All slept in their clothes. The only natural light came dripping down from the fore and aft hatchways, but in the orange light of Mr. Partridge’s lantern, faces peered at them in a wide-eyed way. A few old men stared at the deck, blinking, ignoring the light. Strapping young men tried to stretch, smoking from short earth-colored clay pipes, nodding, smiling, or throwing hostile glances at the visitors. Children scampered about, up one aisle, down another. Many women were seasick, their faces ghastly with the loss of control, and the air was stained by a mixture of vomit and shit. On that deck, they were all Irish.

A moment of silence greeted Cormac and Mr. Partridge and was broken by a man crooning in Irish from the shadows, a melody Cormac knew, a melancholy tale of a lover’s journey. Then dozens of them joined in, and someone produced a fiddle and began to play in counterpoint, and all of them were shaking heads about the loveless land that was vanishing behind them and then smiling about the magic land to which they were going. The land ahead, of course, was Tir na Nog. The land of eternal youth.

“They have no idea how far it is,” Mr. Partridge whispered. “They think crossing the Atlantic is like crossing the River Shannon. The educated ones know but won’t explain to the others. Afraid of what might happen, I suppose, afraid of despair, or riot. They’re almost all Presbyterians, the educated ones, fleeing the Church of Ireland and its endless bloody cruelties. But the ones singing in Irish, they’re real Irish, out of the hills and the bogs and the hungry towns. Most of them don’t speak English. And they’ve signed on as indentured servants. Poor buggers.”

He explained what an indentured servant was (for Cormac had never heard the words), and how these hungry Irish people, listening to the siren call of America, signed on. They pledged five to seven years of their lives, without pay, without schools, five years of labor for English planters in America, in exchange for their passage. They would be free of heartbreaking Ireland and the terrible hunger. The English were, of course, happy to see them go, particularly the Presbyterians, who were gifted at making trouble. In America, they’d work in the earthly paradise, and when the passage was worked off, they’d be free to live their lives.

“But except for knowing they’ll someday be free, they’re no different from the poor, bloody Africans. They’re owned, lad. D’ye understand me? Other men own them. And in America, the men who own them, who have them under contract, those men sell them, just the way they sell the Africans. Although on this ship, the Africans are in even worse shape than the Irish.”

“What Africans?”

“Come.”

With the fiddle playing behind them, and the Irish joining in their sad, hopeful song about Tir na Nog, Mr. Partridge moved down still another ladder, with Cormac behind him, descending into the bottom level of the ship. He told Cormac to mind his head, since the space was cramped, only four feet of room. In the lantern light Cormac saw the grillwork of a jail and beyond the timbered grille, the glistening forms of men. Black as coal. Black as midnight. Eyes stared at him and at Mr. Partridge. Eyes yellow in the light. Eyes sullen. Eyes angry. Mr. Partridge raised the lantern, said a polite hello (to no reply), and told Cormac that there were thirteen men in this fetid place, with its smell of swamp (as Cormac remembered the rotting Irish corpses in the river that made Thunder change his course). And there’s one woman, he added (citing the captain himself as his authority), a woman who claimed to be a princess. In the far corner of this small prison, there were lumpy shapes covered with rough blankets. Cormac thought: One of them must be the woman.

“It’s a dirty business,” Mr. Partridge said. “But it’s England’s favorite business because it’s so easy. They buy Africans for three pounds from the Arab traders and sell them in New York for fifty pounds. So you’re looking at, what? Seven hundred pounds worth of living, breathing merchandise, lad.”

The pieces of living merchandise looked at Cormac, breathing lightly but saying nothing, asking nothing, expressing nothing except some muted, wordless, seething anger. In his mind, Cormac saw the shop on the Belfast quays, the shop of the slave trading company, and the earl’s face, and wondered if these human beings could be his property.

“Let’s get some air, lad,” Mr. Partridge said in a desperate way, holding a handkerchief to his nose.

They retraced their steps to the main deck. A clean wind was blowing, filling the sails and the swishing sound of the ship was louder as it cleaved through the Atlantic waters. But the clean wind couldn’t scour from Cormac’s mind as the images of the Africans and the Irish, jammed on their separate levels below his feet. The words of his father’s letter rose in him: I hope you will never oppress the Weak, that you will oppose human bondage in all its guises, that you will bend your Knee to no man. ♦

© Little Brown Publishers. Reprinted with permission.

Leave a Reply