“This is the first time the inside story of the Irish peace process has been told by so many of the major politicians and paramilitary leaders who helped shape it.”

– WGBH executive producer Zvi Dor-Ner

℘℘℘

Endgame in Ireland, a four-hour PBS special documenting the hard-fought road to peace in Northern Ireland from the onset of The Troubles in the late 1960s to the IRA decommissioning of arms in October 2001, premiered on PBS in July. Interspersed with interviews with leading decision-makers from Ireland, North and South, the United Kingdom and the United States, Endgame presents vivid historical footage of The Troubles and the political attempts to solve the seemingly unsolvable – including the negotiations which paved the way for the 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement and the 1993 Downing Street Declaration, the secret contacts between John Major and the IRA as well as the events which nearly scuppered the process – the British failure to act on the IRA ceasefire, Unionist intransigence, and the breaking of the IRA ceasefire and subsequent bombings at Canary Wharf and Manchester. The footage is accompanied by a spare narrative that never attempts to put its own voice on proceedings but merely provides chronology and context for the video footage and a link from one interview to the next.

Among the interviewees featured are Irish prime ministers Garret Fitzgerald, Albert Reynolds, John Bruton and Bertie Ahem; the former UK Secretary of State for Northern Ireland Mo Mowlam; British Prime Ministers Margaret Thatcher, John Major and Tony Blair; Northern Ireland’s first minister David Trimble; the SDLP’s leader and deputy leader John Hume and Seamus Mallon; the Reverend Ian Paisley, MP; Sinn Féin’s president Gerry Adams and Minister of Education Martin McGuinness. On the American end, former U.S. President Bill Clinton, George Mitchell, Edward Kennedy, Bruce Morrison, Irish America/Irish Voice publisher Niall O’Dowd and various others who helped the process along, are shown. Behind-the-scenes negotiators such as “the link” who met with republican paramilitaries on behalf of the British Government, and Fr. Alec Reid whose secret role arranging for the SDLP and Sinn Féin to meet, are also included in this compelling analysis of the political process that led to peace.

And indeed, it is the personal accounts which make the series so compelling. Instead of rhetoric by the politicians and paramilitaries, sufficient time has passed and the road towards peace has hopefully been so far traveled that overriding honesty and sometimes even soul-baring on the parts of those interviewed is no longer political suicide.

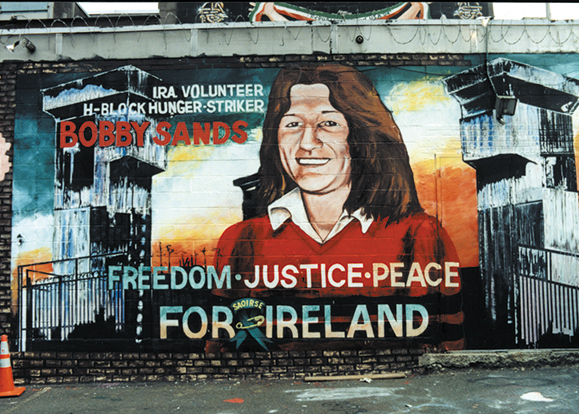

The series shows how incidents and events which in themselves might have appeared isolated and even futile, opened the road to Endgame. The 1981 Hunger Strike, which left Margaret Thatcher famously unmoved and which resulted in the deaths of 10 republican prisoners, might at the time have seemed a failure for the republican cause, yet it paved the way for future peace by generating worldwide sympathy and helping to unify and strengthen Sinn Féin. Over time, one sees the politicization of both republicans and loyalists as they gradually turn “from the bomb to the ballot box.”

The detachment of loyalist Michael Stone as he describes his attempts to assassinate Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness at the funerals of Mairead Farrell, Sean Savage and Danny McCann (three republicans killed by British Special Forces in Gibraltar) and instead ends up killing three mourners and injuring 60, might be chilling but it gives a unique insight into the mind of the loyalist paramilitaries.

Nobody who has followed Northern Irish politics can ever have been in any doubt as to the fervor of Unionist politicians, who, particularly in the ’70s and ’80s, won the media war over their nationalist counterparts (helped no doubt by the fact that due to a broadcasting ban, Sinn Féin were banned from the airways in Ireland, and in Britain their voices were dubbed). However, in the propaganda war between the paramilitary organizations, it is acknowledged even by the loyalists that the republicans won hands down. After the first IRA ceasefire David Ervine says that loyalist paramilitaries felt excluded from the political process to the extent that they asked the Archbishop of Canterbury, George Carey, to intervene with John Major to find out what deal had been done with Sinn Féin to bring about the ceasefire.

On the subject of Thatcher, it is interesting to see recollections from former advisers David Goodall, deputy secretary at the Cabinet Office, and Charles Powell, private secretary to the prime minister, portraying Thatcher as someone who didn’t understand the intricacies of the Northern Irish situation. According to Goodall, Thatcher’s “way of teasing out a problem was to sort of throw out various outrageous suggestions — she said, `Um, you know the Irish are quite used to movements of population. If the Northern population want to be in the South, well, why don’t they you know move over there, after all, there was a big movement of population in Ireland, wasn’t there?'” [Thatcher is referring to Cromwell’s “To Hell or Connaught” policy]. Powell, meantime, appeared to gently deride Thatcher for wanting to redraw the border between the North and South into a straight line to make it easier to defend. “She said, `Couldn’t we redraw the border to at least make it more defensible?’ She thought that if we had a straight line border, not one with all those kinks and wiggles in it, it would be easier to defend.” Notwithstanding Thatcher’s contribution to the signing of the Anglo-Irish Agreement, it is little wonder peace didn’t come about while she was in office.

The program is even-handed both in its treatment of the issues and the two communities and in its selection of interviews and footage. In the assiduously balanced selection of sectarian atrocities, the program makers ensure that neither side of the sectarian divide can feel discriminated against, and while events that gave rise to The Troubles, including civil rights abuses and Bloody Sunday, are briefly documented to provide context, it is the actual process that leads to peace on which the focus is placed.

The Irish-American involvement in the road to peace is given good coverage with the U.S. entry visa that Irish prime minister Albert Reynolds persuaded Bill Clinton to grant to Gerry Adams being seen as a crucial development without which there might have been stalemate. Bill Clinton’s envoy, George Mitchell’s negotiating and chairing skills in the all-party negotiations were obviously of incalculable benefit. His lack of a personal agenda in the outcome of the talks meant that he was able to win the trust of both sides and keep the dialogue moving. Although even his enormous reserves of patience were tested by the slow progress, to the extent that he had to set a deadline of Easter 1998 to help expedite matters which eventually led to the Good Friday Agreement.

In the final analysis, Endgame shows how much the peace process was driven by Sinn Féin. And in light of recent escalation in loyalist violence towards Catholics, and Unionist determination to oust Sinn Féin from the Assembly, it offers a stark reminder of what the consequences could be if the peace doesn’t hold. ♦

Leave a Reply