In his latest work, Irish artist Robert Ballagh explores the relationship between the Irish and the land.

℘℘℘

March 10, 2002, New York: Looking remarkably fresh after a long plane fide from Dublin, artist Robert Ballagh took time to show me around the recent exhibition of his new paintings that were displayed so beautifully at the Irish Arts Center for an exhibition entitled “Tír is Teanga” (Land and Language). The exhibition’s title relates to a nineteenth-century Irish cultural revival rallying call. In essence, the poetic emphasis links Ballagh’s current work to nineteenth century artistic and cultural concerns centering on land, politics and language which continue to prevail today.

Best known for his highly realistic figural works from the 1960s-70s, Ballagh’s current interest in landscape allows for a provocative exploration of his approach to his work. Upon reflection, these new paintings, like much of his previous work, reflect myriad nuances on political and cultural themes that are inextricably linked with Ireland, past and present.

“For most people, these works will represent a departure from what they traditionally expect from me. In my thirty-five years of painting and exhibiting, I never really dealt specifically with landscape before. Just two years ago, I decided to have a go at it after developing and working with new painting techniques that were used for the Riverdance designs.”

Typically, it takes up to six months for Ballagh to complete a painting. When Riverdance producer Moya Doherty, approached him to design the 50 to 60 visual images needed for the show, Ballagh quickly realized he needed to rethink his technical approach. He began working directly on the canvas without the use of glazes and under-painting he traditionally employed. “Specifically for the Riverdance production, when I began to think about landscape, I decided to develop the concept a bit more. As you can see, the paintings are quite fluid, I emphasized the looseness of the formal techniques, and decided to incorporate textural elements fight into the various compositions.”

Ballagh conveys a quiet sense of passionate detachment when discussing his work. He is equally delighted to reflect on his work’s art historical precedents, as he is to explain his concerns with formal approaches and techniques. This exhibition’s giclée prints are the result of a digital process, in which the original oil on canvas paintings are photographed, scanned and airbrushed. Using archival inks, Ballagh then printed the image directly onto watercolor paper.

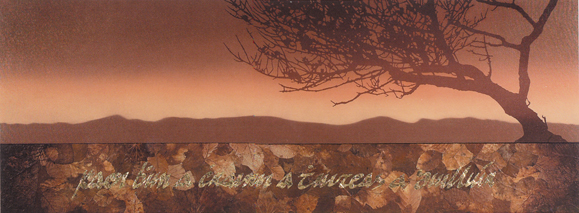

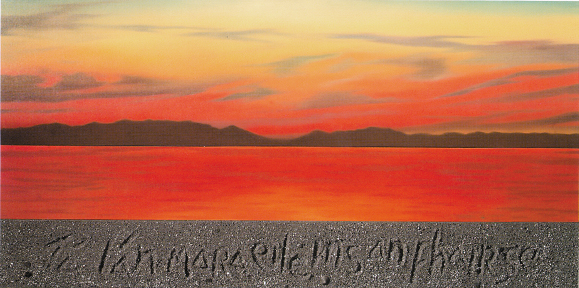

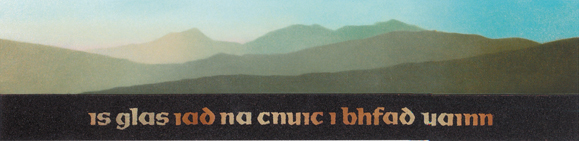

The three oil paintings in the exhibition – River Run (View of Dublin Bay), Fómhar (Autumn), and Réalt na Mara (Star of the Sea) – include actual textural, three-dimensional materials. In the prints, the sand, twigs and leaves are reproduced as photographs. This third section, or predella, incorporates the critical language component of the series with the enigmatic visual images.

Ballagh brilliantly contrasts and juxtaposes potent visual images of a mythic and romantic Ireland with the enduring, reaffirming power of the ancient Irish texts. By embracing the nuances and symbolic meanings of anonymous Irish proverbs, he decisively fuses political and cultural historic concerns with prevailing contemporary discourse.

Etched in glass, cast, bronzed or silver plated, the poignant titles include Dhéanfa sgéal de chlochaibh trágha (You would make a good story out of the stones of the strand), Faoi bhun an chrainn a thuiteas a dhuilliúr (It is at the foot of the tree the leaves fall), Tá lán mara eile ins an fharraige (There is another tide in the sea) and Rithid uisigí doimhne ciuín (Still waters run deep) The titles insist upon the enduring relevance and resonance of the power to name and indeed, own and inhabit Irish land.

Ballagh himself is no stranger to politics and for him, discussing the relationship between politics and the landscape provides an opportunity to reinvestigate themes, which didn’t particularly engage him in his younger years but now draw him in.

“I don’t know where the idea for incorporating the text came from, but very early on in the development of this series, it struck me to use the Irish language within my work. I reference Brian Friel’s brilliant play Translations, which refers to that early period in the nineteenth century when the whole country of Ireland was being surveyed.

“Essentially, the British changed the name of every street, mountain and body of water. Throwing out the Irish names, and in their place, enforcing the `Anglicized’ version (which may or may not have any relation to the actual meaning of the Irish name).

“These ideas have informed my work. I’m interested in reclaiming the Irish language, and in that process to reclaim part of Ireland’s history that existed long before the Anglicization.”

With reclamation in mind, Ballagh chose to depict panoramic, spectacular views of Irish land that primarily relates to myth, in opposition to a specific place within Ireland.

“There is a huge yearning for land in Ireland; in most other countries land was related to class, one group of people had it and the other didn’t. In those cases, it was a question of nationality. However, in Ireland the people had the land taken from their possession in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. It is extraordinary to think of a whole people and culture living in a society within a country without owning any of the land.

“One of the things I wanted to try and get across is the mystical thing; it is not a specific place. If I gave it a specific location, I feel it loses the mythic quality I’m interested in representing.”

Questioned about his insistence on the formal union between text and the visual, Ballagh explained his feelings towards the issue of accessibility in contemporary art. “If you are accustomed to an Irish landscape painting being a beautiful image from the past, that approach isn’t really all that modern. I hope this new work is challenging to people. I’m concerned that a lot of contemporary art puts an insurmountable barrier to an audience and I feel strongly that it’s necessary to create an `open door’ to let people in. I don’t think great art should be facile, but I don’t think it should be so complex that it is inaccessible. I feel a good artist can make complex art that is open and can appeal to many levels of appreciation. Not everyone has had time to study art history. I think the work should be sufficiently sophisticated to give many levels of meaning.”

For some Americans, understanding the unique significance of the depiction of Irish landscape may require a deeper, more thoughtful look at the longstanding and often torturous connection that exists in Ireland between land, history, language and politics. “History is written about events and people, but in Ireland an underlying factor is always the land. For so many centuries, the Irish were a landless people, and we are deeply affected by our desire to own it [land] as it was.”

Post-millennium, many Irish artists, including Ballagh, explore the issues of Ireland and its visual representation. This intangible connection between Irish identity and visual representation attracts visual artists who probe, expose and deconstruct preconceived notions of what land means for the Irish, then and now. Ballagh’s recent work in particular invites the viewer to rethink the significance of Irish landscape. Tír is Teanga is rife with implicit and explicit allusions to politics, power and history. Ballagh’s reclamation of his cultural and artistic roots reveals a depth of feelings beneath his cool, detached formalist approach. “That is what was driving me in this work, to bring the true Irish back to the land scape…I’m interested in playing games between text and image. Text relates to the visual, but of course it has a deeper meaning on a human level.” ♦

Leave a Reply