The Cuban struggle for independence and the remarkable Irishman who helped.

Johnny O’Brien was already famous among sailors for his extraordinary skill as a harbor pilot guiding ships through the treacherous waters of Hell Gate in New York harbor. But when he out-maneuvered Spanish gunboats and United States Revenue cutters to keep the Cuban rebels supplied with weapons and recruits in the 1890s, he became a legend. His waterfront cronies often accused him of not only starting the Spanish-American War but of keeping it going. The Cubans believed Johnny O’Brien was responsible for freeing them from four centuries of Spanish oppression and they gave him a lavish birthday banquet every year for the rest of his life.

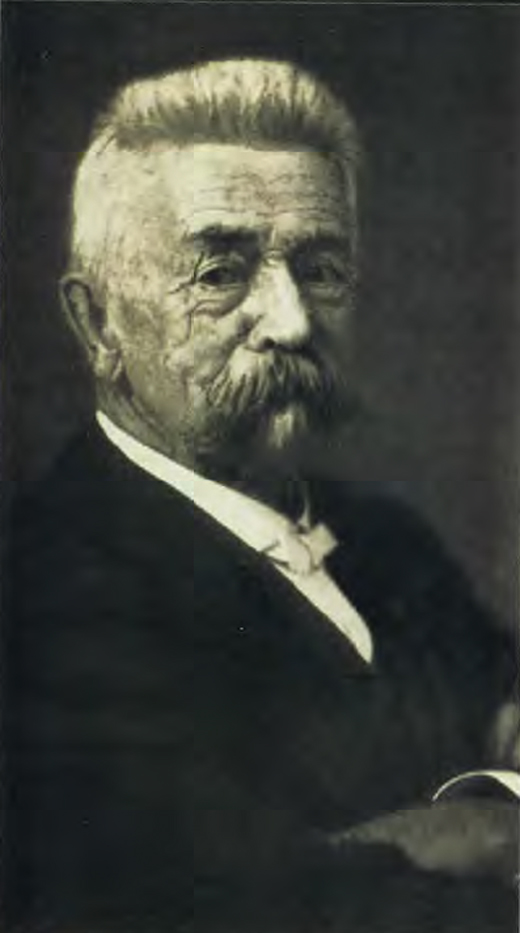

O’Brien was a short man with a thick gray handlebar mustache and the proud stance of a buccaneer. But there was no bravado about him, a New York Tribune reporter wrote. “He is one of the most daring and clear-headed that ever lived, a man with a hair-trigger intelligence that enabled him to act as swiftly as he could think.”

The Cuban struggle for liberty attracted O’Brien, who had known and admired Jose Marti, the rebel leader, and poet who operated from a New York waterfront office before he was killed in 1895. Marti’s successors raised money to buy arms and charter three powerful seagoing American tugs: The Dauntless, The Three Friends, and The Commodore, the first two most often piloted by O’Brien, who could navigate in pitch darkness to slip past blockades and war ships. He would run directly at a Spanish gunboat to force it to chase him out into the open sea and away from where he had just unloaded men and arms. He enraged the Spanish Captain-General Valeriano “The Butcher” Weyler, by landing cargo almost under his nose.

The public devoured newspaper stories of these daring “filibusters” by reporters like Richard Harding Davis and Stephen Crane. Crane, in fact, was on the Commodore when it sank off Florida and later wrote his famous story, “The Open Boat,” about his rescue. Despite sympathy for the Cuban cause, the United States government frowned on illegal gun running and chased after O’Brien who remained undaunted about breaking the law. “We were rebels once ourselves,” he said.

Johnny O’Brien was born on April 20, 1837, near the East River. His parents were farmers from County Longford, but in New York O’Brien’s father worked as a machinist at the East River shipyards.

“My childhood playground,” O’Brien often said, “was the neighboring shipyards,” where he learned to spin oakum and wedge treenails into boats. He learned to sail and navigate on his older brother Peter’s ferry — a large rowboat with a sail — crossing the East River to Brooklyn. Johnny was so intoxicated with the sea, his parents finally let him leave home at 13 to sign on as a cook on a fishing sloop. He eventually piloted fishing and sailing yachts, served as apprentice on the pilot boat Jane, and spent time on a Union ship during the Civil War.

“Being constitutionally disposed to giving orders rather than obeying them,” O’Brien took the required navigation training for a command rank as a pilot in the Hell Gate Pilots Association, forerunner of today’s Sandy Hook Pilots Association. He earned the name Daredevil Johnny because while he took chances, he always got through the then treacherous currents between the East River and Long Island Sound without mishap.

His name changed to Dynamite Johnny in 1888 when, at the age of 51, he carried 60 tons of dynamite to Panama in a seagoing yacht. An electric storm in the Gulf of Mexico sent current through the vessel that made O’Brien’s hair crackle like a hickory fire when he ran his hand through it. Despite the danger, he claimed that, “Being Irish I was favorably disposed toward dynamite on general principles.”

Despite his clandestine activities and long absences, O’Brien was a devoted family man married to a woman he described as “the best wife in the world,” who supported his activities. They lived with their eight children in a house in Arlington, New Jersey (now Kearney), that was watched constantly by detectives hired by the Spanish government. One night, O’Brien’s wife threw a pot of boiling water over one of the snoops who ventured onto the porch to eavesdrop under the window. His son Fisher suggested a way to beat the detectives at their own game. When O’Brien was followed from the house, Fisher would follow the detectives and once in Manhattan, find a way to let his father know where they were lurking. If O’Brien had no crucial meeting with the Cubans, he might confront the Pinkertons and buy them a drink.

When the USS Maine blew up in Havana Harbor killing 267 Americans, O’Brien was aboard Dauntless delivering a cargo of arms farther down the coast of Cuba. The sinking of the American battleship on February 15, 1898 was seen as an act of terrorism by the Spanish government and led to the Spanish-American War. Despite many investigations, the cause of the explosion was never determined. O’Brien, who knew a thing or two about dynamite, believed it was spontaneous combustion.

With “filibusterin’ in the dumps,” O’Brien held a variety of piloting jobs and one of these took him back to Havana in May 1902. He paid a visit to his old friend Tomas Estrada Palma, now president of Cuba, who asked O’Brien to be chief Havana Harbor pilot. There was one hitch. He would have to become a Cuban citizen. O’Brien refused to give up his American citizenship so the Cuban government waived the rule for him.

Years later the Maine was raised from the bottom of Havana Harbor to be towed out to sea. The United States Navy, apparently harboring no hard feelings about Dynamite Johnny’s past illegal activities, asked him to guide the Maine on her last voyage. So on the eve of St. Patrick’s Day, 1912, Dynamite Johnny O’Brien, now 75, put on his best morning suit, a starched white shirt and bow tie and climbed onto the rusted and patched deck of the battleship. He hung an American flag from a temporary mast. When the cortege of ships reached the three-mile limit, O’Brien’s crew came aboard the Maine and opened the valves in the bulkheads to let the water rush in, as sailors on nearby ships blew the mournful “Taps” into the air. Before he left, Captain O’Brien took the edge of the flag in his hand and kissed it.

“Old Glory vanished under the foam with a flash of red, white and blue as vivid as a flame,” he told a reporter. As the Maine slipped beneath the sea, the 30,000 people marching in the St. Patrick’s Day Parade in New York paused and all the church bells tolled for five minutes in a tribute to the heroes who had gone down with the ship.

O’Brien spent the last five years of his life in his home port. He died on June 22, 1917, and the Cuban government ordered a solid bronze casket and a huge floral wreath. Campbell’s Funeral Home on Broadway was crowded with his family and friends, Sandy Hook harbor pilots, Spanish-American War veterans, and Masons who led the service. Victor Hugo Barranco, an old friend who was with O’Brien just before he died, spoke on behalf of President Menocal of Cuba, about the man who had done so much toward freeing the island from the rule of Spain. And while no bells tolled throughout the city that day, and Dynamite Johnny was no longer front-page news, he received a respectful obituary in all the newspapers. ♦

_______________

Editor’s Note: Marian Betancourt is writing a book about Captain O’Brien and other people of New York Harbor. She asks that anyone with information about O’Brien and his descendants contact her at MarianBet@aol.com. At the time of his death, Johnny lived at 896 South 17th St., Newark, New Jersey.

My father was Salvador Acosta Casares O’Brian Zaldivar .

He has a great grandfather that left Kenmare to Boston with his sister.

He married a French lady and lived in Nuevitas, Camagüey, Cuba.

He was a merchant marine. His name was John O’Brian. He left in

1875. Any relation to Johnny Dynamite O’Brian?

Any information that you could give me will be greatly appreciated.

My grandfather was Edgar O’Brien, one of Johnny’s grand children. My sister and one of my mom’s cousin’s attended a wreath laying ceremony in Cuba last year at his memorial I just recently found a song on Youtube that was written by Cuban singer-songwriter Enriquito Núñez Díaz. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Gr7d-jrcPI) . I always wondered if he had children in Cuba. Johnny was from New Jersey originally. But he did work out of New York Harbor. There is a book you can see in .pdf online. file:///C:/Users/williacl/OneDrive%20-%20Nokia/Personal/A_captain_unafraid.pdf

I hope this helps some. Please let me know how it turns out.

Bill Clayton email: billclayto@gmail.com.

Hi! Dynamite Johnny O’Brien is my great, great, grandfather! I found this article about him and was excited.

I have not been in touch with anyone and have lost all contacts. I live in Colorado,

in the Rocky Mountains with my wife. My last contacts were in Washington state.

Dad (John O’Brien Sr.) went to be with the Lord around 1995-1996.

To be put in touch with any relatives, would be greatly appreciated!

Thank you.

Respectfully, John O’Brien Jr.

My grandfather left Seattle to alaska.1914.captain dynamite Johny O’Brien on the Victoria. I bought today the photo album of the maine.signed on christmas.johny O’Briens sister said it was a gift from Johny. Paid $75 . Wow so cool 😎