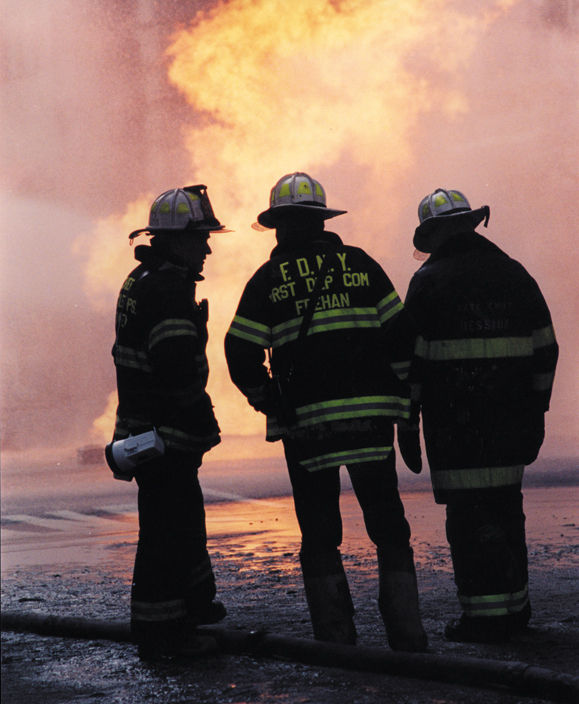

When the dust settled on September 11, one of the 343 firefighters listed as missing, later pronounced dead, was Chief Bill Feehan. A firefighter to his core, Feehan was loved by the men and women in the FDNY.

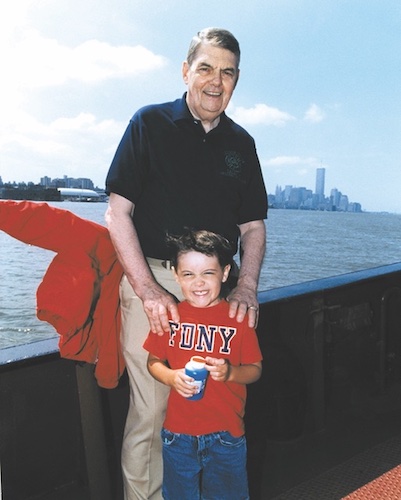

Bill Feehan loved eggs over easy. Every day for the last 20 years at least he stopped at the Northern Cross Diner in Queens and read the Daily News as he had his usual breakfast of two eggs, toast, hash browns and bacon. He also loved Shepherd’s Pie, was a sucker for a good crumb cake and on occasion enjoyed a sip of scotch with the boys in the office unwinding after a hard day. He loved to hear from his sons and daughters throughout the day as they checked in with him on dinner plans. They mothered him since the death of his beloved wife Betty in 1996 and made sure he ate right, did his laundry and stayed on him about paying his bills on time, which is a whole other story. They regaled him with the latest exploits of the grandchildren and sent them along for those precious rides on the fireboat with Grandpa.

You could hear him greeting son Bill with the enthusiastic “Guillermo” every time he called. He loved the fact that son John was in the busy Squad Company 252 in Brooklyn and son-in-law Brian was in Ladder 120, because it gave him direct sources for what was going on in the field. His eyes would light up every time Chief Medical Officer Dr. Kerry Kelly walked in his room, and he waited with a grin as she attempted to argue on behalf of one of her long-term problem cases. It was usually a firefighter with injuries so chronic he should have been retired years ago but couldn’t face leaving the job he loved so much. Dr. Kelly had squirreled him away doing paperwork somewhere and had been found out and now had to make the case to keep him on so he could qualify for his 20-year pension. Bill Feehan would play the tough guy, make her squirm, tell her “No, he has to go,” then undo it the minute she left the office, securing a future for the fire fighter and his family.

As you drove through the City with Bill, the vastness of his experience revealed itself. :This is where we had a big job, three floors of fire,” he’d say as he pointed to a loft in Soho. Hell’s Hundred Acres, he called it. “This is the dead man’s room,” he’d say as he pointed out the front bedroom in a three-story frame in Brooklyn. “No way out.”

“This is where John Grant [his former aide] nearly got me fired. He lost the keys to the car and the Chief told me to take up [leave the scene]. Fifteen minutes later we’re still there looking at our shoes while he has someone bringing in another set of keys, and the Chief for the third time tells me, “Feehan, if you don’t get your sorry ass back in that car you’ll be sitting housewatch in the Bronx.” Bill would laugh as he remembered, “We get in the car and Grant says, `…all-in-all, I thought he was a little extreme.'”

He had a tale or two about his long-time second job, working security for the Helmsleys in their hotels around New York. He’d often be in the lobby when Mrs. Helmsley would breeze through and say in a commanding tone, “Feeny, take care of that.” Bill would do it, whatever it was. She never knew his name. He had the highest regard for her but could go on for hours about the characters that frequented the hotel bars during his overnight shift.

When new Commissioners arrived at the Fire Department Bill had to navigate his way through the sometimes turbulent waters of new experience. He put his ego aside and offered to make the transitions smooth. The Commissioners quickly came to realize they were dead in the water without him on their side.

He had dealt for Tommy Von Essen for years as a union delegate and then as union president and after assuming the Commissioner’s job for a few months, stepped aside gracefully when Mayor Giuliani appointed the brash Von Essen to the top spot. The Mayor’s one dictate, urged by outgoing Commissioner (later Police Commissioner) Howard Safir, was to keep Bill Feehan.

Feehan and Von Essen became fast friends, tackling problems that had never been addressed; fundamental issues of leadership, accountability and the critical push to increase firefighter safety. Keeping firefighters safe and well-trained was a passion for both of them and their resolve was firm.

A bit more firm than when it came to dealing with the men one on one.

They played good guy, bad guy when it came to discipline. Bill was famous for calling people in from the field for disciplinary action and having them cool their heels in the reception area for an hour or more while he and his executive officer, Henry McDonald, pumped each other up. They assured each other they were right, the guy didn’t deserve another chance, the difficult choice to let the offender go was the right thing to do and that they had to remain strong in their resolve. More often than not, the guy would come in and explain he had a sick wife at home, was working three jobs and promised he’d never, ever do it again. Bill would capitulate and there wouldn’t be a dry eye in the house. Henry McDonald always said that Bill knew more about what was in the minds of firefighters than they did. “There wasn’t a thought, a dream or a regret that he hadn’t had himself,” Chief McDonald said. “Even when they drove him crazy, he loved them to the core.”

As the Giuliani years drew to an end and retirement loomed on the horizon, the talk and nervous laughter turned to possible new careers. Bill practiced his concierge techniques in hopes of serving as a greeter at Home Depot. One of the great mysteries was how to get a MetroCard to take a bus or a subway after 20 years of having a Department car with lights and sirens.

On September 11, Bill is recorded on film doing what he did best. Being calm under fire, bringing order out of chaos, not without a little charm and humor. He is seen taking the elbow of a very frightened young lady in the lobby of tower number one and calmly pulling her close and walking her through just like it’s dinnertime in one of Mrs. Helmsley’s hotels. He smiles, takes her to safety and resumes command of the most horrific situation he’s ever been confronted with. He left the tower of One World Trade Center scouting a new command post for the Fire Department. He cleared everyone out of the Winter Garden at the World Financial Center, gave an evacuation order for those towers and proceeded to West Street where he joined Commissioner Tom Von Essen, Chief Pete Ganci and Chief Ray Downey to manage the horror unfolding before them. He winked at one of his Deputy Commissioners who didn’t want to believe what she saw and questioned him about how the incidents unfolded. Was it a mid-air collision? Could it have been an accident? He said with his usual Bill Feehan subtlety, “Are you a knucklehead? It’s terrorism.”

Then came the sickening roar, the realization that something was coming down, the dash for the garage and shelter. He worked his way through the darkness and out to the light. He sent everyone he saw north and he moved south to help those who were injured. He was with Chief Ganci and they did what they had promised to do on the day they were sworn in so many years ago; put themselves in harm’s way to help people in trouble. When the second tower came down, it came their way.

When the dust settled, and they knew he was gone, Bill’s Executive Chief Henry McDonald, his friend Ray Goldbach, John McLaughlin, and so many others clawed at the steel and concrete until they got him. Michael Regan, the young Deputy Commissioner who had learned at his feet and who would finish out his last few months with the Department in Bill’s job, helped to put him in the ambulance to bring him up to Bellevue. Later that night they brought his son Bill down to the site to show him where his Dad died.

On Saturday, September 16, in a light rain and cold wind, a crowd gathered at St. Mel’s in Queens to share their grief and shock and pay tribute to the Chief. To capture the essence of this man, father, grandfather, historian, mentor, leader, hero in the truest sense of the word, but above all a loving human being, was impossible in a eulogy. Maybe Bill himself said it best in words he wrote to remember another firefighter:

“The truest form of love is to lay down your life for another but the purest form of love is to cherish each other every day. Never leave a moment’s doubt that you love with your whole heart and soul. It’s a great legacy”

Bill Feehan left no doubt that he loved and was loved by all who knew him. ♦

_______________

Lynn Tierney worked with Chief Feehan as First Deputy Commissioner. She has since left the FDNY to work in the private sector. Tierney wrote the eulogies for many of the firefighters lost on September 11.

Leave a Reply