The haunting Irish Hunger Memorial, unveiled on July 16 in downtown Manhattan, offers visitors a stunning view of the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island. This is fitting, given that these landmarks have greeted generations of Irish immigrants to New York City.

Sadly, however, as visitors will learn, your eyes cannot avoid another site — Ground Zero, just footsteps from the memorial’s Battery Park City location at Vesey Street and North End Avenue, on the banks of the Hudson River.

Back when ground was broken for the $5 million, 1/2 acre memorial on St. Patrick’s Day, 2001, the ceremonies were held in the shadow of the Twin Towers. The memorial was slated to open on St. Patrick’s Day 2002. Of course, September 11 intruded.

So, when Irish President Mary McAleese, Governor George Pataki and other dignitaries gathered, just one block from Ground Zero, to unveil the memorial to a Hunger which killed over 1 million Irish, 9/11 references were inevitable.

Rudy Giuliani made a point of saying that Irish Americans sacrificed more than any other group on September 11.

“One hundred and fifty years [after the Famine], the spirit of the Irish people was the backbone which America relied upon during the worst attack in our nation’s history,” said the former mayor, who received loud applause.

During an earlier tour given to Irish America, Dr. Maureen Murphy, the project’s historian, said it was inevitable that visitors would think about both tragedies.

“You can come down here and reflect on the Famine. You can come down here and reflect on September 11,” said Dr. Murphy, whose knees and work gloves were stained brown with soil from which dozens of plant species native to Ireland now grow.

Visitors can now stroll onto the Hunger Memorial at street level, before slowly winding up a dirt path which ultimately rises nearly 30 feet. The site was patterned after ruins — as well as information gathered by folklorists in County Mayo. But Adrian Flannelly, the Irish radio personality who is the project’s cultural liaison, says: “Really, this could be [a ruin] anywhere in rural Ireland.”

Flannelly has a more-than-professional attachment to New York’s Hunger Memorial: His father, Patrick, was one of the educators who helped gather information about living conditions in the Mayo village of Attymass after the Famine.

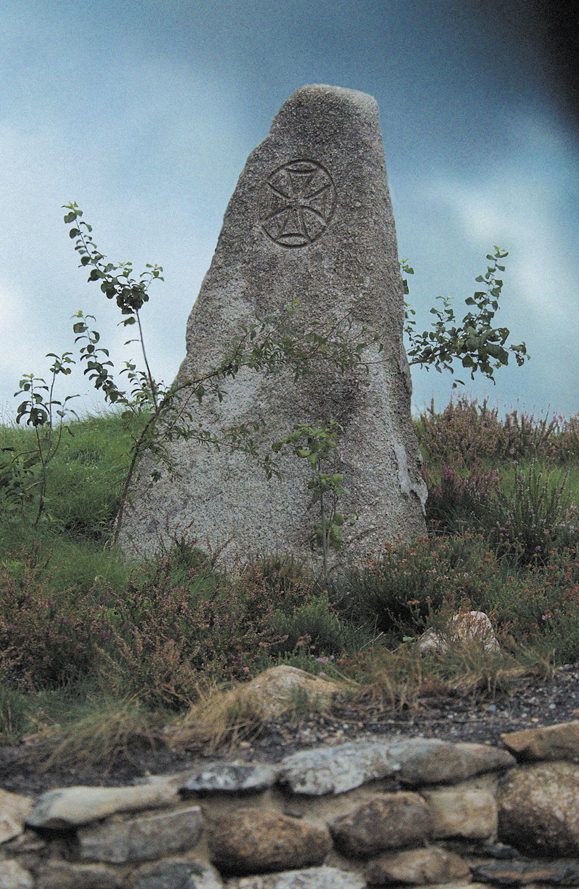

Central to the memorial is an 1830’s stone cottage from the village of Carradoogan, which was donated by the Stack family.

But for all its 19th century trappings, the Irish Hunger Memorial is very much a 21st century historical exhibit.

According to Brian Tolle, the artist who won the fierce competition to design the memorial, it is important that visitors learn not just about the Irish Famine, but hunger in the contemporary world.

“It’s a living alert, a center for hunger around the world,” says Tolle, whose design was inspired by a trip to County Mayo following his selection. “What happened in Ireland in the 1840s should never be repeated anywhere in the world.”

Visitors can take the path that winds upward to what seems like a cliff edge overlooking the Hudson River and descend down into the abandoned two-room cottage. As you stroll around the exhibit, you will be able to read passages from history books and Famineera political debates on the structure’s wall. You will hear songs about immigration and even hear about contemporary famine, thanks to the memorial’s audio component.

Meanwhile, the memorial is handicapaccessible, which allowed Tolle and his team to create an impressive entrance hall into the cottage, which contains additional writing and audio.

The Irish Hunger Memorial will be updated on a regular basis with news about contemporary world hunger. Indeed, a Mass before the dedication ceremony celebrated by Fr. Jack Finucane, one of the founders of Concern Worldwide, the Irish relief organization, served as a powerful reminder that thousands of children die every day from starvation.

Of course, there have been raging debates about the extent to which the British were to blame for the Great Hunger. Tolle hopes to address this problem by offering a diversity of information at the Hunger Memorial. And a library/exhibition space is planned for a space close to the site. “We’ll put it all out there and let the visitor decide,” said Tolle.

What is not up for debate is the huge amount of material from Ireland which went into this memorial. Though most of the stones are from Mayo, all 32 Irish counties are represented by rocks on the site. Many of the plants, meanwhile, are not only native to Irish soil, but were actually grown from Irish seeds. Kilkenny stones have been used for the walkway, while limestone from Clare was used to build the walls.

When the memorial was finally unveiled, visitors on that sun-splashed July day gave it unanimous applause.

Battery Park City resident Ed Ryan, whose Mom came to New York from Galway, has actually watched the memorial take shape from day one.

Still, nothing could quite prepare Ryan, 63, for seeing the memorial for the first time.

“I think it’s wonderful,” said Ryan, leaning on a walker, his blue eyes surveying the greenery. “My father’s people came over during the Famine,” Ryan said. “They didn’t talk about it much.”

Ryan — as well as President McAleese and Governor Pataki — said the memorial will help people come to terms with the starvation that eventually sent millions of Irish emigrants to North America.

Many visitors appreciated that the Irish memorial also sheds light on contemporary hunger.

Margaret DelBango (nee Walsh), a Ladies AOHer from Staten Island, said: “This memorial is a long time coming. It’s a great reminder of the suffering that was caused. It is also a reminder that we should be magnanimous in our wealth.”

Along with Pataki, Giuliani and McAleese, New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg was on hand, as were New York Archbishop Edward Cardinal Egan and international rock star Bob Geldof. President George W. Bush sent written greetings to a crowd that represented a who’s who of New York Irish, ranging from writers Pete Hamill and Frank McCourt to police officer Steven McDonald who was injured in the line of duty and is now confined to a wheelchair.

Irish musicians, including Paddy Reilly, who sang “The Fields of Athenry,” a song about the Irish Famine, performed for the crowd who had came to see the long-awaited, multi-media structure.

Irish immigrants Aileen and Tom Hilliard were not disappointed.

“I think it’s beautiful,” said Aileen, who emigrated from Cork in 1964, and now lives in Stony Point, New York. “It will always keep you in touch with what happened during the Famine. And how the Irish survived.”

“It’s an education for me,” added Tom, originally from Longford. “This is really what it might have looked like during the Famine.”

Indeed, visitor after visitor, speaker after speaker seemed stunned at the detail and beauty of the memorial.

“It’s nice to see the Irish getting a little recognition for what they went through,” said Peter Brady, a FDNY Lieutenant with Engine 155, and a Emerald Society member for 23 years.

Twenty-two-year-old Belfast student Cailin Hardy, in New York as part of a cultural exchange program, was struck by the Irish pride on display at the ceremony.

“At home you almost feel afraid to be Irish…here you’re almost afraid not to be,” said Hardy with a laugh.

Indeed, perhaps it was Malachy McCourt who put it most poignantly — and humorously. Surveying the hundreds of Irish Americans in the crowd, he said: “This only proves that death, to the Irish, is not always fatal.” ♦

Just visited this important memorial.

My only wish is that you could provide the writing on the walls in a pdf format. I found it difficult and fragmented to read while walking.

Thank you.