The powerful film Bloody Sunday could teach Northern Ireland politicians a thing or two. Most importantly, that Irish Catholics and British Protestants can indeed overcome their suspicions, work together and produce outstanding results.

Bloody Sunday was produced by Mark Redhead and directed by Paul Greengrass, both British. Also on board was acclaimed Irish filmmaker Jim Sheridan and his film company Hell’s Kitchen — the force behind Hollywood Irish hits such as In the Name of the Father.

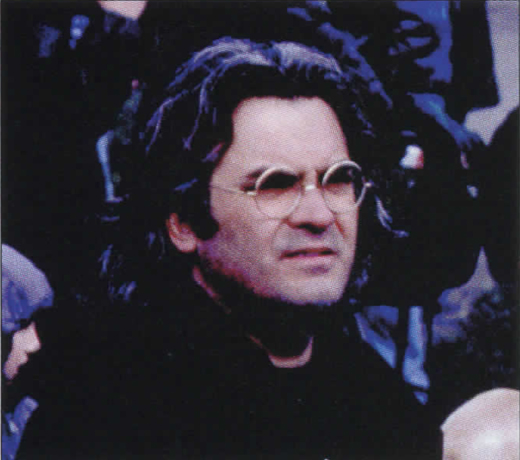

Bloody Sunday also would not have been possible without co-producer Don Mullan, who was nearly shot by British soldiers in Derry on January 30, 1972 — what came to be called Bloody Sunday.

Decades later, Mullan wrote the groundbreaking book Eyewitness Bloody Sunday. First published five years ago, Mullan’s book is based on eyewitness accounts of that fateful day in Derry, which were ignored by British authorities. Mullan’s book was ultimately instrumental in casting doubt on the official British explanation of the civil rights march which eventually left 13 dead.

Mullan himself was standing just two feet from 17-year-old victim Michael Kelly that day.

Still, Mullan is not angry that a British director was behind the camera for Bloody Sunday. In fact, he believes the collaboration — which also included using Derry residents as extras in the film — was instrumental to the film’s success.

“I can honestly say that I found Paul Greengrass and Mark Redhead to be two of the most honorable professionals I have ever worked with. They are men of the highest integrity and, at the end of a grueling process, when human flaws, irritations and idiosyncrasies can reveal the true nature of a character, I can put my hand on my heart and say that it was a privilege to work alongside them.”

Of course, there were disagreements and inevitable creative differences, Mullan says.

“But there was never any acrimony or distrust. We worked on the basis of respect and a determination to ensure our project was rooted in integrity and truth.”

Mullan did say there was some skepticism among families of Bloody Sunday victims, who were also involved in the film.

“I brought Mark and Paul to Derry where I introduced them to the Bloody Sunday families. Initially there was a trust issue. Very honestly, many of the families told them that because they were English and because of their experience with Lord Chief Justice Widgery in 1972, they had fears and reservations. They would, however, feel more secure if I was involved.”

But in the end, Mullan believes it was the cross-cultural nature of the production team which made Bloody Sunday such a successful film.

“Bloody Sunday is more properly described as a film made by two Englishmen and an Irishman with immense support from Jim Sheridan’s Hell’s Kitchen,” said Mullan. “It is the British-Irish dimension which makes this such a powerful movie.”

As for both Redhead and Greengrass, having read Eyewitness Bloody Sunday, they also knew it was critical to bring Mullan onto the movie set.

“Almost our first action on commencing the development of the film was to contact Don Mullan,” said Redhead. “Through his work, Don had developed close relations with the families of the [Bloody Sunday] dead and wounded, and he brought us together with them and helped win their support for the film. We hoped that we would be able to include as many Derry people as possible in the filming to bring the authentic voice of Derry into the film.”

Director Paul Greengrass also recalled the impact Mullan and his book had on the production process.

“I picked up a book that my colleague, the producer Mark Redhead, had been asking me to read for weeks. It was called Eyewitness Bloody Sunday…As I turned the pages of Don’s book I could see the whole scene in my mind’s eye,” Greengrass writes, in the introduction to a new edition of Mullan’s book. “Running, shouting, fighting, screaming. The thump of rubber bullets. And then suddenly — some thought almost immediately — the awesome percussive sound of British Army SLRs firing live rounds. And firing. And firing. And people dying. By the time I finished Eyewitness Bloody Sunday I felt as if I myself was crouching in terror amidst the dust and rubble of the Rossville Street barricade as the rounds echoed around that godforsaken landscape. And I knew then I wanted to make a film about Bloody Sunday.”

Perhaps what Bloody Sunday does best is combine harrowing action sequences with intimate portraits of everyday life in the North.

On the action front, Greengrass’ film is as meticulous a reconstruction of a single day as you are likely to see in any movie. The scenes are sometimes so realistic, you might think Greengrass is just one of the many amateur videographers who were there that day, who meant to record a little bit of civil rights history, but instead captured bloodshed which was condemned worldwide.

The action sequences in Bloody Sunday are shot in a herky-jerky handheld style, as if the cameraman himself is dodging bullets.

But Bloody Sunday is not simply an account of how brutal the British are, and how the North’s Catholics are simply innocent victims. Some viewers may even be put off by the depiction of British officialdom in the movie, from the officers in their barracks to the “paras” on the street with their high-powered rifles.

True, some members of both of those groups all but announce their intention to shed Catholic blood in Derry that day. But others, from a hesitant para to an officer who struggles to somehow use only “minimum force” on the crowds, can’t be dismissed as pure evil.

Greengrass said he wanted to make something like a balanced view of the events of Bloody Sunday. He appears to have done so. In the tradition of diverse films such as Medium Cool and The Battle of Algiers, political filmmaking is rarely as gripping as the best moments in Bloody Sunday.

Politician Ivan Cooper (played powerfully by James Nesbitt) is clearly the heart and soul of Bloody Sunday. As played by Nesbitt, Cooper (who was a Protestant) is an outgoing man with a common touch; he is a true believer in his cause, yet he is also able to laugh at himself. He also, Greengrass makes a point of depicting, is utterly disdainful of the IRA, and sees them as counterproductive. Cooper is a man who preaches in the nonviolent tradition of Gandhi and Martin Luther King. (By the end of the film, however, he understands that the British killings will only fill the ranks of the IRA.)

Cooper is not the sole focus of Bloody Sunday. We also see residents of Derry’s Catholic ghettoes on the evening before the doomed civil rights march. They are young lovers, babysitters, and parents out for a much-needed night on the town. Knowing what will occur the following day, the simple things about these people and their lives become beautiful, poignant and tragic.

That Mullan helped recruit Derry locals to play small parts in the film only lends greater authenticity to this film. As does the fact that there’s hardly any musical accompaniment. Greengrass’ powerful imagery generally speaks for itself. And as tough as the violent scenes in Bloody Sunday may be, even more heartbreaking is the quiet chaos of the hospital where the dead, wounded and their families await life-or-death news. It is up to Ivan Cooper to deliver the sad word to each family. It had to be some of the toughest acting James Nesbitt has ever — and will ever — do. As with most everyone else behind Bloody Sunday, Nesbitt comes through powerfully. ♦

Read Patricia Harty’s “Bloody Sunday:” James Nesbitt’s Personal Odyssey.

Leave a Reply