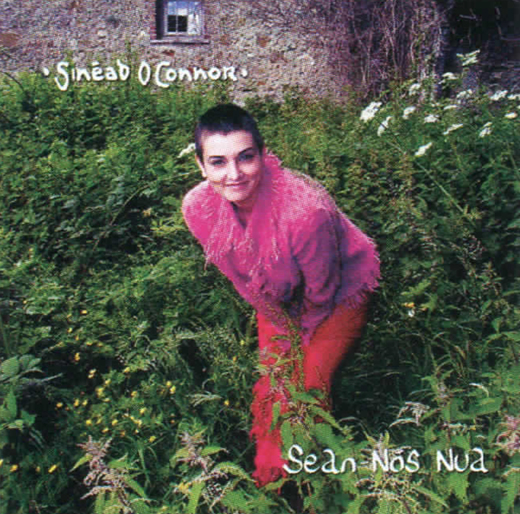

In New York to promote her new album of old Irish songs, Sinéad O’Connor talks to Bill Crandall

Sinéad O’Connor hasn’t been here since the towers fell. As a car carries her from JFK to the city, she asks the driver what it feels like without them. He says he feels lost — literally, because he used the buildings to help him navigate around town.

That night she and her fourteen-year-old son Jake stand on the balcony of their room at the Shoreham Hotel and gaze up at a neighboring skyscraper. They marvel that something bigger than that could fall.

“It’s hard to comprehend,” she says the next morning. “To imagine those falling down, it’s just…no matter whatever has been going on in Ireland, there’s never been anything on that scale.”

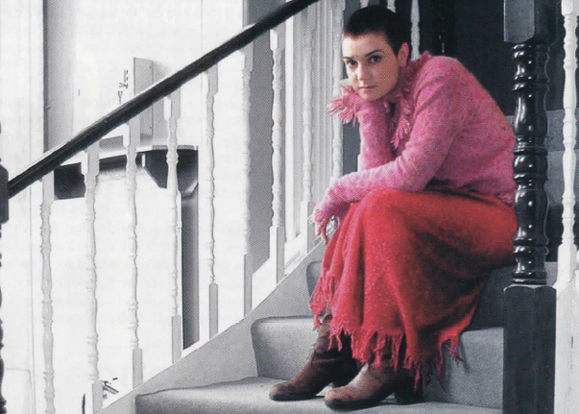

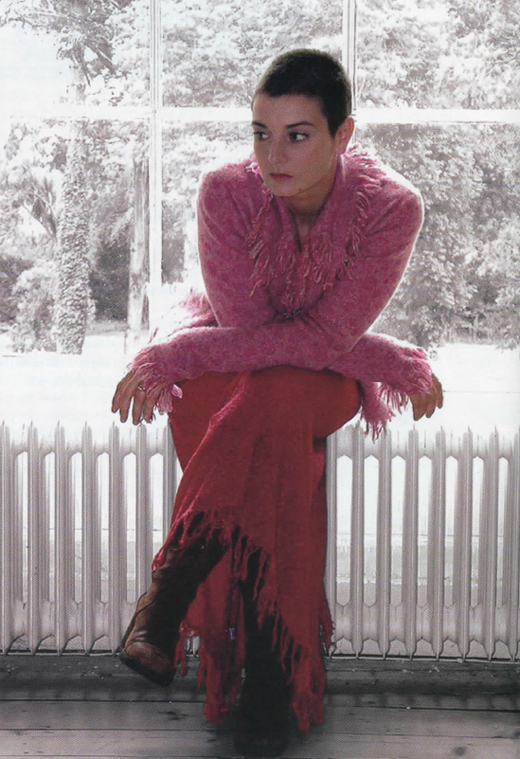

For a woman who’s often drowned out her gorgeous singing voice with bold public statements — objecting to “The Star Spangled Banner” being played before one of her concerts and tearing up a picture of Pope John Paul II on Saturday Night Live — Sinéad O’Connor is hardly an imposing figure. From behind her black crew cut and burgundy frock, the diminutive O’Connor speaks softly, smiles nervously and smokes incessantly.

After spending 16 years in London, the 35-year-old O’Connor now lives in Dublin, where she was born, along with her new husband, British journalist Nick Sommerland, Jake and her six-year-old daughter Roisin (both from previous relationships). During the past year, she’s made a musical journey home as well, recording Sean-Nós Nua (Old Style New), an album of traditional Irish ballads.

But even that seemingly wholesome pursuit may garner O’Connor some controversy, because she doesn’t exactly follow the established rules for singing these songs. First and foremost, she strives to return to the passion, the sexuality, the “rock & roll-ness” of Irish music something she says has been missing for centuries, ever since Irish culture began taking cues from the Catholic Church.

“Up until maybe fifteen years ago Ireland was pretty much a dictatorship run by the Church and their thinking,” she says. “They managed to get a hold of people through the education system, and they took the sexuality out of Irishness, out of being an Irish person, and out of the music.”

O’Connor points to beloved early twentieth-century tenor John McCormack, who was made a count by the Vatican, as the ultimate manifestation of this musical neutering process. In McCormack’s version of “The Star of the County Down,” the stricken lover does not declare “I had to scratch meself to see I was really there,” as the song was originally written, but “I was ashamed of meself.”

“He was so popular, and the Church used him,” O’Connor says. “He really enunciates the word ‘ashamed.’ And that sort of thing is what has made Irish music really uncool for younger people. Even Irish dancing is very sexless — the moves are only from your knees down.”

In addition to sexuality, O’Connor sprinkles the album with international influences. On the album’s two Irish-language songs, “Oró Sé Do Bheatha Bhaile (Oh, You Are Welcome Home)” and “Báidín Fheilimi (Phelim’s Little Boat),” Syrian and Jamaican musicians supply overdubs. Again, O’Connor has her political as well as her musical motives: “For the last ten years or so there has been this huge, sinister outcry against all these different kinds of people moving to Ireland. But if people get together musically, they can change things politically — or, if you like, make babies together, which is the best way to cure these problems, by mixing everybody up. Here, the songs are the babies.”

Sex and politics aside, Sean-Nós Nua is a strikingly beautiful collection of ballads. O’Connor’s familiarly emotive coos and wails are backed by some of Ireland’s best contemporary folk musicians: Donal Lunny (acoustic guitar, bouzouki, bodhran, keyboards), his daughter Cora Venus Lunny (classical violin), Steve Wickham of Waterboys fame (fiddle), Sharon Shannon (accordion) and Rob O’Gheibheannaigh (whistle and banjo). Even winsome crooner Christy Moore joins O’Connor for a duet on his epic ballad “Lord Baker.”

O’Connor has wanted to record this album for more than a decade — in fact, she’s had recurring dreams telling her to do so. This spring, back in Ireland and free from the obligations and limitations of a major record label for the first time since her career began, she and her ensemble were finally able to retreat to County Wicklow to fulfill her dreams.

“I’ve always loved these songs,” she says of the likes of “Peggy Gordon,” “The Moorlough Shore” and “I’ll Tell Me Ma.” “All of us in Ireland have been growing up listening to those songs. They’re as much a part of our soul as our mammy’s cabbage.”

The songs also chronicle Irish folk history. “Paddy’s Lament” tells the story of a weary man who flees the wars in Ireland only to be sent to “fight for Lincoln”; “Oró Sé Do Bheatha Bhaile” is a tribute to Grace O’Malley, the sixteenth-century pirate who battled British invaders off the west coast of Ireland; and “Molly Malone” recounts the life and death of the Dublin fishmonger whose name has been adopted by pubs from San Francisco to Singapore.

O’Connor, who studied at a psychic school during her years in London, says she can feel the spirits that inhabit these songs. “They’re real people who really existed and this is really what happened to them,” she says. “You sort of have to be a medium to sing these songs, because they’re not you, but you have to let them through you.”

And let them through her she does…unfiltered. The naked, vulnerable quality of her voice that first captivated American audiences through her 1990 Number One hit “Nothing Compares 2 U” is on full display in these renditions. Her breathing alone often makes her seem as if she is in the room with the listener. “I come from a school of singing called `bel canto,’ which means `beautiful singing,'” she says. “They don’t use notes or scales, or breathing exercises, and you sing in your own accent. It’s based on the theory that singing is just animated speaking — you say what you mean and mean what you say. If a note is hard to go for, you don’t go for the note, you go for the feeling. And I always leave in breathing; it sounds fake to take it out.”

O’Connor uses both her own voice and her awakened sense of spirituality in her role as priest in the Tridentine order, a Catholic offshoot. And, not surprisingly, her views on religion are hardly typical of most priests. “I feel that God needs to get rescued from religion,” she says. “Actually, I think God is an off-putting word, but there is something out there in all of us that we are all part of. And it does respond to the human voice.”

All of this does not mean she backs off of her role in the infamous Pope incident of 1992. “It’s something that was long ago, and it’d be nice to move away from. But I don’t want to suggest at all that I’m not proud of it,” O’Connor says, pointing to the Church’s recent sex scandal. “I am as proud of it as I am of my two children.”

And if her two children don’t quite share O’Connor’s tastes, they have certainly inherited her independent spirit. “Jake likes hard-core rap,” she says, laughing. “It’s hideous. I had to bring him to see the Insane Clown Posse, but he wouldn’t let me come to the gig, so I had to sit in a Holiday Inn the whole time. The police let off a load of tear gas and his eye was all red for a month afterwards — and he was delighted with himself…Roisin is into Britney Spears. But she’s kind of shy about it and she doesn’t like boys to know.”

That O’Connor’s family grew last year — when she married a man — surprised many, because, the year before, in an interview with Curve magazine, she declared herself a lesbian. She now rejects the label. “I guess I don’t believe there’s any such thing as gay or straight,” she says. “People just fall in love or they don’t. Love is not conditional.”

Sinéad O’Connor, the homeward-bound exile, the patriotic instigator, the androgynous wife and mother, sums up her life in one word: “grand.” And throughout all of her changes of heart, she continues to sing her soul and speak her mind, in her own unique accent. She’s never known any other way. ♦

℘℘℘

SINÉAD ON THE SONGS OF SEAN-NÓS NUA:

Peggy Gordon: “I first heard it at a party where a woman who had lost her girlfriend was singing it. I liked the delicacy of it. A lot of times when men do it in Ireland, they really blast it out. I felt it was important not to. For me, it’s a female singing about a female.”

Her Mantle So Green: “It’s about a man who comes home in disguise from the Battle of Waterloo to see his girlfriend. He says her lover is dead and says come off and marry me, just to see if she’d be true. It’s a terribly awful thing to do.”

Lord Franklin: “It’s a true story about this guy who set off in the mid-1800s to find the Northwest Passage with a bunch of his crew and was drowned. His wife spent all her life and money sending ships out looking for him.”

The Singing Bird: “To me it’s really a prayer, a meditative song. The singing bird is God, if you like. It’s a gratitude prayer, but it’s a very powerful mantra, and it has an amazing effect on the singer.”

Óró Sé Do Bheatha ‘Bhaile: “This one is taught in school and it’s all very ‘la la la’ and sweet, but it’s really a war song about a woman called Granuaile, who was a female warrior in Ireland, and quite a ballsy chick by all accounts.”

Molly Malone: “My father taught me this song. All my ancestors are from deepest Dublin City. It’s about a woman who did really exist. It’s really not just about her, but about a Dublin that is lost in time, but the ghosts are still there.”

Paddy’s Lament: “This song doesn’t judge anyone for wanting to go to war. This guy is just standing in the middle of a battlefield in his gear, looking around. I see him as a very old man, and I like that vulnerability. All he’s talking about is his concern for your safety, which is incredible.”

The Moorlough Shore: “One of my favorite songs of all time. It’s from the North of Ireland, and it’s quite a magical melody. It’s about how a guy runs away from his woman on impulse just because she tests him. He’s singing it as an old man, regretting his impulsiveness.”

The Parting Glass: “I only ever heard this once in a pub in Ireland. This woman just stood up and sang it. It’s actually from Scotland, and it was apparently the most popular good night song before ‘Auld Lang Syne’ came along.”

Báidín Fheilimí: “It’s the story of this warrior guy, Phelim, who has to escape from these people who are trying to kill him, and his boat breaks up on the shores of Tory, an island off the coast of Donegal. The song’s subtext is about not running away from yourself for fear you’ll break apart.”

My Lagan Love: “Christy Moore tried to talk to me out of doing this song because normally the way people deliver it it’s very twee. But actually it’s all about sex, so I felt it was quite important to make it very, very sexy.”

Lord Baker: “Christy was in a band called Planxty with Donal and they did this song together. It’s an incredible story about a sailor who gets locked up by the king of Turkey. It’s very similar to the Song of Solomon.”

I’ll Tell Me Ma: “It’s kind of a skipping song you would know as a kid. It’s from Belfast. There’s a tradition in Irish music where if you play a grief song you immediately play a joyous song, so we did that on purpose.”

Leave a Reply