Although she takes her husband’s surname, Ali Hewson has always shied away from publicity generated by marriage to rock star Bono, the frontman of U2, and while he carries on his war against world debt, she concentrates on nuclear fallout closer to home.

℘℘℘

Anna Gabriel is excited. Having changed from her customary jeans and T-shirt into a velvet frock the nine-year-old is all dressed up for a party to commemorate Chernobyl. The nuclear disaster happened seven years before Anna was born but Chernobyl’s 16th anniversary has a strange significance for her. Genetic damage from radiation exposure suffered by her mother left deformities in Anna’s legs, ears and fingers. Like thousands of afflicted babies in Belarus she was abandoned at birth.

If her life changed long before she entered the world it changed for the better nine months after she was born. Adi Roche and Ali Hewson of the Chernobyl Children’s Project visited Abandoned Children’s Hospital Number One outside the capital, Minsk. As the Irish women moved around the ward comforting the children, many of whom bore deformities directly related to radiation, Ali noticed a particular baby smiling at her from a nearby cot. She reached in and took the the infant in her arms.

Every time Ali returned to Belarus with the Project she found Anna waiting for her. The child was distraught at each parting but four years after the initial visit, Robert and Helen Gabriel form Bandon, County Cork set about the highly bureaucratic process of bringing Anna back to Ireland for adoption. For over five very happy years the exuberant Anna has grown up alongside half-sister Clodagh as through the two were twins.

Anna’s shin-bones have not developed. In time she will face major surgery, possibly amputations, to alleviate the pressure on joints between her knee and ankle. Whatever lies ahead she has prospered in a loving environment and there’s no looking back.

And so when the Gabriel family planned to travel to Dublin for the anniversary Anna was thrilled at the prospect. Not only would she get to go to the party but she would meet her godmother, the dark–haired woman who lifted her from the orphanage cot eight years ago.

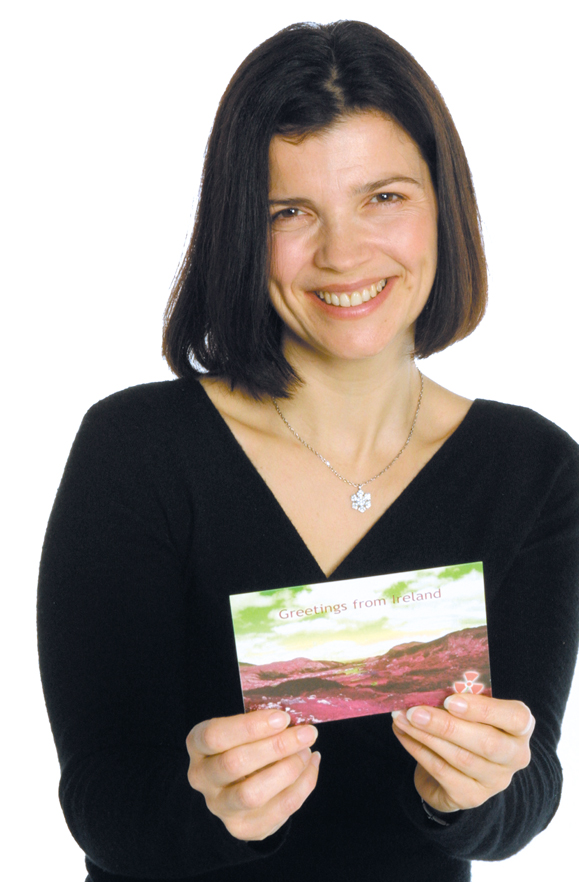

Ali Hewson is in the spotlight. It’s an unusual role fro the 41-year-old but she’s handling it with ease. Although she takes her husband’s surname she has always shied away from publicity generated by marriage into rock superstardom. Ali and Bono, the frontman of U2, first met in Mount Temple School on Dublin’s north–side, married in 1982 and now have four children.

It was in 1993 that Ali got involved with Chernobyl Children’s Project Ireland. While some of her contributions have been high–profile – such as presenting the documentary “Black Wind/White Land” or raising funds through celebrity fashion shows – her work with the Project is less patron saint than helping hand. She has visited Belarus on eight occasions but it is the possibility of a nuclear disaster closer to home that catapults her into the limelight.

The Chernobyl commemoration takes place at Dublin Corporation’s modern city offices at Wood Quay, beside the River Liffey at Christchurch. The evening marks the beginning of a month-long photographic exhibition depicting the struggle in which the Cork-based Project is engaged. Magnum photographer Paul Fusco’s collection of large black and white images offers a moving, if not frightening, reminder of what happened in the former Soviet Union.

The exhibition was made possible by assistance from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Project founder Adi Roche leads former Minister for State Liz O’Donnell on a guided tour. Anna and Clodagh are thrilled to be the center of attention while waiting staff serve drinks and sandwiches. Anna takes a break from demolishing a bottle of soda when introduced to the minister.

Guests are arriving steadily and homeward–bound Corporation workers are curious about an event that brings so many movers and shakers to their workplace. They recognize Adi Roche and Liz O’Donnell but their attention is drawn to a glamorous dark–haired woman arriving at Wood Quay. She has just finished an interview with Radio Cumbria explaining why she wants to see Sellafield’s nuclear reprocessing plant shut.

Adi Roche and Ali Hewson meet as close friends committed to the cause they lead. With O’Donnell they form a lively trio when suddenly their discussions are torpedoed by a beaming child in a black velvet dress. Spotting Ali across the room Anna races in uneven strides to her godmother. Ali sees the child coming and swoops to pick her up in an affectionate, heartfelt embrace. Press photographers move to capture the moment but this is no stage–managed “photo–op.” The paparazzi intrusion is borne without notice or complaint. If celebrity is a by–product of the modern age it just comes with the territory when you lend your name to a charity organization.

The snapshot of Ali and Anna brings to mind the innocence and vulnerability of children, and the image is eloquent shorthand to how the campaign against Sellafield, the British nuclear plant, came about. This is no overnight conversion to the nuclear issue. Ali Hewson has been involved in Greenpeace for years, long before the Chernobyl Project. In 1992 she enlisted U2’s help in highlighting the environmental impact of discharges from the Sellafield plant. Dressed in white anti–radiation suits, all four band members were filmed with Greenpeace activists beside drums filled with contaminated mud from the Irish Sea.

The Hewson family home on Co. Dublin’s Killiney coast lies southwest of Sellafield, the radioactive jewel of British Nuclear Fuels Ltd. (BNFL). The Sprawling plant in Cumbria put out a reactor fire in 1957 (when known as Windscale) and has since withstood a number of lesser accidents as well as several prosecutions for falsifying maintenance and safety records.

As a mother of four Ali Hewson’s Belarus experience brought the nuclear threat into sharper focus. “I started to wonder how safe it was for them to play on the beach or swim in the sea or even to eat fish,” she explains. “This is a nuclear–free land and yet if anything happens to that plant, the East Coast of Ireland is straight in the firing line. I’ve always felt strongly opposed to Sellafield. It is 60 miles away from the Irish Coast. It is pumping two million gallons of radioactive liquid waste into the Irish Sea everyday, making it the most radioactive sea in the world. If an accident happens at the plant, or if there is a terrorist attack, depending on which way the wind blows, Dublin, Dundalk, Droheda, Belfast, and vast parts of Ireland, would be uninhabitable forever.”

What concerns her is the very real possibility that Chernobyl could happen again. “I have seen children born with deformities and dying in orphanages. Children who have had their thyroid glands removed and will need to take medicine for the rest of their lives – if they can get it. And because radiation doesn’t not respect borders, in Ireland we are in the same position as Belarus. We did not ask for this nuclear power base to be built beside is, but we are just as vulnerable as the people of Britain.”

It’s an intrusive comparison. Chernobyl is actually situated in Ukraine, but following the 1986 disaster a northerly wind blew 70 percent of the fallout over neighboring Belarus. That a nuclear–free country is the biggest victim of a nuclear fallout argues its own case. “That is exactly what could happen to us,” says the social science graduate.

September 11 sounded alarm bells to Sellafield as a potential terrorist target. The British response was mind-boggling. Rather than scale down operations, BNFL announced plans to open a new MOX (mixed oxide fuel) plant at the site. “I’m not surprised,” she says, seeing the BNFL move as a profit–seeking gambit for a loss–making enterprise. “They want to expand its operations and the Irish notion even in the debate.”

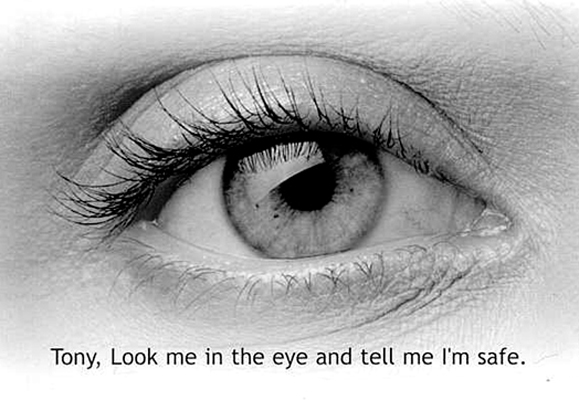

And so in an effort to seeing public opinion against Sellafield Ali Hewson decided to bombard Britain with postcards. Using an idea inspired by Dubliner Michael Carroll and with assistance from An Post, the Irish postal service, a stamp–addressed postcard was delivered to every Irish home in Ireland. Recipients were invited to sign the card and post it to either the British prime minister with the message “Tony, look me in the eve and tell me I’m safe,” to Norman Askew, chairman of British Nuclear Fuels (“Tell us the truth”) or to Prince Charles, regarded as an influential environmentalist, who got a radioactive shamrock saying “Wish you were here?”

The response is overwhelming. An estimated 1.6 million cards were posted across the Irish Sea. “An amazing reaction,” Hewson enthuses. The take-up represented 93 percent of Irish households responding to the campaign. In an age of cynicism and apathy it certainly was staggering.

Under such an avalanche of public opinion the issue was suddenly too big t ignore at cabinet level. In the House of Commons British Prime Minister Blair acknowledged the extent of public concern in Ireland.

Minister for Energy Brian Wilson suggested the appeal was “generalized and emotive,” but stock responses from Westminster and BNFL were of little interest to the campaigner who personally delivered the first card to 10 Downing Street on April 26.

“What we want to do is raise awareness in Britain, enough to make it an election issue,” she feels. “People in the UK were more interested and more concerned that I expected. I think they realize Sellafield is a reprocessing plant collecting nuclear waste from all over the world.

“This campaign isn’t about the ethics of nuclear energy. It’s about reprocessing and having a nuclear dustbin on your doorstep. BNFL promises to cut the daily two–million–gallon discharge within 20 years, but if they land international MOX contracts to extract uranium and plutonium from nuclear waste, the risks increase and further pollution is inevitable.

This is one for the long haul.

The case has already been taken over by four people in Dundalk, Co. Louth. Over seven years ago the Stop Thorp Alliance Dundalk (STAD) campaign came into being. In taking a legal case against BNFL the group will also challenge the Dublin government on its record for protecting Irish citizens. STAD claims that incidence of cancer is abnormally high in the Carlingford area of Co. Louth and there is a direct relation between the illness and emissions from Sellafield. to date the Irish government has provided €400,000 towards technical assistance but the action group has received no support for legal fees. As a result STAD will take a case both against BNFL and the Irish government at the High Court in Dublin, while in a complicated legal turn, the Irish government will take on BNFL over the MOX issue.

“All you have to do is take an interest in Sellafield or the nuclear industry and you’d be worried,” said a STAD spokesman. “If storage tanks over there went belly–up it would empty this country. Ours is primarily a legal campaign rather than a political campaign, but the postcard idea has certainly raised public awareness in Ireland.”

“I’ll stick with this for as long as Sellafield is there,” pledges Ali Hewson. “We will try to close down Sellafield, or at least close down its’ activities. I would prefer not to do it,” she adds, preferring to work behind the scenes if she could. But she’s made her choice and on balance can live comfortably with her decision.

“There is a price to campaigning like this but it’s worth it,” she feels. “I think our family probably has enough publicity as it is and I would prefer to keep a more private life, but in the end I felt I couldn’t turn round to my children in twenty years’ time and say that I had had an opportunity to do something about Sellafield but didn’t. I have seen what happened in Chernobyl, and there is no way I am going to let that happen here.” ♦

Leave a Reply