Pete Hamill, not unlike Cormac, the hero of his novel Forever, lives in the Five Points area of downtown Manhattan where the streets teem with immigrants just as they did back in the founding days of the city when Hamill’s hero emigrates from Northern Ireland. (On the day of our interview Hamill had yet to see Gangs of New York which is also set in the Five Points — see Editorial).

Hamill’s apartment, where we meet on the day after Thanksgiving, is a spacious loft filled with artwork and books that reflect his interests, and those of his wife, Japanese journalist Fukiko Aoki. There is also a distinct Mexican influence. If New York City is Hamill’s first love, Mexico is definitely his second. It’s where he went to university on the GI Bill and studied to be an artist. This passion is reflected in his book on Mexican painter Diego Rivera, but New York is his town. It is the subject of many of his newspaper articles and his novels.

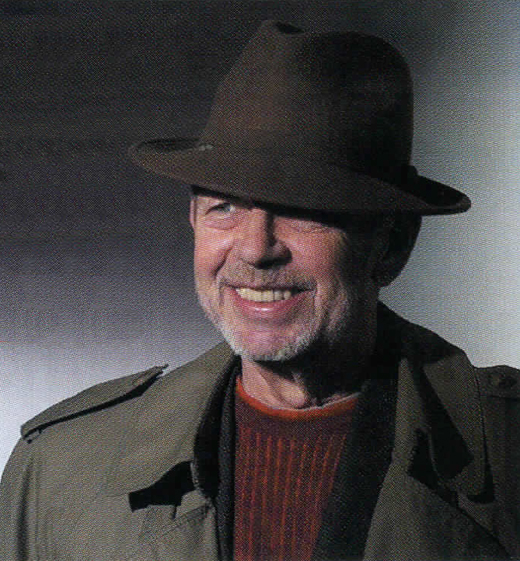

Born in 1935, the oldest of seven children to parents from Belfast, Hamill left school at 16 to work in the Brooklyn shipyards, then joined the Navy and educated himself not just by reading but by traveling.

He began writing for the New York Post in 1960, and has the distinction of having been editor-in-chief of both the Post and the New York Daily News. His work has been published in every major magazine including Esquire, New York, and the New York Times Magazine, and he is currently on the staff of the New Yorker.

Aside from his journalistic work, Hamill is also the author of eight novels (his 1997 novel Snow in August is enjoying renewed interest since being selected by Governor Bill Owens as the focus for Colorado’s “One Book, One State” program last year) — and a best-selling memoir, A Drinking Life.

Hamill, not unlike the hero of Forever, has mixed with many of the leading figures of his time, and dated beautiful women, including Shirley MacLaine and Jackie Kennedy. (He also wrote Why Sinatra Matters, an extended essay on the late singer whom he knew). But it is to his wife Fukiko to whom he dedicates his latest work.

A few blocks from Hamill’s apartment is the old Tweed Courthouse where Hamill was on the morning of Sept. 11th, at a board meeting of the Museum of the City of New York. His novel finished just the night before, he is looking forward to a celebratory luncheon with Fukiko.

In ten minutes the world changed and Hamill spent the next weeks writing about the aftermath of the attacks for the Daily News and other publications, and then retreated to Mexico where he realized that he had to rewrite his novel. “I couldn’t do a novel that starts in 1740 New York and leave out the greatest calamity in the city’s history.” The process took a year, as Hamill went over the manuscript “note for note.” Several factors already built into the story, one being that one of the main characters works in the Twin Towers, allowed him to take from his own experience of the attack and weave it into the novel so that it now ended on Sept. 11, 2001.

Hamill is currently working on another novel, and on an art book about the illustrator Thomas Nast who as well as leaving us the image of Santa that became universal, penned all those anti-Irish cartoons and was particularly scathing of Tammany Hall’s Boss Tweed.

Patricia Harty: Where did the idea for the novel Forever come from?

Pete Hamill: I was doing a book on Diego Rivera, the Mexican painter. And he has a wonderful mural — one of his last good paintings — it was done around 1947, and I had seen it in the 50’s when I was a student in Mexico, and I saw it again and it has all these characters from his own life — and I said “I’d love to do a novel like that.” You know, where you could have the heroes and villains and have as much affection for the villains as the heroes, because without the villains, there’s no heroes. And I thought “How the hell could I write a novel like that?” and the answer came almost immediately: “What if he could live forever?”

And you set it in New York City.

I think what I tried to do is answer the questions that we’d ask ourselves: If we could live forever, what would we do? We’d probably sit down and say, “You know, I’d like to learn about ten languages. I’d like to read Homer in the original. I’d like to truly know a place.” And if you had to be that person, there’s only one place in the world where you would want to be and that’s the city — the city is a living organism, so it’s always changing — it’s changed by men and women and everything else — it’s always a different place. And so if you had to live forever, to live in the city, as compared to Winesburg, Ohio, would be a consolation.

The scene of Irish indentured servants on the same ship as African slaves is poignant.

Yes. On the same ship. The reason they were buying the Irish indentureds down on Wall Street was to transport them South where they thought there were now too many blacks — they wanted to get more whites, so they sent a lot of the Irish down there.

And then, later in the century, when the cotton gin was invented just after the Revolution, slavery got so institutionalized, it took a war to break it apart. The only guy who stood up and said “Slavery’s a curse” was Franklin. There was a betrayal of the blacks who fought in the Revolution. The Tories did the same thing. They’d promise freedom to the blacks when the war ended, but on Evacuation Day, they sailed out of the harbor and took a bunch of them to Jamaica, where they were turned back into slaves.

I’d love to see a revival of Evacuation Day on November 25, when the last British ships sailed out of New York. It was a big holiday for a century, but all the anglophiles got rid of it at the end of the 19th century. They should revive it, because everywhere in the world there is trouble right now, the Brits were there first. In India and Pakistan, Israel and Palestine, Cyprus — who was there first? Who was the cause of it all?

Do you think Irish Americans will be surprised at the parallel history of the Irish and the Africans?

At that and other things — not as Irish people but as Americans. For example, you couldn’t be a Catholic in this country or in any British colony. There was no Catholic Church until St. Peter’s opened downtown after the Revolution. Most American don’t know that.

I think they might be surprised to know that there was once a New York where there was no segregation. The Irish, the Africans and the Jews all banged up against each other and married each other — many of them in the Five Points.

And maybe they will be surprised at the story of John Diamond [Irish] and “Juba” Lane [African], having dance-offs in the Five Points and inventing tap dance. Dickens happened to stop by one night and saw Master Juba and wrote about it in his little book American Notes. One of the few things he liked about New York. And that’s how it ended up in Albert Hall.

Why do you think this common history is not more widely known?

It’s not taught. Part of the problem, for thirty years at least, has been with African American scholars who actually try to segregate black history, when in fact it was much more mixed in places like New York and New Orleans and San Francisco. We’re not individual metals — we’re an alloy. That’s why in New York by the Saturday after September 11, the place was working.

You have been quoted as saying, “It’s not the falling down, it’s the getting up.”

We all get knocked down in life. If you don’t, you’re living as a hermit or something. It’s when you get up — how long it takes you, and what you do after you get up that’s important. And I was never prouder of being a New Yorker than that week after September 11. I saw all these Chinese women who work across the street in the sweat shops — when the cops and National Guard began to let pedestrians come through they streamed into the area, not because they said, “We want to show Bin Laden,” it was more like “I’ve got to feed my kids.” These are unbelievably tough — in the best sense — people. And that’s the mixture you see here all the time. I walk through Chinatown and I know it was Irish. I know that Mott Street was where the upper class Irish from the Five Points lived. And then the Irish were moving, and the Italians had it. And now it’s Chinese and that’s really New York.

So it’s a city that understands — its character is formed by people, by immigrants who had to give up a country — a language. People know how to get over things.

Boss Tweed comes across as a sympathetic character in your novel.

He’s the key guy in the 19th century for me. To start with, he was not Irish, he was Scottish, but he understood that the Irish were the key to any kind of political power in the city.

He was a supreme Machiavellian type in the sense that he had to play the cards dealt to him. Machiavelli’s great lesson was you had to live in the world as it is, not what it should be, or what it might be, or what some idealist tells you it should be. And part of that for Tweed was dealing with the upstate Republicans who were infinitely more corrupt than Democrats in the city. A lot of the stolen money — Tweed didn’t end up with much money when he died in prison — went to paying off the Republicans.

Let’s put it this way, if it was two in the morning, I’d rather be sitting up late with Tweed than any of the people who deceived him, and certainly, more than any of the politicians right now — imagine having to sit up all night with George Bush, or Tom DeLay, or Al Gore! I’d rather be with Tweed, because he’d make you laugh. He’d be entertaining. And he would tell you how things worked.

He was the last of an old way of doing things. The new guys were totally different. They knew how to avoid getting arrested — they knew how to do it legally.

So, I wanted to capture Tweed — though he’s not a major figure in the book, he sort of represents the 19th century — up to about 1875. Then you have the beginning of modern capitalism — for better or worse.

You’ve also written on the importance of JFK’s election for the Irish.

He was important because you had to get rid of that last vestige of the 19th century, which was the exclusion of Catholics from political power — not from politics, but from real power. As in the Al Smith case, although Al Smith was not all Irish — he was part Jewish, part Italian — he was the alloy before we ever thought about it that way, but he was opposed because he was a Catholic. And then, after Kennedy got elected, that was the end of it.

To me that was getting rid of the last prejudices in terms of the social acceptability of the Irish. And what it did was make possible Joe Lieberman running for office with very few people making much of a point about his Jewishness.

I do think that the acceptability of African Americans has lagged behind, and it’s the only remainder of the 19th century that has to be breached on a national level.

Some would say that there’s this dynamic now that both the Irish and the African Americans are deserting the Democratic Party

I don’t think of it that way because to some extent, there is no Democratic party anymore, in the sense of it being a [political] party, rather than a kind of sentiment, or a line on the ballot. It’s not a functional party, in the sense that a political party should be a buffer between the government and the people. It should be there to say what’s needed. That’s what Tweed did. You know, Albany wouldn’t give us water in the Five Points until Tweed paid them off.

So I think that what you’re seeing with African Americans and Latinos, particularly — more with Latinos — is that they are ceasing to be Democrats. They’re walking away from a party that’s not there anymore — that doesn’t provide services, help you get jobs, help you get your kids into certain schools, or help you with a bail bond if your kid’s in trouble.

Part of that goes back all the way to Roosevelt. Once the New Deal came and began to provide services from the government — welfare and social security — they took away some of the things that the local Democratic leadership used to provide. A supreme irony.

So there’s an interesting theory fight now about whether the parties will reconstitute themselves in some way and create a mass base again, rather than being representatives for certain interests — the trade unions and so on. You may go to the big dance at the Democratic Club, or the Fourth of July picnic, but you don’t get a sense that there’s a vital involvement of local people in politics.

What are your thoughts on the current crisis in the Catholic Church?

First of all, I hope in our anger, we don’t throw out the basic, fundamental standards of proof. I’m sure if Paul O’Dwyer were alive he would be a defense attorney for an accused priest.

Clearly, Catholicism — and I’ve seen it a lot in Latin America, where it does really good work — is supposed to help the poor. But I think that once this Pope is gone, they have to give serious thought to reforms in the Catholic Church. You can’t have a bunch of guys all living together in some bizarre way in the middle of the modern world. They have to allow priests to marry, they have to allow women to become priests. If they did that, and started by reforming themselves to take the hypocrisy or the impossibility out of it — there would be a lot of good people that would be attracted to being priests.

I’m not a believer, particularly, but they always say “There’s no such thing as an ex-Catholic, only retired Catholics,” because it gets into you when you’re a kid. I love the art the Church made and the music. When I was writing this novel, I listened to a lot of Gregorian chant — not because it reminded me of the church, but because formally it reminded me of how sentences should flow. So the music, the art, and the architecture is in addition to the word, not a detraction from the word. And I don’t think that should all go away and be turned into a museum.

What would you say was the key to your success in life?

I think the key thing in my life was my mother, because my father – whom I loved – was much more an Ulster man in his inability to express certain emotions. But my mother was better educated – she’d finished high school, which was a triumph for any woman in those days, but for a Catholic woman in Belfast it was amazing. And because her father had gone to sea, she understood that there was a wider world out there, which is why she loved New York when she got here.

She loved it because of its differences. And because of the way she was, I had that sense that everything was possible. It wasn’t absurd to say “I want to be a painter.” It was kind of nutty to my father. He thought that once I got that job in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, a civil service job, I should stay there for life. But she thought that the whole point of this place was that you were not a prisoner of what your father or your grandfather did.

But the timing was important too, because I was ten when World War II ended, and that first five years after the war, New York was a wonderful town. All the GI’s were coming back, the ball players were coming back — there was a sense you could do anything. You could play for the Dodgers or you could write a book, be a lawyer, be anything. And the other aspect of it right after the war was that the GI Bill began to change the world that existed in 1940. And that meant that the sons of factory workers could go to Yale.

If there’s a third factor, and a lot of my fiction is about this — it’s the fact that I grew up in the last American generation shaped before television. So that the things that stimulated the imagination came from different sources: the movies once a week, the radio, which is much more like reading because it’s words and you create these little pictures actively in the mind, and reading. So there was some sense of language being an important part of growing up.

How did you become a journalist?

When I got back from the Navy, I applied to Columbia [University] and they rejected me because I never graduated from high school. But I could draw too, so that’s what took me to Mexico City to study art, and to the School of Visual Arts in New York.

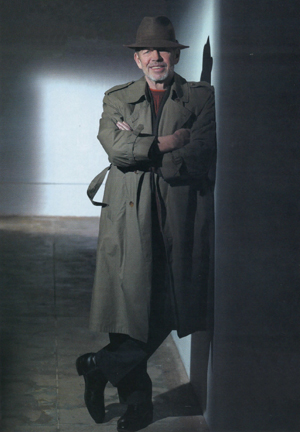

But I still had this notion of being a newspaperman. I loved reading newspapers. I started when I was ten or eleven on the comic strips, and I found my way to the rest of the paper — and I loved it. I also had these notions about being a newspaperman that was shaped by the movies — Roman Holiday with Gregory Peck and Audrey Hepburn, mixed in with An American in Paris and Joel McCrea in Foreign Correspondent — the sort of trench coat guys. But my start in the business came about entirely by accident. I wrote some letters to the New York Post which were published around late ’59, early 1960. And Jimmy Wechsler, who was the editor, was also in charge of the letters page because the Post had the world’s smallest staff. And he asked me to come in, and said, “Have you ever thought about becoming a newspaperman?” I said “Yeah.” He says, “You want to try it?” I said, “Yeah.”

I kept the day job at an art studio on 46th Street and I worked nights at the Post, when it was at 75 West Street, a couple blocks below what became the Trade Center. And there were some amazingly good craftsmen on a very small staff, so that I was able to do two or three stories at night, and I loved it more than anything I’d ever done.

To start with, there were seven New York newspapers so there was a lot of competition. Local television was still not quite there. Color television hadn’t happened yet. Nobody got paid enough money, that came later. But there was a sense of fun in the business. The newspaper helped put me in neighborhoods like Harlem, where there was a music scene. There was no blue-eyed-devil rhetoric or anything at the time, it was a lot easier to just go.

And Robert Wagner was mayor, so nobody cared about politics, and Eisenhower was president, and who cared? You know, politics — you didn’t do things because somebody was president. You did something because Jackson Pollock just walked in and threw a stool at somebody.

How did you meet Jackie Kennedy?

At the funeral for Bobby on the train, going to Arlington. I was there with Jose — Jose Torres [boxer]. I got to know her later.

Is that something you’d ever consider writing about?

No. It’s not just her. I wouldn’t talk about anyone I had a relationship with. I always liked that word “cad.” And I don’t think you should go around yapping. Each relationship — if it’s of any value at all — teaches you something.

Is it true that Bobby Kennedy had a letter from you urging him to run which was in his pocket when he was shot?

Oh, I don’t think so. Not when he was killed. I did write him a letter from Ireland, right after the Tet Offensive because my brother John got wounded. Saying that “You’ve got to do this.” I know that he did show that letter to different people.

I don’t even have a copy of it. The arguments in it, which were very emotional, and unpolitical in a sense – while I don’t think they were decisive, did have some effect on him – from everything the people around him told me – from Jeff Greenfield and Adam Walinsky and those guys. And he did, when he decided to run, send me a telegram saying, “I’ve taken your advice.” I did work for the campaign, briefly – for a couple of weeks – and didn’t like that part of it. He’s the only politician, at the time, I could’ve imagined working for. And Paul O’Dwyer later.

But, he did come to California. I was there at the Ambassador Hotel with him [when he was shot]. I never got that close to a politician again. I was close to Paul O’Dwyer but I’d never thought of him as a politician. I thought of him as a counselor for the defense.

That was the only time, after Bobby Kennedy got shot, I’ve ever had a writer’s block. I couldn’t write all that summer. I was living in California, Laguna Beach, with my then wife and my two daughters. And when all the hoop-la was over, we took a long trip into Mexico, and then back into Texas, where I had some friends in Austin, and back to New York, and then I saw Paul and he said “For Christ’s sakes, writer’s block? You’re too young to have a writer’s block.” And I said, “He’s probably right.”

And so I started working again, and I did some work for him. I was not really on staff or anything, but I wrote a few speeches, which he cheerfully ignored most of the time, being a man of good sense.

But 1968 was a strange year. I ended up covering the convention for New York Magazine, and the Olympics in Mexico, where a whole lot of people got shot just to put it on. So it was hard to get away from anything that year, starting with Martin Luther King’s assassination in April.

But the thing with Bobby, really — it still unsettles me. I’ll be watching television and they’ll flash on something about Bobby and I’ll feel it again. The same with Jack.

I wouldn’t watch the RFK docudrama or anything like that because I don’t want to dwell on it. It’s a long time ago. But it’s still disturbing because I really think the country would have been different. There’d have been no Nixon, no Watergate, you know, all kinds of things. It would’ve been different. I think the war would’ve ended a lot earlier, with a lot fewer deaths of Americans and Vietnamese. That’s what he wanted to do. And I think it was doable. Particularly after the Tet Offensive. What a year. The Tet Offensive in February, King in April, Bobby in June.

I don’t think it ever gets as bad as ’68 was. There was a real sense of society unraveling, of things being out of control. And we could learn the lesson of that, although it’s been cheerfully, sort of, dismissed now. But we should try to know what that was about — we ran against our own basic myths. We decided to be Goliath instead of David. But the lesson obviously hasn’t been learned — the Tonkin Gulf resolution [President Johnson ordered U.S. bombers to “retaliate” for a North Vietnamese torpedo attack that never happened] that Johnson used to pursue the war was just repeated with the Iraq resolution. People should know better. Don’t give presidents unlimited power. It’s not a healthy thing.

I also think that this administration is the most right-wing in my experience. More than Reagan. Reagan talked a right-wing line in his sort of amiable way, but he never really did much about it. This is scarier, because there’s no checks and balances. Bush has got the Supreme Court, he’s got the executive branch, and now he’s got the legislative branch. He’s liable to get whatever he wants. And we’re beginning to see it now, with things that have nothing to do with Iraq, and Al Queda and terrorism, and internment camps in Cuba — it’s things like “Oh, go logging, folks. Cut down whatever you want. We’ll solve forest fires — we’ll cut down the trees.” It’s that kind of stuff, where by the time somebody comes along that puts the brakes on, a lot of damage could be done.

I don’t think they [this administration] have much respect for civil liberties, because they’re frightened. They’re little frightened guys running the country. They talk of war because they’ve never been in one. The only guy that’s been in one is Powell. At least he was in Vietnam and got shot at. All these guys ducked it. So they can be brave. They can act like it’s the Packers and the Cowboys, instead of the real world, where people get their brains blown across the road by a rocket launcher. I think they’ll discover, if they go to war, that there are some things that you can’t bomb. You’re playing with all kinds of uncertain stuff. We’ve already lost 3,000 people. And we should be much smarter about this, and we’re not. We’re not doing well at all in the war on terror. It has soldiers in charge of it, instead of cops. I’d feel much better if Ray Kelly [Police Commissioner for NYC] was running it. The French cops and the Italian cops, and the German cops are doing a pretty good job. We’re not doing such a hot job.

I never get to the point where I say “I don’t want to have anything to do with this country.” Again, as in Vietnam, you can be in opposition because you love the country. You can say, “This is a better country than that.” ♦

When Pete Hamill passed away on August 5, 2020 contributors and friends of Irish America shared their memories of Pete.

Pete Hamill

just wrote it the way it was for mine and his generation. What a gifted writer who can put into words just what happened from WW2 until Bush. It is my story also and the the Irish American experience. I disliked Breslin because he really said in print the most vile things about his own people. Hamill

can talk about our faults in a way that doesn’t demean us. I’m amazed at the gift the Irish have for the written word. Thank you Pete don;t stop writing

and boy I can imagine what he would say about Trump.lol

Thank you for republishing this wonderful interview with Mr. Hamill who understood we need to keep creating “a more perfect union.”