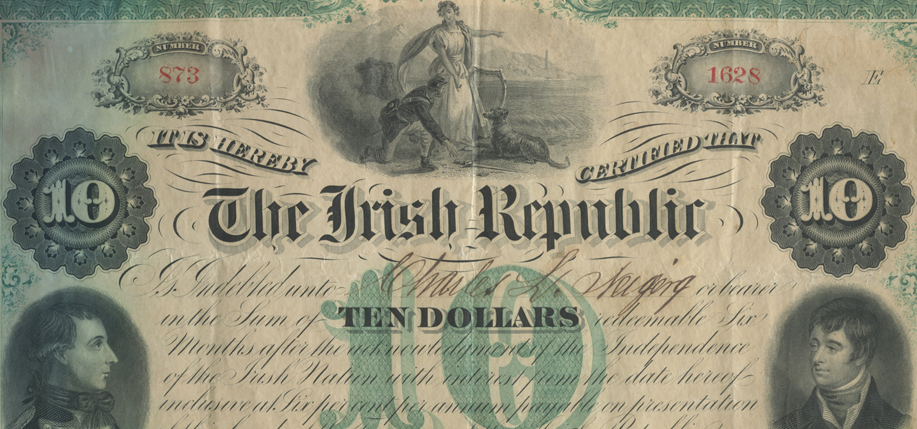

The Fenians sold these bonds in the name of the then non-existent “Irish Republic,” to help finance the Canadian invasion. The vignette depicts Cathleen Ní Houlihann gesturing with one hand to an Irish-American Civil War veteran to pick up the sword again to go and fight for Ireland which she points to across the sea. With 6% compounded annual interest from its date of issuance in 1866, this bond would be worth about $30,000 if the current Irish Republic would agree to redeem it. The above $10 bond is courtesy: Patrick Doherty Collection.

℘℘℘

Dusty, dirty and tired, Michael O’Doherty rode on horse-back into Westport, Missouri, in August of 1861, just behind a stampede of news and rumors about Stonewall Jackson’s surprising first defeat of Union troops at Bull Run. Freshly discharged from Indian containment duties in New Mexico, the veteran cavalryman, a native of Killarney, Co. Kerry, found himself the center of attention in the teeming outfitting post near the heads of the great Oregon and Santa Fe trails.

Military conscription efforts were at a fever pitch, and men of military stature and experience were being hotly recruited for local volunteer units, both Union and Confederate. O’Doherty, in his memoirs, scoffed at the competition for his professional services:

“They were raising troops for the south. Our names were registered in the hotel book and they knew we were the very thing they wanted, well drilled cavalry men, intelligent and sober. Myself being registered with my full rank of quartermaster sergeant, they were not slow to offer me the rank of captain and the other boys commissions. I respectfully declined by telling them that there was no particular mark of distinction in the rank of captain in volunteers and if there was I could not accept it as I had sworn allegiance to the stars and stripes and no consideration could make me betray my obligation as an Irishman and a federal soldier.”

The Irish, as a rule, were quick to volunteer for military service in the Civil War. Some joined to prove their patriotism; some joined for the chance to get a lick in against Great Britain, which supported so much Southern industry. Recruitment posters for Irish regiments declared, “cotton lords and traitor allies of England must be put down.”

During the course of the war, as many as 150,000 Union soldiers were Irish-born. More than 35 Union regiments were officially designated “Irish.” Conversely, an estimated 40,000 Irish-born fought for the South. In addition, thousands of first-generation Irish fought on both sides of the conflict.

Michael O’Doherty, however, was content to raise a family and ply his trade as a bootmaker, and spurned overtures from Irish Company B of the United States Volunteer Reserve Corps.

“I retired,” he wrote, “for I was disgusted with the kind of soldiering then going on — green citizens that never mounted a war horse or never drew blade from a scabbard…capts., majors, cols. and genls, because they were rich or could wield political influence.”

It was only when the war ended in 1865 that Michael O’Doherty regained his taste for battle. Fueled by the agitating rhetoric of a growing American Fenian movement, thousands of Indian and Civil War veterans put their uniforms back on and began training again. Their goal was to attack and capture thinly guarded, English-controlled Canada, and hold it hostage in return for self-rule in Ireland.

O’Doherty explains, “The reader may ask what was the object of attacking England in Canada, and not on Irish soil. The reasons were obvious. First we could not infringe on the international law without being interfered with by the United States. Although we did. We thought by making a terrible dash on Canada, conquer it from England, for the time being be recognized by the United States as beligerants, fit out a navy to make war on English commerce and throw men and munitions of war to Ireland and inaugurate a successful revolution for an Irish republic on Irish soil and then leave Canada to the Canadians, that was [our] object, and the principal one.”

Irish military men, mostly former Union Army officers, captured the imagination — and wallets — of Irish Americans, with grand visions of 200,000 battle-hardened Civil War vets marching on Canada. Chapters of the new Fenian Brotherhood sprouted in virtually every American city with a significant Irish population. Condemned by the Catholic Church for its tendency toward anarchy and bloodshed, the movement boasted 50,000 members nationwide.

In 1865, O’Doherty wrote, “[Our] circle worked hard. We subscribed the very little money we wanted for our families to the general funds. We bought Fenian bonds that wasn’t worth the paper they were printed on. Those bonds were got up in this way so many years after the establishment of a Republican government on the soil of Ireland the Irish Republic promises to pay the bearer in gold at so much percent premium [on] the amount of [the] note. These bonds were furnished to agents, supposed to be good patriotic Irishmen, for sale and they were bought up by poor hardworking men and women all over the country. Bought one myself for the last few dollars I had to spare and so did others in Kansas City.”

O’Doherty was chosen as Kansas City’s delegate to the Fenian Convention in Troy, New York, in September 1866, where he gave a rousing speech, pledging the support of his fellow Irish from the Midwest.

“We rallied in Kansas City and raised some money but before we had time to say ‘Jack Roerson’ the fuss was all over,” O’Doherty recorded. Without sanction of the Brotherhood, O’Neill led a small, ill-equipped band of America’s most radical, hard-core Irish fighting men back into Canada, where they engaged a waiting force of English-Canadian troops. The fight was over in a matter of hours.

“There was a skirmish but let me draw a curtain over the scene — it was not worthy of record,” wrote the disgusted Doherty. He and others like him put their guns back in the closet and resigned themselves to earning a meager living and raising families. “Business was very dull, and the country was after going through the trying ordeal of a terrible sickly season,” he wrote in one of the last notations in his memoirs. “I was well broke down in pocket. After sacrificing family affairs, time and neglect of my little business, all for Ireland and, to be candid, for a little historical fame among my countrymen…I was now as poor as Job’s turkey.”

O’Doherty lived out his life in a little frame house that he built on a hill overlooking the wide and slow-moving Missouri River. “By good look [luck] I had invested some money in a little real estate before the Fenian excitement,” he concluded, “else it would all be gone.” ♦

Leave a Reply