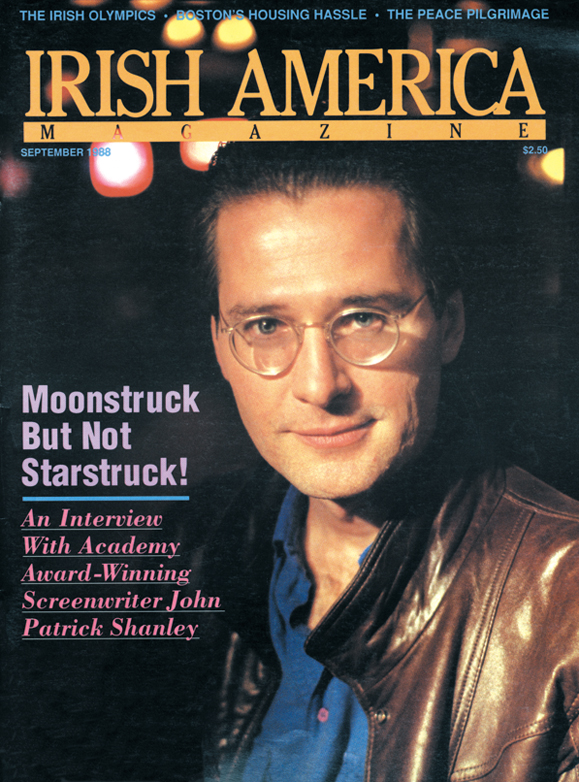

The gift of the gab, which translates into dialogue in his plays and screenplays, is one part of his Irish heritage that playwright John Patrick Shanley is grateful for.

℘℘℘

“I’ll take a funeral over a wedding any day,” declares John Patrick Shanley, 49, gleefully. The Bronx-born award-winning playwright, director and screenwriter, whose latest handiwork, Where’s My Money? was recently staged at New York’s City Center Theater, is quite vehement.

“I think this is an area where I’m extremely Irish. The very concept of death is something that we Irish find cheerful and relaxing.”

The mood description, cheerful and relaxed, seems to reflect his demeanor today as he sits in the theater’s bar area, dressed casually in a sea-green cotton shirt, blue jeans and scruffy white sneakers.

Lean and fit-looking, his boyish face beaming, John Patrick Shanley radiates a carefree exuberance that almost belies his serious and insightful perception of people and their relationships. Fortunately for him and us, Shanley sees the hilarity in even the darkest of these.

“It’s weddings that cause me horrible anxieties,” he reveals. “I find them grim affairs filled with people who seem to be in a sustained manic state. The wedding guests seem to be over-the-top cheerful, whereas at funerals and wakes everybody is talking in a normal way and properly communicating with each other and it’s all just lovely.”

If Shanley comes across as a tad eccentric, his resumé in the program for Where’s My Money? marks him as downright loony. Here it tells how he was thrown out of St. Helena’s kindergarten, banned from St. Anthony’s hot lunch program for life and expelled from Cardinal Spellman High School.

Not surprisingly, this pattern continued when was put on academic probation by New York University and instructed to appear before a tribunal if he wanted to resume his studies.

When asked why he had been treated this way by so many academic institutions, Shanley says he really has no idea. Changing the subject, he then tells how he went into the U.S. Marines. Shanley concludes his capsule bio in the program with a slight hint of proud defiance, reassuring the reader, “…he did fine and he’s still doing O.K.”

“Doing okay” is putting it mildly. For the enfant terrible from Archer St. in the Bronx is now reckoned to be one of America’s most original and gifted playwrights and screenwriters.

Ever since his breakthrough with Danny and the Deep Blue Sea, Shanley has been delighting audiences with many more plays such as Italian-American Reconciliation, Four Dogs and a Bone, Psychopathia Sexualis and, now, Where’s My Money?

Also, he has enjoyed success as a screenwriter and director of films that include Five Comers which won a prize at the Barcelona Film Festival, Alive, Congo, and Joe Versus the Volcano. Shanley picked up an Oscar for his original screenplay for Moonstruck which starred Cher and Nicolas Cage.

While Shanley’s work has brought him much critical acclaim, he particularly treasures the award he won from fellow screenwriters, the Writers’ Guild, for Moonstruck. They appreciated, as writers, his very special talent for creating believable dialogue that makes his characters seem so real while placing them in eccentric and wildly funny situations.

When one suggests that his bio reads more like a zany sketch for Monty Python than the real life experiences of a young lad raised by hardworking Irish parents, Shanley lets out a shriek of laughter. “That bio material is absolutely accurate,” he affirms. “I was thrown out of everything. With all the Catholic mythology that I was raised with delineating what was bad and what was good, what was allowed and what was forbidden, it was very difficult to toe the line. I tried very hard, but at being good, I was a miserable failure,” he concedes, “…and every step of the way I felt totally misunderstood.”

Shanley once wrote that as a writer and a man, his one central struggle in life was to accept who he really was. At one time or another, Shanley admits, he has denied every aspect of himself — the Bronx origins, his parents, his being American and his Irishness. Asked which part of him he feels is his Irish self, John describes his heritage.

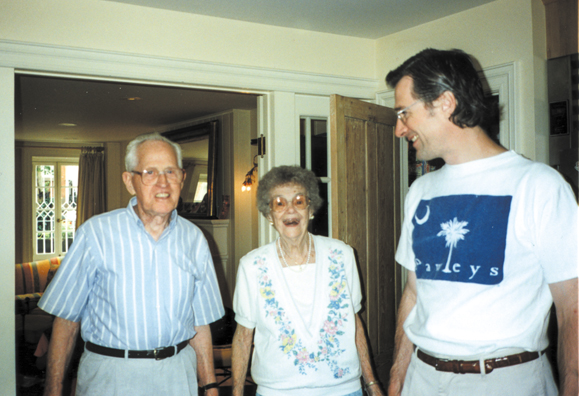

“My father didn’t come over to America until he was twenty-four. He was from a farm that still belongs to my family in County Westmeath, about eleven kilometers from Mullingar,” he explains. “I love to go there and I’m very close to that side of my family. My mother is a Kelly. She is first-generation, born in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. Her parents were from Ireland, of course, so I’m really Irish on both sides all the way back to infinity, I guess.” He smiles.

“When I was growing up I noticed that in Irish households, mine in particular, food was not dwelt on, nor was clothing nor any of the other sensual parts of life, but,” he emphasizes, “where the joy of life was concerned it did come out in conversation.”

He recalls warmly, “My father had the gift of language so I was born with that. He just passed away at age ninety-five and had dementia but he was as funny and Irish at the end as he ever was.” Shanley is philosophical. “He just didn’t know who I was, but he knew me long enough to suit me, so it was all just fine.”

“When my father first came over here he started working in the shipyards and then moved into meatpacking,” says Shanley. “He was one of those little Irish guys, wiry and very strong. Even at 95 when he shook your hand you felt it,” laughs Shanley with pride.

“He was extremely affectionate and he shouted across any divide, yelling in a voice that was much louder than you would have wanted for intimate conversations, especially when he was being fatherly. He would holler across the room at any given moment, `I loves yer, boy!’ He was the most confident man I’ve ever known, absolutely delighted with himself and everything he did. I never saw a moment of self-doubt in him. Never! My father loved to work. He’d work on his house on weekends. His idea of a vacation was to go to the farm and work in the fields,” laughs Shanley. “His whole thing was work.

“My mother, although she had a first-class mind, could be quite cool, not as overtly affectionate as my dad. She wasn’t supportive of my being a writer,” he recalls, “and my father wanted me to join the Sanitation Department even when I was graduating valedictorian from my class at New York University,” Shanley comments.

Suddenly sitting bolt upright, he announces, “I think I was born different from my parents or my siblings. I am the youngest of five, two brothers and two sisters, and I always felt different from all of them.

“I didn’t really know I existed until I was fifteen years old,” he describes his epiphany. “I was always in so much trouble. I’d been thrown out of school and was walking home to tell my parents the bad news, when I caught sight of my reflection in a shop window. I stopped, looked and spoke to myself. I said `If you and I can get along with each other, then everything will be O.K.,’ and I smiled at myself and made that little deal, right then and there, and from that time on everything has been just fine.”

While Shanley felt different from the rest of his family, he proved to be unique among the rest of the neighborhood, too. “As far as I know, not one parent or child out of all those people I grew up with in the Bronx went into the arts,” says Shanley, who had already started to write regularly by the time he was eleven.

“I honestly think that I had some genetic predisposition to be, not simply a writer, but a playwright,” he emphatically asserts. “From the time when I was very young I used to watch a lot of movies on television and I would think to myself, `Now, that’s a very interesting movie, much more interesting than all those other movies,'” recalls Shanley.

“And the ones I liked always turned out to be adaptations from plays,” he explains, such as The Devil’s Disciple by George Bernard Shaw or musicals like The Pajama Game that were transfers from Broadway. It wasn’t just the songs, great stuff like `Steam Heat’ that I loved, but, even more, I loved the dialogue in between. Probably because it was stage dialogue and I had never been to a theater at that point. I became accustomed to stage dialogue from television.”

Asked what the fascination was about that genre of writing, Shanley explains, “It’s a heightened, compressed way of speaking, it’s dramatic dialogue that’s set up just for the stage.”

Being a bright, perceptive young man, Shanley focused his acutely tuned ears and razor-sharp mind on his surroundings, absorbing the intricacies of people’s complex lives and relationships. His writing has always been inspired by those around him.

“The East Bronx was a mixed Irish and Italian neighborhood so I was exposed to all these Italian households as well as my own very Irish family,” recalls Shanley, “and I was very aware that, in these Italian homes, they were eating much better food than I was,” he laughs. “And these Italian guys actually thought about what they were wearing.” His eyes widen in mock amazement. “We never thought about clothes, the guys in my house.

“Also, the Italians would talk openly and frankly about sex,” his face lights up, “and they seemed to think that it was a good thing.

“I wanted what they had going on. I had my Irish strengths but I wanted all that other stuff, too,” Shanley laughs. “So, I wrote a lot about the Italian Americans.”

After serving in the U.S. Marine Corps, during the dying days of Vietnam, but stationed in Panama and Cuba, Shanley returned to New York University where he graduated Valedictorian.

Shanley took various jobs including bartending to subsidize his early writing career, and he also met and married a beautiful young Irish-American girl, Joan O’Neill. “We were both really children. I was 22 when I first moved in with her and we both had bits of trouble in our pasts. So as we got older, those things would come out and cause more problems,” reasons John. “We divorced in 1982.”

Looking back at his first marriage and those times, Shanley gets philosophical. “I think that if I had been well adjusted, gotten married and it had all gone just fine, then I probably would never have written any of the things I did.

“The difficulty was that I was having problems with my relationship and I was forced to give it some attention; to look at the problems and try to understand what I wasn’t doing right or the other person wasn’t doing right. You get provoked into thought. You seriously think about the things that are messing up your life. A lot of it had to do with the fact we were struggling. You know, affluent times in a country don’t lead to a lot of soul-searching, it’s only when the shit hits the fan that people suddenly sit up and take notice.”

For Shanley, his own soul-searching took him down the path of psychiatry expert Carl Jung. “Therapy was never a big thing for me. What was, was reading books. I read practically everything that Jung ever wrote and I applied them to my own life,” he explains.

“I wasn’t reading these books to become a better writer but to become a happier person, to try and solve my problems.”

Shanley admits, “I was in inner conflict about a lot of things. I certainly was raised with a clear idea of what a good person ought to be, and I didn’t feel that I fit that picture at all. So, I guess you could say I was at war with myself.”

Was he referring to his Catholic upbringing?

“I was from a very solid, predictable Roman Catholic household that ran like a clock. My parents were very religious.” Shanley describes it all. “We said the rosary every Friday night on our knees in the living room. My father went to Mass several times a week and slept with a rosary underneath his pillow. He did not, however,” and here Shanley is adamant, “talk about religion or proselytize.”

How does he feel about his religion today?

“I am not at all properly Church Catholic now,” he asserts, “but I do pray and I do believe in a divine force. I say grace with my children, but it’s not the grace I was taught as a child. There is a difference. One is grace filled with dogma and the other is a heartfelt thanks for our food, our lives, and Frankie’s, my son’ s, success in his spelhng test…that sort of thing,” he laughs. “It all gives me some solace and connection with God. I also think that a lot of the mythology of Catholicism is very good. It reflects real human experiences and it shouldn’t be forgotten for just that reason. I think you have to make some sort of distinction between embracing dogma and properly using the extremely rich Greek, Roman, and Catholic history and, yes, mythology that’s all so wonderful.

“It’s not about nothing — it’s about real human truths, but you can never let some institution like the Catholic Church claim a monopoly on the truth. You must never let anyone take away the significance of your own life experiences,” he decides.

“Each person has sovereignty over themselves that has to be respected. You can’t bend other people to your own will, even if you think you know what will make them happy. It’s their life, they’ve got to deal with it. There’s that great line from Dickens, it’s the opening line of David Copperfield, `Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show.’ It’s just beautiful and I think about that line a lot. I’ve certainly been the hero of my own life so far, but when the story is finally told, I have no idea what an objective verdict will be.

“I believe in redemption, I believe in many of these Catholic notions. I believe in the power of confession. I think that if you tell someone about your misdeeds you feel better, that you’ve got to let it out; especially if you’ve done something really bad. You’ve got to tell somebody,” Shanley is adamant.

Does he go to confession?

“Oh, no, I don’t go to confession. I’d tell the corner news dealer before I’d confess to a priest.”

Speaking frankly, Shanley reveals a certain pugnacity during his early days. “I’d come home from school with blood running down my face and my father would look at me and ask, `What happened to you?’ and I’d reply, `I got into a fight.’ Then Dad would ask, `Did you win?’ and I would answer, regardless of the truth, `Of course, I did.’ I knew the right answer,” he laughs. “And my father would say, `Good boy,’ and that was the end of it.

“We discuss his work.

It was not until 1984, when he was 32, that Shanley had his first `hit.’ Although some of his earlier work had been put on in rather obscure venues, it was Danny and The Deep Blue Sea starring John Turturro and June Stein that first brought him critical acclaim when it was staged at The Circle in the Square Theatre in Manhattan.

Shanley believes that if everyone would speak their mind, everything would be a lot better for most people, and that philosophy has molded his playwriting. “I didn’t know that at first. I was afraid that if I said honestly what I felt, the world would gang up and kill me,” laughs Shanley.

“It turns out that every time I said what I actually thought, everything got better.”

And it’s this seam of blatant and often brutal honesty that runs through the provocative face of Shanley’s body of work. His latest play, Where’s My Money? is no exception. Written and directed by Shanley, originally for the Labyrinth Theater Company, it’s a dark comedy that deals with all the insecurities of marriage with such force that many in the audience squirm in their seats.

I asked if Where’s My Money? is about his second marriage to the actress Jayne Haynes, whom Shanley married in 1986, and who has appeared in several of Shanley’s plays including Italian American Reconciliation and Beggars in the House of Plenty?

“No,” insists Shanley, “this play is more about the institution of marriage, itself, and these relationships between women that interests me so.

“Funny you should mention Jayne,” he then announces. “Jayne and I are going through a divorce right now. In fact, I’m off to sign the divorce papers this afternoon.”

Shanley reassures, “We’re still very close friends and we have two nine-year-old boys that we adopted at birth, just four months apart. We named them Nicholas and Francis after my parents,” he adds jovially.

With two failed marriages behind him, one wonders what attracts him to women in the first place. “Well,” he replies, “I’m usually turned on by intelligence…sexiness and intelligence! A good sense of humor is a nice thing, too, but I guess I’ve never been with anyone who wasn’t very smart. Looks don’t seem to enter into it too much.

“Along the way I did adopt, in retrospect, a rather bizarre strategy.” Shanley laughs. “The first came with the realization that the kind of woman that I’d been attracted to was a disaster for me. I decided that I was going to have to avoid women I found attractive. So I decided to zero in on women that I didn’t find attractive. I’d look around at parties and think, `Who here doesn’t interest me at all?’ I’d then go over and strike up a conversation with that turkey.” Shanley grins. “That, as you might expect, didn’t work.”

“The other approach,” Shanley recounts, “was quite sensible. I decided they should be good looking.” Asked if he had any hobbies or pastimes, Shanley replied that he was not unlike his dad. “I do a lot of different kinds of work, you know. Right now I’m doing a musical version of Moonstruck. I’m more than halfway through it. Henry Kreiegar who did Dreamgirls and Sideshow is doing the music and Susan Birkenhead who did the lyrics for Jelly’s Last Jam about Jelly Roll Morton is doing ours. I’m writing the book.”

Talking about other playwrights he likes, Shanley says, “I’m a huge Shaw fan and another of my favorite playwrights is John Millington Synge. His Playboy of the Western World has always been one of the most unforgettable because of its extraordinary celebration of language, and its humor is just my humor. When I went to Ireland for the first time, sometime in the 70’s, I went immediately to the Abbey Theatre to see a production of it,” John recalls fondly.

“But now what I do when I get to Dublin airport is to get a rented car and go straight to the family farm. It was my Aunt Mary and Uncle Tony’s place. They lived there until they died a few years ago. Some of their children lived with them on the farm, another child lived just clown the road and two others lived a few miles away. The interesting thing to me was, first of all, everything those two old people said was memorable, in fact, publishable.” John says wistfully, “It was beautiful and rather incredible. I did pretty much nothing but take notes the whole time I was there with them, and I never take notes about anything,” Shanley insists.

“I wrote down everything they said because it was so fabulous. Then, the last night before I left, they threw me a little hooley and my Uncle Tony said, `You’ve been writing in that little book all week; could you read out a bit of what you have been writing then?’ So I read back to them what they’d been saying all week and they had the grandest time, heating themselves; they took such delight. Uncle Tony had tears running down his face, wiping them away with a handkerchief.

“While it was the old people on the farm who spoke the most beautifully, the people from down the road, about a mile away, spoke the next most beautifully. It seemed the further away from this farm people lived adversely affected their conversational poetry. Except for me! When I went to that farm in County Westmeath for the first time in my life, I thought, `I’m home! These people talk like me. We can have real conversation.’ That was very special to me.” ♦

Leave a Reply