The hotel lobby buzzed with conversation. Irish inflections mingled with accents from New Zealand, Australia, England, Canada, and various parts of the U.S. And above the hum the name would grab my ear.

“McNamara.”

“McNamara.”

As a reflex, I’d ram. And almost instantly smile and shake my head, laughing to myself at how often I kept doing that. Back in America, if I heard my last name uttered in a crowded room then someone was talking to me or about me. But this was the town of Ennis in the county of Clare, in a space crowded with dozens of McNamaras happily gabbing about being McNamaras. From all over the globe we’d returned to ancestral territory in May 2002 for the first MacNamara Clan Gathering (the name is spelled as Mac or Mc, and no one seems to worry about why).

When I first heard that a MacNamara Clan Association had been formed in Ireland and was planning a big gathering of Macs, I was, to be honest, skeptical of the entire idea, though I do have an interest in family history. Less than three years ago my father and I decided to finally construct a reliable family tree, and after finding my father’s father listed as a 12-year-old “scholar” living in a farmhouse in the returns of the 1901 Census of Ireland we continued burrowing deeper into microfilms of records we could borrow in America.

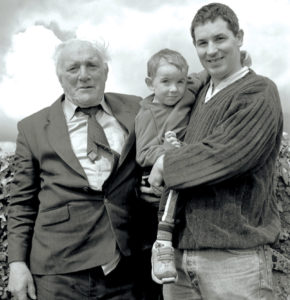

Within a few months we had traced members of my father’s family back to 1816, when the written records in the parish of Quin began. And on our first trip to Ireland, in April 2000, we not only were able to visit the exact place where the family had lived, but through some fortunate encounters with neighbors and extremely distant relatives, we even discovered, in a Clare farmhouse, family snapshots of my father and his siblings as children. The photographs had been mailed to Ireland from Paterson, New Jersey in the 1930s by my grandmother, who maintained a correspondence with my grandfather’s sisters who had stayed in Ireland.

In subsequent trips to Clare I collected stories about my great-grandfather, who is vividly remembered by elderly residents, and our family in America became friends with citizens of the townland my grandfather, John McNamara, had left in March 1904.

After such heartening experiences, I simply wasn’t sure what the point would be to attending something billed as a “clan gathering” of McNamaras. I feared the event might turn out to be some St. Patrick’s Day party misplaced in time and place, a trite “Oirish” spectacle for the benefit of Irish-American tourists.

My apprehensions turned out to be entirely wrong.

A few weeks before the event, I happened across an article about the clan gathering while reading the online edition of the Clare Champion, a local Irish weekly. I was surprised and impressed by what the MacNamara Clan Association in Ireland was planning. Family members had been talking about taking a trip to Ireland later in the year, and after some fast phone calls to Clare our trip was hastily rescheduled and we were off to meet the assembled McNamaras.

Arriving in Clare a few days before the clan gathering was to begin, we were visiting out in the countryside and soon discovered that the impending invasion of McNamaras had somehow reached mythical proportions. “Some say there’s 5,000 of you coming here,” was the forecast received in a pub in Quin.

Monday night’s welcoming reception gave us a chance to meet a number of local McNamaras, all of whom were delighted that members of the clan — though less than a tenth of the rumored 5,000 — had arrived in Clare from all comers of the earth.

The week quickly turned into an enjoyable blizzard of activity. Historical lectures began with a morning spent with Irish historian and broadcaster Kieran Sheedy, who related a lively chronicle of the McNamaras beginning in the distant centuries when they first emerged as a powerful family controlling most of East Clare, alternately battling or making peace with their perennial rivals, the O’Briens. As we took seats for the historical overview, the idea that we are somehow a distinct clan with family resemblances even after all these centuries was evoked when a woman approached my father and said, “I have to ask where you’re from, because you look exactly like my father in Canada.”

Afternoons were devoted to bus tours to sites of historical interest in Clare, with natives riding along to provide local color. Energizing our scenic ride through West Clare was Brother Sean McNamara, a Christian Brother who devoted himself to teaching and the study of botany though he might have also enjoyed a fine career as a stand-up comedian. Besides pointing out rains of tower houses and churches, Brother Sean related local legends, occasionally ending with a cheerful, “At least that’s the fiction, you’ll have to get someone reliable to tell you the facts.”

The Clareman accompanying the tour of North Clare, Michael McMahon, deftly wove together a narrative consisting of botanical details of the Burren’s unique “micro-climates” as well as historical notes on landmarks which included the 6,000-year-old Poulnabrone portal tomb, perhaps the most photographed landmark in Clare. A fellow with a true appreciation for literature, Michael quoted passages from poetry inspired by the Burren, including the English poet John Betjeman’s classic “Ireland With Emily,” which evokes the difficult yet gorgeous landscape in lines such as:

Stony seaboard, far and foreign,

Stony hills poured over space,

Stony outcrop of the Burren,

Stones in every fertile place.

At the tour’s conclusion, Michael gave an entertaining talk in Ennistymon on the branch of the clan native to northwest Clare, which included the famed bohemian Francis MacNamara and his daughter Caitlin, who became the wife of Dylan Thomas.

An enormous organizing effort by the MacNamara Clan Association in Clare had gone into producing a Wednesday night concert featuring performers who either carry the name or possess McNamara blood. Following the singing of the national anthem, Mary MacNamara and her brother Andrew, Tulla natives internationally known for their skill on concertina and accordion respectively, took seats onstage and performed a rambunctious set that could only be faulted for ending too soon. But there was no shortage of music, as the concert stretched into a marathon five-hour event, with singers, dancers, and musicians putting on a show Americans would simply never get to see at home. Noted singer Niamh Parsons, whose mother is a Clare McNamara, performed songs from her new album, young girls put on an awesome display of step dancing, and throughout the night youngsters from Clare thrilled the international visitors with their astonishing skill on traditional instruments.

The chairman of the MacNamara Clan Association, Peadar McNamara, who’s been known to sing in pubs with the Ennis Singers Club, performed the classic Irish-American sad song compiled from immigrant letters, “Kilkelly,” in which the “schoolmaster Pat McNamara” is mentioned. Achill Island’s John McNamara sang, in Irish, an absolute jewel of McNamara literature, “The Fair Hills of Ireland,” a lyric by the 18th-century Clare poet Donnchadh Ruadh MacNamara. It was a moving performance and a very rare treat, even for those of us who can’t speak Irish. To deftly lighten the tone and restore a festive mood, John was joined onstage by his twin brother Patrick to perform a hilarious old music hall song, “McNamara and O’Hara.”

As the week went on, banquets at local castles and a dinner dance filled the evenings, and late night visits to pubs might have reduced the attendance at historical lectures the following mornings. A half-joking request from the local Macs was that if any visitors should have too many pints and attract attention, “Please, tell them your name is O’Brien.” One Canadian reveler couldn’t possibly pin the blame on a rival clan, as he sported the McNamara coat of arms tattooed on his bicep.

“Some of the lads might have just come for a bit of the craic,” said one Irish organizer. “Nothing wrong with that, but we really wanted to showcase the culture and history.”

Throughout the week an American tour organizer armed with a credit card machine offered souvenir T-shirts as well as certificates on imitation parchment proclaiming that whoever filled in the blank was a member of the clan. It didn’t look like the merchandise was moving briskly, though price reductions and special deals for multiple purchases seemed to quicken the pace at week’s end. Photocopied fliers also appeared touting an American company that purports to establish genealogy not by searching written records but by testing the DNA of groups of people.

Saturday morning, May 18th, marked the historical and spiritual finale, a special Mass to mark the 600th anniversary of the founding of Quin Abbey as a gift to the Franciscan Order by clan chieftain Síoda MacNamara. The Tulla Pipe Band led a parade from the village church in Quin to a site overlooking the abbey, where assembled McNamara priests, local clergy, and Fr. Patrick Conlan of the Franciscans celebrated the Mass of thanksgiving. Brilliant young musicians from Tulla, playing fiddles and concertina, provided heartbreakingly beautiful music in the open air. A military salute to McNamaras who had fallen in the service of several nations followed the Mass, and an enormous carved stone marking the event, which will be put on permanent display at Quin Abbey, was unveiled.

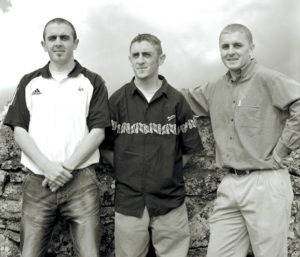

At a final reception on Saturday night, McNamaras from across the world were still marveling over physical resemblances, and perhaps everyone saw someone across the room who looked like an uncle, aunt, or cousin. Distant and difficult history had scattered us as far as we could possibly go, but as people took snapshots and exchanged e-mail addresses, it seemed that it couldn’t possibly take another 600 years for the clan to get back together. ♦

Leave a Reply