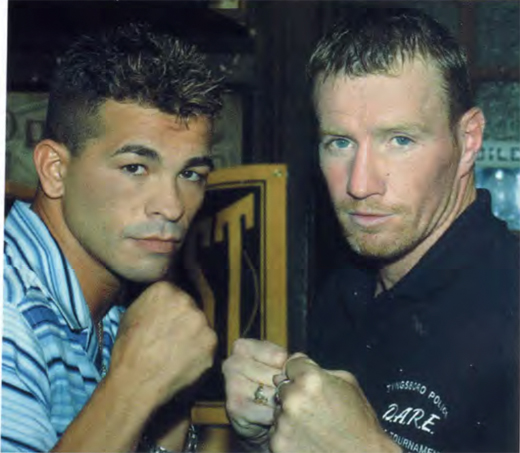

“Irish” Mickey Ward takes on Arturo Gatti again for $1.2 million

℘℘℘

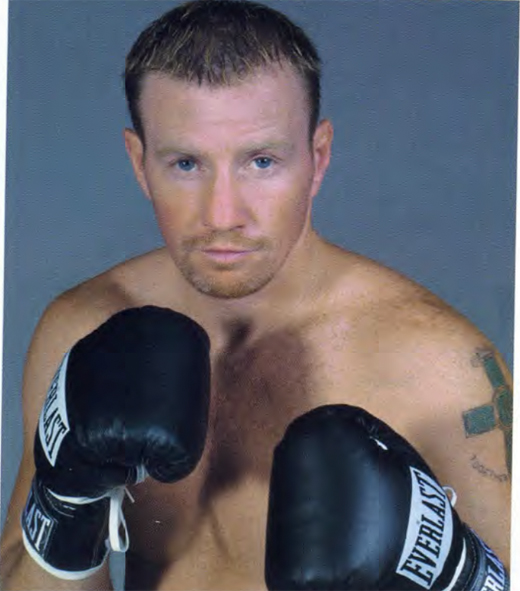

Mickey Ward is a fighter. That’s the first thing to know about him. Outside the ring, he’s soft spoken and likeable. Inside the squared circle, he’s something else.

On May 18, 2002, Ward stepped into the ring against Arturo Gatti. It was a memorable fight marked by unremitting punishment and an extraordinary ebb and flow. Some onlookers called it the best fight they’d ever seen. Others put it on a par with Muhammad Ali versus Joe Frazier in Manila for sustained action albeit at a lesser level of skill.

Ward was cut badly in round one and bled throughout the fight. In round nine, Gatti sank to the canvas from a vicious body shot, rose, took more punishment, turned the tide, and had Ward in trouble. Then Ward rallied, leaving Gatti out on his feet at the bell.

Somehow, Gatti rallied again to win the tenth round, but Ward won on the judges’ scorecards by a narrow margin.

“When I was in it,” Ward said later, “I knew it was a tough fight. I was never hurt; but I was very drained, as tired as I’ve ever been. The night after the fight, I sat down and watched the tape. That’s when I knew it was something special. That’s also when I said to myself, `These two guys are nuts.'”

Ward was born in Lowell, Massachusetts, on October 4, 1965, He is the quintessential club fighter — an honest, straight-ahead, no-frills warrior. What he lacks in talent, he makes up for with heart.

As an amateur, Ward won three New England Golden Gloves titles. He turned pro in 1985 and won eighteen of his first nineteen bouts. Then he hit a rough stretch and lost six of nine fights. In 1991, after four losses in a row, he retired from boxing. “I was burned out,” he remembers. “I had nothing left to give.”

As an ex-fighter, Ward paved streets for three years; a job he’d held part time since the age of 16. Then, in 1994, he returned to the ring and after nine consecutive wins, got a title shot against Vince Phillips (the International Boxing Federation 140-pound champion).

Early in the bout, Ward suffered an ugly cut and the fight was stopped after three rounds. It was the ultimate frustration. Mickey Ward, a warrior to the core, hadn’t been able to do his thing.

Ward received $30,000 for the Phillips fight, his largest purse at that point in his career. Other bouts for respectable money followed. Then Ward stepped into the ring against Arturo Gatti.

Like Ward, Gatti is a warrior. In the mid-1990s, he held the IBF junior-lightweight crown. Then he went up in weight and fought a series of wars culminating in a 2001 loss to Oscar De La Hoya.

The Ward-Gatti fight struck a responsive chord with the boxing public. Virtually everyone who follows the sweet science wanted to see the two men in the ring again. But what could entice them to endure that kind of punishment a second time? Money, of course.

Ward-Gatti II was a fight that HBO had to have, and the cable giant opened its checkbook wide. Mickey Ward and Arturo Gatti are now scheduled to do battle for the second time on November 23 at Boardwalk Hall in Atlantic City. Each man will be paid the mind-boggling sum of $1,200,000. To put that number in perspective, it’s almost triple the largest purse that Rocky Marciano (another Boston-area resident) ever earned.

Rematches in boxing rarely live up to the drama of a first fight, but expectations for this one are running high. Ward himself downplays the moment, saying, “It’s just another day; a hard day, but just another day at work. If I fight for the crowd and try to duplicate the last fight, I’ll lose focus.” But then he adds, “My style is no secret. I fight hard and tough whether I’m making a thousand dollars or a million. That’s the way I am. I fight as best I can with my skills. Then heart and will take over. So I’ll just go in there and fight hard again. How Arturo responds will dictate the fight.”

Unlike most boxers, Ward is experiencing his time of glory at the end of his career. He’ll be 37 years old when he enters the ring in November. As for the future, “I’m still paving streets,” he acknowledges. “Not every day, but from time to time. I’ve been doing it since I was sixteen years old, and I’ll always work; but not five days a week unless I have to. Hey, a couple of fights like this and I won’t have to pave streets anymore.”

Mickey regards his mother as the custodian of his Irish legacy. One of her grandfathers brought his wife from County Clare to Lowell, Massachusetts, and found work as a steelworker. Her other grandfather was elected to the Massachusetts State Legislature. “My mother loves talking about that stuff,” says Ward. “I’ve never been to Ireland, but I’m dying to go. One of these days, I’ll get there.

“This is a good time for me,” Ward adds reflectively. “Things are going well with my fiancée. My daughter [age thirteen from a previous marriage] is doing free. Everyone is healthy. November will be the first time I’ve had some big money to put aside. And don’t worry; I’ll be careful with it. I wasn’t born yesterday. I know that anyone who tells me they can double my money can lose all of it. They can go double their own money.”

Then Ward adds, “If someone had told me ten years ago when I’d lost all those fights and retired from boxing that someday I’d make a million bucks from one fight, I’d have thought they were crazy. But good things happen when you don’t give up.” ♦

Leave a Reply