The search for the Japanese midget sub sunk off Pearl Harbor, Dec. 7, 1941, had been ongoing for 61 years until Terry Kerby came along. Pat Bigold talks to the man who made the most significant modern marine archaeological find ever in the Pacific, second only to the finding of the Titanic in the Atlantic.

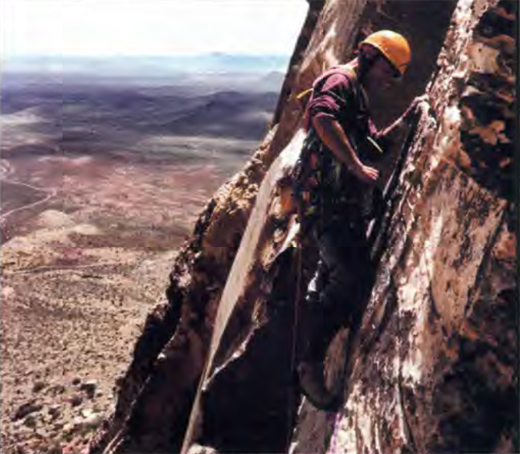

Honolulu, Hawaii: Terry Kerby loves to rock climb Nevada’s Whiskey Peak, hike the High Sierras, ride Hawaii’s big waves and roam Ireland when he has the chance. He’s the classic don’t-fence-me-in bachelor. But the gregarious blue-eyed, sandy-haired Irish-American’s sense of adventure is never bigger than when he’s confined in a 24-foot-long, 7-foot-diameter research submersible.

He spends up to 600 hours a year in them. The 53-year-old former college gymnast wriggles his 5-foot-11, 188-pound frame into a command sphere that shrinks to 5 feet in diameter with instrumentation and equipment.

Kerby usually has two passengers with him who must lie on their stomachs for the eight- to 10-hour duration of each dive. Kerby kneels with his head resting against a pad while he commands the submersible and peers out the middle view port. But even when he’s 6,500 feet down he never feels confined. “Every time I hear the hatch close I get a rush,” he said with a broad smile on Discoverers Day.

Kerby managed to rewrite the history of WWII in the Pacific last summer aboard the submersible Pisces IV.

At noon on August 28, 2002, in 1,200 feet of water, three miles outside the mouth of Pearl Harbor, Kerby and his team from the University of Hawaii’s Hawaii Underseas Research Lab (HURL) spotted the wreck of a Japanese midget submarine that had eluded searchers for 61 years.

No one, not even Robert Ballard, famed discoverer of the sunken Titanic, the German battleship Bismarck, the American carder Yorktown and John F. Kennedy’s PT-109, had been able to find it.

It was the sub the destroyer USS Ward claimed to have sunk 70 minutes before the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor began on December 7, 1941. The sub was in the U.S. defensive sea area and trying to sneak into Pearl Harbor behind the supply ship Antares when it was fired upon. Despite testimony from crewmen of the Ward, there never had been any hard evidence of the incident until Kerby’s discovery which proved that the battle of Pearl Harbor began much earlier than thought and that the U.S. fired the first shots.

He can recall the moment of discovery vividly.

“We were doing our life support procedure and all of a sudden Chris Kelley (biologist), riding in Pisces V, comes on the underwater telephone and says, `Terry, Terry, we found it! It’s the midget sub!'”

Kerby, who is HURL’s director of facilities and submersible operations, replied with remarkable calm, “Roger that.” He then turned Pisces IV around and saw Pisces V shining its 1,000-watt lights on the 78-foot-long prize.

“We tried to be very professional on the phone (all communication is taped) but there was a lot of hooting and hollering and screaming when we were off,” said Kerby.

It was not reasonable to expect Kerby to contain himself. He’d been looking for the midget sub since 1984. And there it sat on the ocean bottom amid a huge dumping field of WWII debris that included airplanes, tanks, landing craft, a warship and a barge.

The sub, which Kerby is certain still contains the remains of the two Japanese Imperial Navy crewmen, is almost intact. A large bullet hole through the conning tower is the only evidence of damage.

Kerby said the hole, created by one of the Ward’s deck guns, immediately proved to him that this was the real thing. The fact that both torpedoes, each containing 790 pounds of explosive potential, were still in their tubes further insured that the discovery was authentic.

Chris Kelley, who was the first to spot the sub, recalled how he’d become “fairly pessimistic” about the prospects of finding her. The crews were on the third and final dive of the three trial dives allowed before the start of the science dive season. Time was also running out as these dives were the only opportunities they had each year to search for the Japanese sub before their nationally-funded research mission took them out to sea.

“It looked like we had covered the whole area,” said Kelley. “One of the things we found was an 18-meter cement girder, and that was irritating.” But Kelley said Kerby insisted on yet another pass over the area where the submarine was believed to lie. His instinct told him the object of the hunt was very near, and he was right. It tamed out that the submersibles had actually made three earlier passes within 30 to 50 meters of the midget sub.

“Terry’s idea to give it another try was what did it,” said Kelley. “He’s the one to get all of the credit for this. He pushed for it all the way.”

Kerby said that if the U.S. and Japan come to an agreement on what should be done with the sub, it could easily be raised from the bottom. “The bow and stern sections are completely up and off the bottom,” he said. “The currents have scoured the area out.”

After his discovery of the submarine, a reporter asked Kerby if he now considered himself in the same league with Ballard. It was an ironic question because Ballard had tried and failed to find the relic during a highly publicized 10-day National Geographic-sponsored expedition in November 2000. Ballard concluded that the midget sub must have escaped the Ward‘s attack and limped somewhere out to sea.

Kerby recalled that at the time National Geographic were “very concerned” that HURL’s submersibles might ruin the high-cost Ballard expedition by making the first sighting of the midget sub.

Kerby has piloted research dives in various areas of the Pacific for 24 years. His knowledge of submersibles, with which he admits a fascination since age 10, goes beyond the operational aspects. He personally shopped the world to find and purchase Pisces V and Pisces IV for HURL. Then he completely rebuilt both of the used crafts to replace the two-man submersible with a depth of only 1,200 feet that HURL had been using.

The Pisces three-man submersibles are capable of 6,500-foot dives. Each cost $4 million to make but Kerby was able to buy Pisces IV for $800,000 and Pisces V for $500,000.

“He knows them bolt by bolt,” said Kelley. “And he’s the one who’s been a tireless advocate of the submersible program all these years.”

Like the Renaissance man he is, Kerby not only keeps a scrap-book of stunning underwater photos but he also has his own hand-drawn images of the sights he’s witnessed and of the vehicles he’s ridden to the bottom of the sea.

His art is detailed, dramatic and so captivating that the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (umbrella agency for HURL) has some of Kerby’s work on display in its offices.

The most dangerous dives he remembers were made in 1987 into the active undersea volcano Loihi, located about 20 miles off the coast of the Big Island. “It was exciting but absolutely nerve-wracking,” he recalls.

Exploring pumps Kerby’s adrenaline and he’s not easily intimidated. On one Loihi dive he reached the bottom of a crater and probed the wall until the ominous sound of a landslide made him decide to surface.

“Sometimes if you’re exploring it’s hard to stop,” he says. “Seeing what’s around the next corner is what drives you.”

The California-born Kerby, who won the Coast Guard Commendation Medal for a 1973 rescue off Puerto Rico, is also a sought-after movie stunt man.

He’s worked on films such as the James Bond thriller For Your Eyes Only (1981) and the James Cameron sci-fi flick The Abyss (1989).

In one of the most nail-biting underwater sequences ever filmed, it was Kerby who carded a “drowned” Mary Elizabeth Mastrontonio under water from a sunken submarine to an underwater oil rig in The Abyss.

On the Bond film, shot in the Bahamas, Kerby worked as stunt man, dive-master, director of construction for a Greek temple 60 feet under water, pilot of a submarine for cameramen, and handler of tiger sharks used in key scenes.

It’s all in a day’s work for Kerby, whose family came to the U.S. from Ireland in the early 1800s. “There were three brothers that had left Ireland and the youngest was kidnapped on the London Bridge by a press gang and was never heard from again,” he recalls.

“The other two made it to America, and one wound up fighting for the North and the other for the South in the Civil War. The name might have been spelled Kirby back then.”

Kerby, who can do a believable brogue, said his heart is in Ireland though he hasn’t been able to travel there in years. “I used to visit a family in Wicklow during the 1980s who had a house that went down to the sea,” he remembers. Until he finds the time for another trip, he’s content to settle for a pint in one of Honolulu’s five Irish pubs if he needs a quick Celtic fix.

What he loved most about Ireland, he said, was driving “on the wrong side of the road,” checking out castles and eating in the pubs. “There’s nothing better than smoked salmon, crisps and a Guinness,” he said. “And I love the smell of burning turf.” ♦

_______________

For more information on the midget sub discovery, check out: http://imina.soest.hawaii.edu/HURL/midget

Leave a Reply