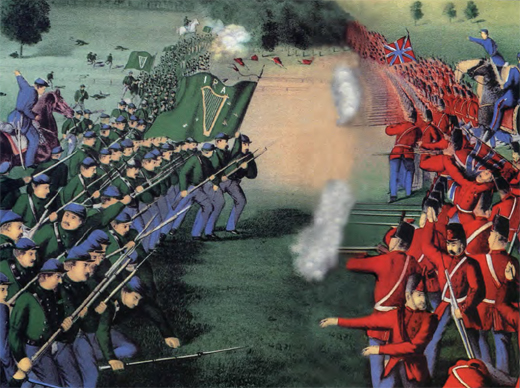

Irish veterans of the American Civil War launched attacks on Canada in an effort to win independence for Ireland.

It was 4 a.m., but the men of the 17th Regiment were wide-awake. They’d encountered no opposition crossing the water, and they expected little trouble trouncing the enemy when they came face to face. They’d been waiting for this moment for a long, long time. Jubilant cheers rang out as an Irish flag was unfurled on British soil.

It was a June morning in 1866, and the members of the Fenian Brotherhood determined to free Ireland had set off from Buffalo, N.Y., crossed the Niagara River and landed near the village of Fort Erie, West Canada.

The plan to invade Canada was developed after the Fenians concluded that Canada, transformed into New Ireland, could be used as a military base, particularly for privateers who would harry British shipping, eventually forcing Great Britain to negotiate with the Fenian leaders. They had in mind a simple swap: Canada in return for home rule for Ireland.

The consensus was that there would never be a better time for action. The Civil War had ended, and both sides had released myriad potential Fenian soldiers they had trained. Indeed, the Union army had allowed Fenian recruiters to sign up its troops while the war was under way. What’s more, the American government was selling off surplus munitions at fire-sale prices. There was also reason to believe the U.S. government would look the other way until the takeover became a fait accompli.

The original plan put forth by Gen. Thomas W. Sweeny, the Fenians’ Secretary of War and former commander of the 16th United States Infantry, was highly complex. It called for 30,000 men to stage initial attacks, taking a number of major Canadian cities within a two-week period. Sweeny believed a successful operation would attract 50,000 more Irish Americans and Irish Canadians, and a Navy could be established on the Great Lakes. The ground forces would then move on other targets.

There were problems from the start. Although the Fenians had purchased 10,000 rifles and pistols and 2.5 million ball cartridges, artillery was not available. And the number of men who joined the effort numbered a few thousand at best.

Sweeny’s decision to move ahead seems to have been a political one. The Fenian Brotherhood had undergone a split in the fall of 1865, when William R. Roberts ousted former head John O’Mahony. O’Mahony still claimed many followers, however, and his faction launched an attack on Campobello Island, between Maine and New Brunswick, on April 14, 1866. The raid was a fiasco. But it generated a number of ripples, including a fear in the Roberts faction that the Fenian Brotherhood would fall apart without meaningful action.

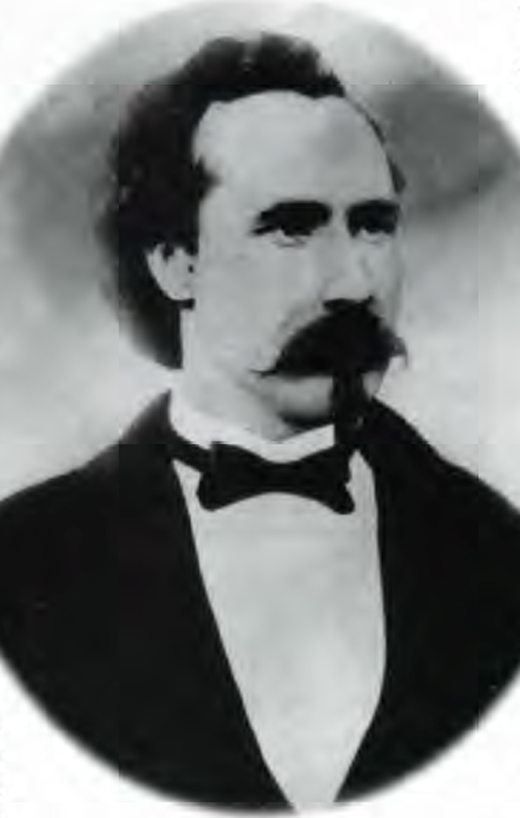

So the invasion was launched. In early May, Sweeny ordered Fenian troops in the south to head toward designated northern jumping-off points. (When queried, most told curious fellow travelers that they were heading west to look for work.) But when Lt. Col. John O’Neill and his 13th Tennessee Regiment and Lt. Col. Owen Starr and his 17th Kentucky Regiment arrived in Cleveland to report to Gen. W.F. Lynch, he was nowhere to be found. (Lynch, it turned out, was laid low with a fever stemming from wounds he sustained during the Civil War.) No one knew anything about the boats Lynch was supposed to have obtained for the assault.

Apprised of the situation, Sweeny ordered the men to head for Buffalo. Lynch’s adjutant, a Col. Sherwin, was placed in command.

But Sherwin couldn’t get to Buffalo by May 31, when the assault was to begin. So Capt. William F. Hynes, the Fenian assistant adjutant in Buffalo, put the ranking officer in charge, and O’Neill became Gen. O’Neill. He received only what he later called “a few general [verbal] instructions” from Hynes. He didn’t even have a map of the country.

The Niagara border was an ideal spot for a Fenian attack. Buffalo was a vibrant, bustling city, the tenth largest in the United States, and it had a large Irish population-an ideal place for a few thousand careful men staying in Irish-run boarding houses to blend in. The city also was a transportation hub where railroads came together with the Erie Canal and Great Lakes shipping. Moreover, on the other side of the border, there were no Canadian militiamen or regular troops within 50 miles of Fort Erie.

But although a number of groundless alarms and the comic-opera Campobello affair had led Canadians to shrug off invasion concerns, warnings of a planned crossing led to some precautions being taken. The railroad ferry was deliberately docked overnight on the Canadian side of the river. Meanwhile, Buffalo’s anti-Fenian mayor had the port closed and the warship U.S.S. Michigan ordered in.

So the Fenians headed a few miles north of Buffalo to Pratt’s Ironworks, where arms and ammunition awaited them, along with two steam tugs and four canal boats. The advance troops, under Starr, boarded the canal boats, which were towed across the Niagara River.

The regiment first stepped on British soil at Freebury’s Wharf, two miles north of Fort Erie. The immediate plans were to take over trains in the area and cut telegraph lines. But though they quickly cut the wire, the rolling stock had already been moved inland; local fishermen had sighted the crossing party and warned the railroad.

The Fenians tore up railroad tracks and partially burned a bridge over Six Mile Creek to the west, preventing any trains from moving into the area. The international railway ferry was seized, as were six men of the Royal Canadian Rifles found hiding in the ruins of the old fortress that gave the town its name.

Starr posted sentries and ordered the village reeve, or chief magistrate, to provide breakfast for the Fenian soldiers. A proclamarion by Sweeny was read, stating that the Fenians had “no issue with the people of these provinces” and that “Our blows shall be directed only against the power of England.” It also called on Irishmen throughout the provinces to join the Fenians.

By dawn, O’Neill and the bulk of the troops had arrived. Just how many men made the crossing is uncertain, but O’Neill stated in 1870 that it was no more than 600.

Fenian headquarters was set up at Newbigging’s farm, about three miles north of the village and along the south bank of Frenchman’s Creek. The creek made a good barrier against any troops heading south from the village of Chippawa, and the Fenians transformed split-rail fences into formidable barricades.

By noon, O’Neill received additional arms and supplies from Buffalo. They would be the last to get through, as the warship Michigan moved to Pratt’s Ironworks. The large force under Sherwin would never appear.

By early evening, Fenian intelligence told O’Neill that British troops were moving south along the Welland River from Niagara Falls to Chippawa, north of Fort Erie. He countered by advancing his entire force to Black Creek, still south of the Welland River. During the night, he got more news: The column at Chippawa included at least some professional infantry and field artillery. And a force of Canadian infantry was moving on him from Port Colborne to the west.

O’Neill correctly figured the Port Colborne column would travel by train to Ridgeway, a bit south of his position, and then move north to meet with the other unit. He decided to intercept the weaker force at Ridgeway. He mustered his men at 3 a.m., and they headed southwest for admirable ground: a limestone ridge running north from Lake Erie.

Altogether there were about 900 officers and men in the Port Colborne column. Its commander, Lt. Col. Alfred Booker, decided to take them off the train at Ridgeway, as O’Neill had predicted, then move north along Ridge Road, on the limestone ridge, before turning north-northwest to reach the larger Canadian force.

O’Neill gained the ridge and deployed his men about three miles north of Ridgeway, where Bertie Road intersects with Ridge Road. He ordered his reserve to a wooded height to the north, and the Fenian troops threw up breastworks along the south side of Bertie Road. A skirmish line was set up about a half mile away, where Ridge Road meets Garrison Road. The plan was for these men to fall back and lure the Canadians forward into a trap.

The Canadians advanced, reached the skirmishers and took the bait. But some Fenians began firing too soon, and two companies of the Canadians were sent in to clear the area. The Fenians’ right flank began to buckle, and the Irish began to fall back to their reserve position.

But at that point the Canadians noticed some horsemen, and, unaware the Fenians had no mounted troops, shouted to watch out for the cavalry. Booker ordered some of his men to form a square, which was the traditional way to repel horsemen but created an excellent target for infantrymen and — the Fenians took advantage of it.

When Booker realized there was no cavalry, he ordered his men back into line. But confusion quickly set in, thanks in part to hard-to-follow orders given by bugle calls. Some of the Canadian troops fell back in good order, but most simply broke and ran.

The Fenians had won the day — but they were in a precarious position. The reinforcements they expected from Buffalo had not arrived, and there was a stronger, more professional British force heading toward them. O’Neill decided to head for the ruins of Fort Erie, where he would have the option of rendezvousing with any reinforcements or withdrawing across the river.

When the Fenians’ advance guard arrived at the village, it ran into a Canadian force of a little more than 100 men and officers. The Canadians initially drove back the Fenians, but when O’Neill’s main force sent out a line of skirmishers that turned the British right flank, the Canadian officers ordered their men to save themselves as best they could.

This second victory did nothing to change the Fenians’ situation. O’Neill soon learned reinforcements could not get across the river and no other Fenian operations were under way, and decided to withdraw that night.

All started well, but the two barges (towed by tugs) carrying the troops back to the United States were stopped by an armed U.S. revenue cutter tug, the U.S.S. Harrison. The Fenians were arrested for violating the Neutrality Act. On June 6, O’Neill and his officers were fined; the enlisted men were released, having spent several days in the open barges. That same day, President Andrew Johnson issued a proclamation of enforcement of the Neutrality Act, and leading U.S. Fenians, including Roberts and Sweeny, were arrested.

By mid-June, Brigadier Gen. Michael Bums was named commander of the Fenian army still in Buffalo — some 5,000 officers and men. But he was to oversee a dispersal rather than an assault. In return for a promise to give up the invasion, the government agreed to provide the Fenians with free transportation home, and so the army disbanded.

The Canadians arrested a number of stragglers and deserters. More than two dozen were sentenced to death, but none were executed, and all but one, who died of natural causes, were quietly released by early in the 1870s.

The Fenians launched a few other attempts to invade Canada, but they were sad shadows of the Niagara campaign. The Fenian Brotherhood slowly faded away, and Irish freedom was won in Ireland, not in North America. ♦

Very interesting!

Harry Dunleavy

“The Fenian Brotherhood slowly faded away, and Irish freedom was won in Ireland, not in North America. ” A very misleading remark in an otherwise fine article, First, many would argue that Irish freedom is still very much an on-going process. Second, the “Irish Freedom won in Ireland” would not have been possible without the financing and logistical support from “Ireland’s exiled children in America”