Niall O’Dowd interviews Chris Matthews of CNBC’s Hardball, one of prime time’s most popular programs.

℘℘℘

If Chris Matthews were a cat, curiosity would have killed him long ago. In our 90-minute interview in a Washington restaurant he asked as many questions as he fielded and he ranged over practically every major world problem, offering opinions, facts and speculations on all.

Matthews, 56, is intensely curious. When the interview begins we discuss Michael Collins, the crisis in the North, the economy of the Irish Republic, Ulster Unionist leader David Trimble, Gerry Adams and why and how former President Bill Clinton got involved in the Irish peace process. And that’s just in the first 10 minutes.

Most of the questions come from him to me. I try in vain to put him in the spotlight but he is a natural inquisitor. My sentences are interrupted in mid-stream by a single “Why?” barked in the TV style that has made him famous. Even the waiter gets interrogated at length about the specials.

Matthews has entered the restaurant with his tie askew. The maitre d’ gently puts it in place while Matthews divulges the history of the tie and why he wore it that day. He has the opposite of attention deficit disorder. Even his tie interests him.

When he takes a question, the answer flows like a stream of consciousness. His television persona is no act. When the klieg lights come on, he has said, “The Chris Matthews you see and hear is the only Chris Matthews there is.” And it is true.

It is the persona he has become famous for. He is one of the most recognizable faces on television as the host of MSNBC and CNBC’s Hardball, a no-holds-barred politics and current affairs program, five nights a week.

The show often has an uneven quality. Matthews suffers poor guests badly, constantly interrupting while trying to make them speak sense. The result can sometimes sound like one long monologue.

His pet hate, he says, is politicians who come along with talking points all nearly typed out. He can be merciless, teasing them for their lack of confidence in their own abilities, cutting them off in mid-sentence. He shows no reverence or respect, no matter how high and mighty the guest assumes himself to be.

But when the topic and the guest are interesting, Hardball is one of the best watches on television. It lacks the pomposity and solemnity of many of the political talk shows where you can almost feel the interviewers puffing themselves up to ask an “extremely important question.” Matthews freewheels, though he sometimes tries to do it uphill. You can see how he wins most of his debates just by exhausting his guests.

He has two innate abilities though, the first to cut through the bullshit, the second to ask the question that the ordinary Joe or Jane sitting at home would love to ask. The rowdy atmosphere and constant interruptions give the show a saloon-like quality with Matthews as the bartender, and the cut and thrust can sometimes enliven even the most boring topic.

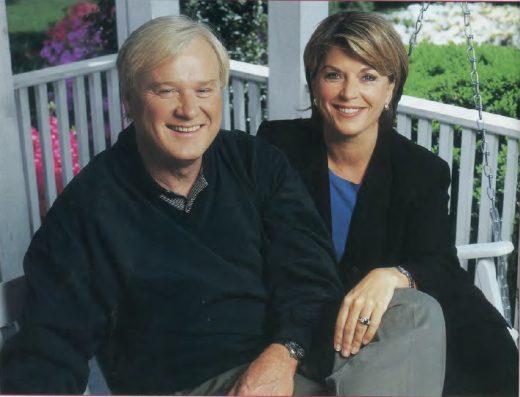

The format is no artifice, however. Matthews does not wipe off the greasepaint and return to his normal self after the show. He is exactly as he appears and the show fits him like a glove. His wife Kathy must find him exhausting.

George Will once noted that Matthews is “half Huck Finn and half Machiavelli” and “an exuberant guide to the great game of politics.” The buttoned-down Will, with the prim bow-ties, doesn’t use words like “exuberant” too often, one suspects.

From his earliest memories Matthews wanted to work around politics. Growing up in an Irish neighborhood in Philadelphia and later in a rural setting near Bucks County, Pennsylvania, he immersed himself in the science.

He remembers in 1952, at all of six years of age, professing fealty to Dwight Eisenhower, the dashing general and hero of World War II, who was elected president that year. His father, Herb, a court reporter in Philadelphia, approved. Herb was a Protestant who later converted to Catholicism. All his life he loved the Republican Party and voted for Nixon over Kennedy. (At age 82, he has recently married again).

Herb’s mother was a Protestant immigrant from Northern Ireland who came over to a life in domestic service in the United States. After her English-born husband died she eventually built a one-person laundry service which helped her family through hard times. “She spoke with an Irish accent and conveyed a strong, upbeat fun-loving attitude her whole life,” says Chris.

The most influential person for Matthews, however, was his maternal grandfather, Charlie Shields, a Democratic committeeman for his neighborhood in North Philadelphia. At night, after supper, he took his grandchildren on long walks through the streets of his domain, filling their heads full of political lore and wisdom. Young Christopher John Matthews was enthralled.

His mother, Mary Teresa Shields, grew up in North Philadelphia and scandalized the locals with her marriage to a Protestant. She moved her family from their protective cocoon of an Irish neighborhood to an area of converted farmland in rural Pennsylvania. Like her husband, she too in time became a rock-ribbed Republican, a tradition that ran deep in the family. Matthews’ brother Jim is now a Republican commissioner in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania.

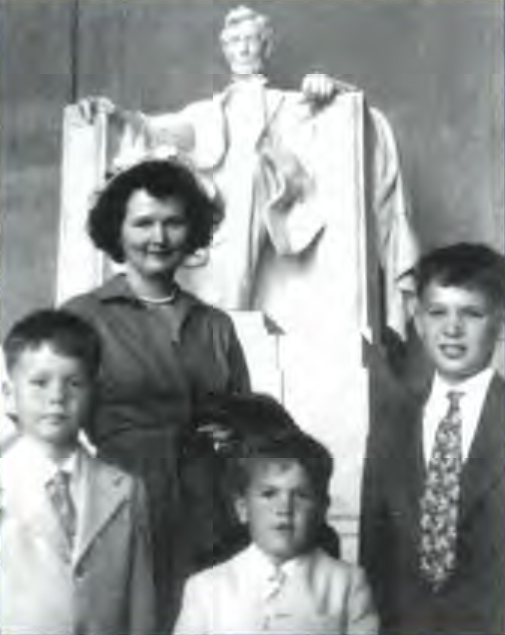

One event in his early life stands out for Matthews. In 1954 his parents took their three oldest sons to Washington to see the Capital for the first time. Matthews says the “trip was unforgettable” and even back then he was hooked.

By 1960, as a teenager, he cried when Kennedy beat Nixon in the race for the White House. His family, he says, were “cloth-cap Republicans” and he found himself siding with his father and his long-held views. His mother, he knew, was more conflicted, her Catholicism and Republican leanings at odds with each other.

To this day he retains a fascination for Nixon. “I have some pull towards Nixon,” he says. “He had a hard life, and he had no social confidence, but he had a will to win, that’s why he got into politics. He got his original chance by a fluke but he made the best of it.”

Matthews’ childhood fascination with that election led him to write Kennedy and Nixon (1996), a very well-received book which the Washington Post tagged as “a beautifully written, persuasive narrative.”

On November 22, 1963, Matthews was a freshman at Holy Cross in Massachusetts when word came through that Kennedy had been assassinated. “I don’t think I have ever felt as deadened by any event as the assassination of Jack Kennedy,” he says. He was still a Republican and a Barry Goldwater fan, but he realized the country had crossed a dark threshold.

Just ahead lay the Vietnam War, which Matthews soon opposed because right from the beginning, he felt it was not winnable. Gradually, he found his political perspective changing. The youth of America were looking for a leader who showed that he cared about what they were thinking.

Matthews and millions of others found that person in Minnesota Senator Eugene McCarthy, who took on Johnson in the 1968 Democratic primary and hastened the end of the war and the president’s career. “He was the kind of Democrat I could see myself becoming,” says Matthews.

When Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King were shot Matthews found himself even more disenchanted. He had a student deferment from the draft but it was about to elapse. General William Westmoreland was asking for 250,000 more troops after the Tet Offensive sent shockwaves through South Vietnam. Matthews was on the firing line.

He sidestepped by joining the Peace Corps and went to Swaziland in southern Africa. He spent two years there helping the locals to organize their small businesses better. By 1970 he was back in the U.S.

Speaking of that period, he believes there are still lessons for Americans from the war. “Vietnam remains a chronic reminder that even the most powerful nation in the world cannot work its will everywhere,” he says.

Back in the U.S. Matthews wanted to fulfill his life’s ambition by working on Capitol Hill. Wayne Owens, a top aide to Senator Frank Moss of Utah and a former Peace Corps volunteer, hired him both as an aide and a Capitol policeman. Daytime he worked in the senator’s office, then at 3 p.m. he donned his police uniform and his .38 caliber weapon and took up his guard duties.

In 1974, urged on by his boss, Matthews decided to run for office himself in his native Philadelphia against a strong incumbent, Representative Josh Eilberg. He had no money, no real political contacts and few prospects. He says it was “the toughest thing he ever did.” He was soundly defeated but came back to the Hill to some newfound respect.

He began working for Senator Edward Muskie of Maine, then a contender for the presidency. From Muskie he said he learned “how to get things done in Washington.”

In 1977 he began work at the Carter White House as a presidential speechwriter, the job he says was the most fun he had before Hardball. When Carter was defeated he went to work for House Speaker Thomas “Tip” O’Neill, the only Democratic leader to survive the Reagan landslide in 1980. He was named administrative assistant, the top staff position on Capitol Hill. It was a long way from his part-time-policeman days.

He describes O’Neill as a man with “a mountain of courage, history and good-will.” Many expected O’Neill would be road kill in Reagan’s drive to put through his conservative agenda. Instead he stood up to Reagan and, Matthews says, saved many social programs that would otherwise have been cut.

Following the O’Neill stint, Matthews began to focus on journalism. By 1992 he was writing a syndicated column for the San Francisco Examiner, as their Washington Bureau Chief and was also working for ABC’s Good Morning America for whom he covered the South African elections in 1994, witnessing the end of an era of white supremacy. By 1998, Matthews was invited by CNBC and MSNBC to host a political show. He decided on the title Hardball named after a book he had written.

Asking Chris Matthews for an opinion is a little like fishing in a bowl of goldfish. You are guaranteed a successful outcome.

On the possible war in Iraq he is vocal. “I can’t figure out a strategic threat from Iraq,” he says. “Why should we risk it? We are basically acting like world protectors from Palestine to Cuba — where’s our sense of humility?”

He believes that George W. Bush lacks a sense of history on the Middle East. “It’s like a Brazilian beat, there are two sounds going at the same time. An American president needs to be pro Israel, but we also need to be honest brokers and we need to keep both in our head at the same time. Bush is only pro Israel,” he says.

Matthews is damning about the “neoconservatives” that, he says, surround the president and have a skewed view of American foreign policy. “They think they can pretty much do as they wish anywhere in the world and diplomacy is a poor second to military force.”

He believes General Colin Powell is the counterweight, but his influence has waned. The current Israeli occupation will end badly, he says. “It will only radicalize the people in the occupied territories. There has to be a peace plan.”

After lauding George Bush to the skies on the fight against terrorism, Matthews’ enthusiasm has waned — much of it because of the people Bush has surrounded himself with. But he hasn’t given up on the President yet.

He says he’d love Bush to pick a heavy-weight to stand up to the conservatives as his running mate in 2004. “I like Rudy [Giuliani],” he says. “He’s a tough bastard, exactly what is needed.”

On the Democratic side, of the current contenders Matthews likes Massachusetts Senator John Kerry who has a stellar Vietnam War record and a reputation as a maverick on some issues.

It is clear though that he is also a great admirer of Senator John McCain, the Arizona Republican who has a reputation for speaking his mind. He feels McCain embodies the best of the American spirit. Matthews’ next book, America, Beyond Our Greatest Notions, hails the reluctant-warrior theme in American life, the Cincinattus who returns to his plough and his fields after being forced to fight.

“Pioneer spirit, optimism, always rebellious about government, pain in the butt, take on the establishment, the frontier spirit” is how he characterizes his heroes.

Matthews recently had a reconciliation with former President Bill Clinton while both were in Dublin for an awards ceremony. They stayed out late on a pub-crawl, says Matthews. He was bitterly critical of Clinton during the Lewinsky affair. “I just don’t understand how a man who could get the hard part of his job couldn’t get the easy part,” he says.

He has enormous respect for the former president’s political and social skills, however. “If he landed on a foreign planet and met aliens, he’d figure out faster than anyone what they did, what constitutes sex up there and he would have them laughing at his stuff in no time.” he says laughing.

He thinks Hillary Clinton will definitely run for the White House but says her liberal views mark her as outside the centrism which he believes is the centrifugal force in American life.

Matthews was honored by the Ancient Order of Hibernians recently and on March 16 he was the keynote speaker at the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick Dinner in New York. He was guest of honor at The American Ireland Fund’s August bash on Nantucket Island.

On several of his Irish speaking engagements Matthews has discussed September 11 and the incredible Irish subtext to that tragedy. Midway through his talk, he says, he begins reading the names of police and firefighters who died, the majority of them Irish. He says you can hear a pin drop.

For the only time in the interview his eyes well up and his voice cracks. “Now, those men and women are real heroes,” he says softly, for once lost for words. ♦

Leave a Reply