Bono wants a major rethink on U.S. foreign policy regarding Africa. The Dubliner and frontman for U2 feels that aid can work but only if the burden of debt is removed, and he took his argument to U.S. Treasury Secretary Paul O’Neill.

When Bob Geldof roused the Western world out of indifference about starvation in Ethiopia, much was made of the fact that he was Irish. The general wisdom suggested he understood the Ethiopian plight because he shared a folk memory of famine. The Dubliner insisted his response was purely humanitarian, but no one could deny that the Boomtown Rat was somehow following an established path between Ireland and Africa.

For most of the last century thousands of missionary priests and nuns left Ireland to proselytize for the Catholic Church. The situation has changed significantly in recent years. Skilled professionals still leave for Africa, but Irish aid workers no longer operate on religious grounds. They are less busy saving souls than saving lives.

Geldof’s high-profile campaign raised $200 million. It was a huge achievement that for a time opened minds without changing them. It was also a once-off event that enlisted celebrity support before compassion fatigue set in. Geldof and Live Aid became so synonymous that his moderately successful music career seemed dwarfed by the global catastrophe he’d taken upon his shoulders.

Celebrities might be persuaded to front particular causes but guest appearances are usually as far as it goes. In the showbiz world where sell-by dates come quickly, stars are urged to steer clear of political causes without ready solutions. Audiences want singers, not preachers; stars, not model citizens; entertainers who offer a chance to escape reality rather than confront it.

Perhaps it’s just a coincidence that after 15 years, Geldof’s baton has passed to a fellow Dubliner. Another rock star with an ego and a conscience. This time it’s not a one-day televised concert but an arduous campaign of lobbying and briefings on the corridors of power. Paul Hewson, better known as Bono, is following the trail.

The U2 frontman was part of the Live Aid effort in 1986, and the band’s dynamic performance at Wembley that afternoon marked a significant leap in U2’s international profile. Looking back, Bono credits Geldof for reacting “on a visceral level” to horrific TV images of famine in Ethiopia. Over the years he has come to understand that gut reaction is only part of the answer.

“I’m tired of dreaming,” says the father of four. “I’m into doing at the moment. It’s, like, `let’s only have goals that we can go after.’ U2 is about the impossible. Politics is the art of the possible. They’re very different, and I’m resigned to that now.”

At 41 he could be forgiven for relaxing in the afterglow of the `Elevation’ tour that relaunched U2 as a musical force. But there is a restlessness about him that doesn’t allow for basking just yet. And with remarkable stamina he’s become a persuasive lobbyist with an open-ended checklist.

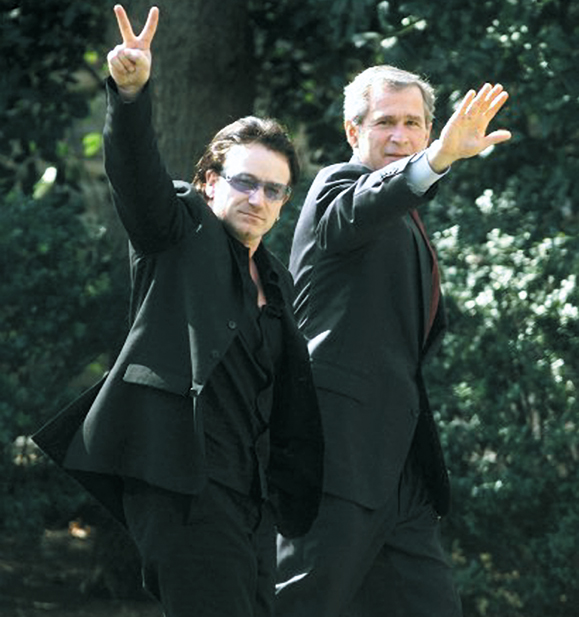

Millions of Africans have died from famine, malnutrition and AIDS through the 20th century. Assistance to date has been piecemeal and activists realize they must go to the very top if fundamental change is to happen. When Bono met with President Bush at the Inter-American Development Bank forum, it was not to try to soften the President’s Texan heart. He wanted a major rethink on U.S. foreign policy regarding Africa. The Dubliner feels that aid can work but only if the burden of debt is removed.

Bush was doubtful. Fellow Republicans — like his Treasury Secretary Paul O’Neill — felt the same way. The former CEO of Alcoa (the world’s biggest aluminium corporation) contended that aid has failed to produce results. Why throw more money at it when there’s nothing to show? Bono made an appointment to see O’Neill.

“I refused to meet him at first,” recalls the Treasury man. “I thought he was just some pop star who wanted to use me.” They were scheduled to meet for half an hour. The meeting ran 60 minutes overtime. “He’s a serious person,” decided O’Neill. “He cares deeply about these issues, and you know what? He knows a lot about them.”

President Bush suggested the pair go to Africa on a fact-finding mission. “When Bono and I met with him, he said to us, `You show me more results, there will be more money,'” says O’Neill. With their remit set somewhere between advocacy and skepticism, the singer and the secretary were on their way.

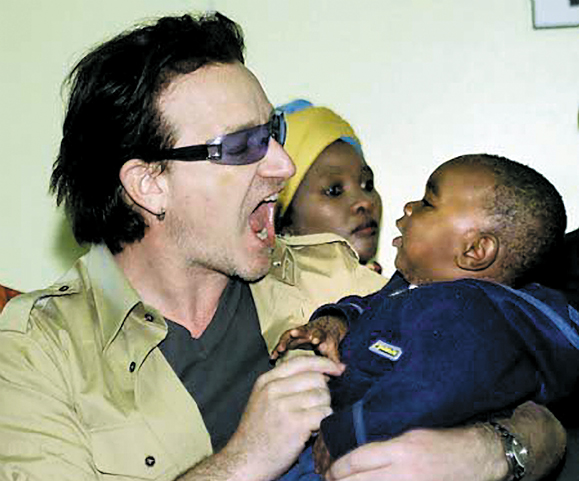

The image of rock star Bono and the 67-year-old U.S. Treasury Secretary hustling around Africa proved irresistible to the world’s media. Dubbed “The Odd Couple,” the two covered a lot of ground on their 10-day trip. They visited Uganda, South Africa, Ghana and Ethiopia for a close-up view of aid-in-action, where it has worked and failed, as well as meeting with influential players in development economics.

“I think Paul O’Neill is going to be a very different person going out of this trip than he was coming in,” Bono told Time after visiting an AIDS clinic in Soweto. Unlike Irish missionaries of the past, Bono didn’t aim his persuasive skills at receptive Africans. Instead, he set about converting his American traveling partner.

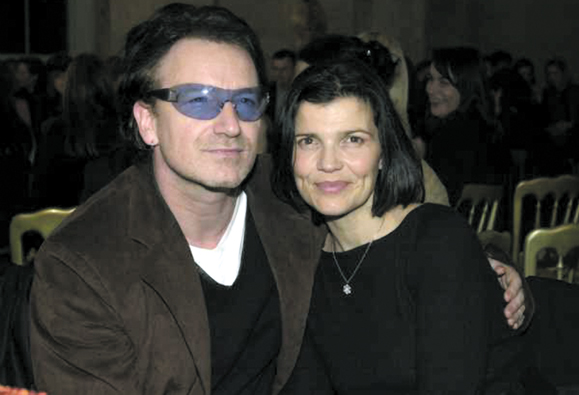

Bono’s involvement is no day-trip into the political arena. Never shy to air his politics onstage, he regularly endorses causes like Greenpeace and Amnesty International. Following Live Aid in 1984 he and his wife Ali went to famine-stricken Ethiopia to work for six weeks at an orphanage. The experience left its mark. “You’d wake up in the morning, and mist would be lifting,” he recalls. “You’d walk out of your tent, and you’d count bodies of dead and abandoned children. Or worse, the father of a child would walk up to you and try to give you his living child and say, `You take it because if this is your child it won’t die.'”

As a 15-year-old growing up in Dublin he lived through his own tragedy. His mother, Iris, suffered a brain aneurysm while attending the funeral of her father. During his teenage years at Mount Temple School — where U2 formed 26 years ago — he joined a Christian prayer group, Shalom. He subsequently left, but his abiding fascination with scripture is frequently reflected in his songwriting.

U2’s northside chapel has become more of a global cathedral, and the group ranks as one of the world’s most successful rock bands. Millions of album sales and numerous world tours later, the singer saw that the suffering which inspired Live Aid had not gone away. He added his voice to the Jubilee 2000 campaign, which targets the $350 billion foreign debt afflicting 52 of the poorest countries in the world. It means that for every $1 in assistance, $9 comes back in loan repayments.

“As a pop star I have two instincts,” he explained. “I want to have fun, and I want to change the world. On New Year’s Eve ’99 there was a chance to do both.” Referring to Live Aid, Bono recalled, “We raised $200 million and we thought we’d cracked it. It was a great moment, a great feeling. Then I discovered that Africa pays 200 million dollars every five days repaying old debts. Tears were obviously not enough.”

The more Bono discovered about the imbalance, the more he committed himself to doing something about it. “The millennium is a key moment in time,” he noted with a biblical flourish. “We have to grasp that moment — the rule of money-lenders has gone too far.”

The position was echoed by the Wall Street Journal, describing loan fees on poor nations as “obscene.” Traditionally conservative voices — such as the Adam Smith Institute and Harvard economist Jeffrey Sachs — argued that Africa’s debts had become so top-heavy they crippled any chance of breaking the poverty trap.

Bono consulted with Sachs and set up DATA (Debt, Aid and Trade for Africa), an agency based on the U.S. Marshall Plan, which canceled European debts after World War II and provided trade incentives to rebuild their economies. “He gave a call and said he’d like to meet and talk about foreign debts,” says Sachs. “And he said to bring a conservative colleague with me, because he wanted to hear the other side.”

The lobbying began. “I’ll never forget one day during my Administration,” says former President Bill Clinton, “(Treasury) Secretary (Lawrence) Summers comes into my office and says, `You know, some guy just came in to see me in jeans and a t-shirt, and he just had one name, but he sure was smart. Do you know anything about him?'”

Jubilee 2000 renamed itself Drop The Debt. The song remained the same, and the singer, restored to superstardom with the global success of U2’s 12th album, All That You Can’t Leave Behind, began knocking on doors. He managed this despite another grievous personal setback. His father, Bob Hewson, died on the eve of the group’s massive concert at Slane Castle in Co. Meath. The show went ahead, dedicated to his father’s memory.

“I’m in the music business, the volume business,” Bono once remarked. “Making a lot of noise is something musicians do well. We see a chance here, for an idea that will give not just the millennium some meaning, but also our generation.”

Meetings were arranged with known figures like Clinton, Kofi Annan, Tony Blair, Pope John Paul II, George Soros, Jesse Helms and Colin Powell.

Other powerful figures might have a less public profile, and so last year Bono showed up at the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum. At a late night discussion in a New York restaurant he joined a table of diverse interests including the Bill &Melinda Gates Foundation to discuss how America might be persuaded to see the benefits of letting Africa stand free. He told them he had earlier in the day met with 30 Congressmen. “I am not willing to give up on the Republicans,” he insisted. “They’re tough, but they’re willing to listen.”

Paul O’Neill, who is himself of Irish ancestry, indeed proved willing to listen but tough. He and Bono differed publicly on a number of occasions, but the tour partly fulfilled its purpose by putting development aid squarely on the agenda of Congress. O’Neill might be slow to change but he was not unmoved by what he saw. “There is an essential question when I see real people sitting here with us and know that there are thousands who are not getting any treatment,” said the Secretary at the Soweto AIDS clinic. “It is pretty hard to sit there and see this kind of courage and not know that the world needs to respond. If you just sit and talk for an hour with these wonderful people and hold their children, no one can say no.”

They were sentiments that could have been expressed by his traveling partner. Bono noted during their 10-day tour that 55,000 people died from AIDS, 14,000 children were born with HIV, and Africans spent $400 million on debt payments.

The very scale of adversity would be enough to make most people give up but Bono’s missionary impulse is urgent and pragmatic. “So,” he asks, “what can we do?” ♦

Leave a Reply