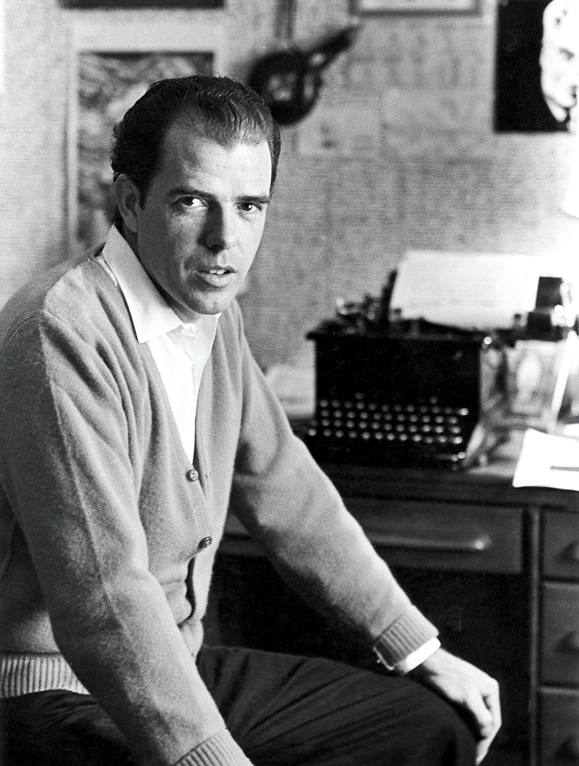

William Kennedy, known as the author who captured Albany, New York, talks to Tom Deignan.

℘℘℘

William Kennedy is telling a story about his father that could very well be a haunting moment from any one of his seven “Albany cycle” novels.

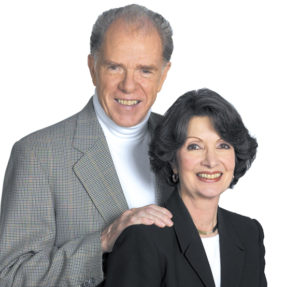

“My father’s father came from Tipperary,” the novelist, 74, says over an Irish breakfast in Fitzpatrick’s mid-town Manhattan hotel. Kennedy’s radiant wife, Dana, a onetime model and Broadway performer to whom Kenndey proposed after three dates in 1957, is seated to his right.

“Dad was on the edge of senility at this point,” Kennedy continues, “and he’s telling this story. And he just starts speaking in a brogue. And, I mean, it was a terrific brogue…I’m sure his father spoke like that.”

There are such moments, when the past collides with the present, when ghosts seem to converse with the living, in all of Kennedy’s books, including his latest, Roscoe. At one point, Kennedy’s titular, Falstaffian hero is staring at his dead best friend, who promptly rises from the chair, walks to the bathroom and begins shaving.

“Who gave you the OK to die?” Roscoe asks.

A few weeks after Roscoe was lauded on the front page of The New York Times Book Review, Kennedy himself reviewed Joe Klein’s book The Natural: The Misunderstood Presidency of Bill Clinton for the Review.

It seemed a slightly odd assignment for a writer who is to Albany what Joyce is to Dublin, what Philip Roth is to Newark, and what Dickens is to London. Kennedy, mind you, is a man of tremendous intellect. Friends say he’ll lecture on Faulkner and Fitzgerald one minute, then sing Irish songs and Sinatra the next.

Still, why Kennedy on Bill Clinton?

Well, blame Ireland – and Roscoe.

Kennedy was one of 40 Irish Americans who ventured over to Ireland in 1995 with the president, during some of the more tense hours of the peace process. Kennedy, in fact, is a regular visitor to Ireland, where all of his six Albany books will be re-released, along with Roscoe, later this year.

Roscoe is indeed a deeply political book, easily one of the best American political novels written in decades, perhaps since Edwin O’Connor’s The Last Hurrah.

Sure, loyal Irish Democrats play a large role in previous Kennedy works, including Legs (1975) and perhaps his most celebrated novel, Ironweed (1983).

But those books focused, respectively, on a romantic Irish gangster and an alcoholic hobo. The main characters in Roscoe are wealthy, educated and powerful insiders. Which doesn’t necessarily make them respectable.

“Honesty is the best policy for people striving to be poor,” according to Roscoe Conway, the lawyer with a broken heart and poet’s soul. Warned in a dream that “ignorance of the moral law is no excuse [for wrongdoing],” Roscoe replies, “No, but it’s a living.”

Roscoe, however, is not some lovable scoundrel, or a political Robin Hood stealing from the rich to benefit the Irish working classes of Albany. Instead, Roscoe’s quips are rooted in fierce, finely-honed survival instincts. In a brilliant digression, Roscoe recalls learning that “fraudulence [is] a golden tool” from the Christian Brothers. After acing a test, young Roscoe stands accused of cheating. After intentionally performing “sufficient[ly] to pass but not excel” on a follow-up, he is declared “normal — wholesomely mediocre. We won’t prosecute him for sinful superiority.”

This passage could cut too close to the bone for some Irish Catholics. But then again, Kennedy has never been one to shy away from the dark side of the Irish urban experience. As he wrote in Billy Phelan’s Greatest Game: “The Irish always wrote good letters. If they could write.”

This time around, Kennedy offers readers a fresh look at Irish political machines, those often-loved, often-loathed operations which ran cities from the time of the Famine right up until, at least in the case of Kennedy’s Albany, the 21 st century.

Kennedy likes to point out that one mayor elected by Dan O’Connell’s legendary machine, which took over Albany in 1921, held office for over four decades, longer than monarchs or despots such as Napoleon, Henry VIII or Stalin ever held power.

Roscoe is Kennedy’s ode to Albany politics — five years in the writing, some five decades or so in the research. The reviews have been uniformly glittering.

“Roscoe is the most successful book I’ve ever written,” Kennedy declares, clearly a bit surprised himself. “I thought Ironweed was a success,” he adds, of the book later turned into a Meryl Streep/Jack Nicholson movie. “But everybody seems to be reviewing [Roscoe]. Even The Economist. It’s a great time now. I’m very happy.”

Down-to-earth and humble, freely admitting he has no idea what “Irish pudding” is (he likes it when he tastes it), Kennedy enjoys his success unabashedly. And why not? To say the least, it’s been a long time in the making.

Born in Irish North Albany in 1928, Kennedy was an only child, whose father was a deputy sheriff. On the county payroll, Kennedy’s Dad knew a thing or two about what his novelist son calls, simply, “the machine.”

As with so many Irish American novelists, journalism initially beckoned Kennedy, who graduated from Siena College in 1949, and did a stint in the Army during the Korean War.

“There were no writers in my family. I don’t know where I came out of,” says Kennedy, before mischievously declaring, “I was hatched in a peculiar way.”

Initially, Kennedy worked as a reporter at the Albany Times Union and a sportswriter at the Glens Falls Post-Star.

“My parents liked the idea of my name being in the paper [but] ultimately, they didn’t really give a damn [what I did for a living]. But they were always supportive.”

It’s interesting to note that the writer who, in time, would come to be known as the “Bard of Albany” eventually felt cramped in his native burg, a place of old men and corrupt politics, in his mind. (He even registered to vote as — gasp! — an independent.)

So, Kennedy took a job with an English-language newspaper in Puerto Rico. One night at a party he met a stunning brunette whom, to this day, he calls his “Latin from Manhattan.”

Dana Sosa, as she was known then, was a showgirl, who earned rave reviews for her performance in New Faces of 1956 on Broadway. Kennedy asked Dana out on a New Year’s Eve date, but she had to be with family when the clock struck midnight.

“I did say I’d meet him afterwards,” she recalled.

Four weeks later, Dana and William embarked on a marriage which would see its share of tough financial times, as Kennedy wrestled with the daily demands of journalism and the quiet time desperately needed to write fiction. Kennedy did manage to take a creative writing class at the University of Puerto Rico, taught by a visiting professor (and future Nobel Prize winner) named Saul Bellow.

Dana, meanwhile, modeled and danced to bring in much-needed cash. In the early 1960s, with Kennedy’s father ailing, the Albany expat returned home, buying a house in nearby Averill Park.

For the Puerto Rican girl from Manhattan, the move was, to say the least, a shock.

“I didn’t leave the house for months,” she admits.

While the city girl slowly grew accustomed to things like open spaces, trees and fresh air, the native son, who once craved escape, rediscovered Albany.

This process took on grand proportions when Kennedy was asked to write (a 26-part series) about Albany neighborhoods for the Times-Union.

The people and politics that once seemed too provincial and unseemly to Kennedy, suddenly seemed the stuff of poetry.

“It also explained my own history to me, my family’s own involvement. It was so pervasive — so many people in a given family were involved in the machine in one way or another.”

He was now able to take a more complex view of local politics.

“Obviously, in a certain way they were scalawags. But they had to be more than that…they were delivering in a certain way that was significant for [voters]. Just plunder would not solve the [voters’] problems.”

The lofty praise heaped upon Roscoe may have been a surprise for a political novel, but it is not the first time William Kennedy defied publishing conventions, only to be rewarded handsomely for it. Ironweed, for example, was turned down by over a dozen publishing houses. Who, editor after editor asked, wants to read about a depressing Irish hobo, who once played baseball and now spends his days drinking and communing with the dead when other hoboes are not around?

Who? Saul Bellow, that’s who.

Legs and Billy Phelan’s Greatest Game, Kennedy’s first two Albany books, had been published to solid reviews but paltry sales. It was a critical moment for Kennedy and Dana, who by this time had two daughters, Dana and Kathy, and a younger son, Brendan. Kennedy had done some teaching, and was also taking journalism assignments. Esquire magazine was among those who came calling, in search of an interview with an old teacher of Kennedy’s.

It turns out Saul Bellow was a fan of Kennedy’s first two Albany books, as well as Ironweed, after he read it. In a letter of recommendation that would seem the stuff of any struggling novelist’s fantasy, Bellow wrote to Viking urging them to publish Ironweed, calling Kennedy’s Albany works “memorable, a distinguished group of books.”

Suddenly, everyone saw great things in Kennedy’s fiction. Ironweed won the Pulitzer Prize and National Book Critics Circle Award. Kennedy also got a phone call in 1983 from the good folks who run the MacArthur Foundation. Kennedy was awarded a “genius grant” of over $250,000 over five years. He used the money to start the New York State Writers Institute. Movie director Francis Ford Coppola also came calling, looking for help with his jazz age epic, The Cotton Club.

Nearly two decades later, William and Dana Kennedy once again find themselves riding high. There’s talk of a Roscoe movie deal, and Kennedy has been working on a Legs screenplay with director/actor/writer Ed Bums, who has been trying to get Legs to the big screen for a number of years.

On this day, after attending Irish America’s annual March bash at the Plaza Hotel in Manhattan the night before, Dana and William are at the tail end of a whirlwind publicity tour, which has already taken them up and down the West Coast and from Boston to Washington, D.C.

Some grumpy authors may complain about the rigors of the book tour. Not these two.

“I love it. We have a really good time when we go out on the road,” Dana says. “Everyplace we go is a party.” She says this with a bit of a laugh, but you have no problem believing her. In fact, she makes you want to be wherever they are going next.

Perhaps it is precisely because Kennedy had earned so many accolades previously that the success of Roscoe is a bit surprising, even to the author. What more, after all, could there be to say about Albany and its people?

In Kennedy’s mind, he’d never taken on “the machine.” By his estimate, he’d had 50 years’ worth of interviews, notes and memories. But translating that into compelling fiction seemed a daunting task.

“You can’t predict how it will be received…it’s a political novel, you can’t be sure. You work five years on a thing, you assume it’s a stellar piece of work, at least that’s what you tell yourself when you write.”

One of the most impressive things about Roscoe is the amount of plot and history Kennedy packs into less than 300 pages.

“I thought it was going to be a longer book,” Kennedy admits. When it’s noted that many authors have stretched such material into 800-page tomes, Kennedy laughs.

“I’m basically a newspaperman still. I don’t want to write [800-page novels] and I don’t want to read them.”

Roscoe opens in 1945. The revelry of V-J Day overshadows the harsh fact that New York’s Republican governor is once again charging Albany’s Democrats with corruption.

Chieftain Roscoe – the son of a three-time Mayor, who chose never to run for office himself– proclaims he’s done with politics, “sick of carrying time around on my back like a bundle of rocks.”

Kennedy says: “It took me a while to figure out how to tell the story. I had started trying to tell it from the view of the political boss…but I needed a smarter more articulate character. I had to have someone who’d be active in all the realms of the story. So I decided to make [Roscoe] a lawyer and give him a history of his own.”

Roscoe’s heart, we learn, was broken when the love of his life, Veronica, married a better-bred political pal, Elisha. Roscoe then married Veronica’s sister, to disastrous results. After Elisha hears Roscoe’s retirement plans, he again one-ups his friend: he commits suicide. Denied his last hurrah, Roscoe’s political instincts kick in. They are nearly as strong as his conflicted emotions: the love of his life, after all, is now a widow.

Veronica, meanwhile, has been dragged into a salacious lawsuit involving a family inheritance and her never-officially-adopted son. Kennedy delights in ratcheting up the spicy plot twists, throwing even a dashing Russian prince into the mix. Only Roscoe’s maneuverings– in court, in brothels and in the backrooms of bars– can win the day for Veronica.

For all this insider backstabbing, however, it’s important that Roscoe not be seen solely as Kennedy’s great book on politics. In one scene, which initially seems merely a colorful detour, Roscoe attends a cockfight. Quickly, it becomes clear what a powerful metaphor Kennedy has– for human nature as well as politics. That Kennedy also hangs a tragic plot line on such an absurd thing as a fixed cockfight is a testament to his achievement.

So, were the machines ultimately good or bad for the Irish?

“The machines were a way these inarticulate masses were able to find a place in this society, and a very significant one. They existed in a great many cities…the Irish had a way into the center of the world which they hadn’t had.”

To Kennedy, it was also a way to ensure they held their fate in their own hands.

“I think there was a political savvy that had to come natural to these people. They didn’t want to go back to the land. They became urban as a new way of life, they wouldn’t trust the land after the famine. It makes sense. I’m sure there are a lot of Irish farmers who disagree.”

Kennedy says his own youth was only marginally Irish.

“We sang Irish songs on St. Patrick’s Day. You’d wear a green tie, but that’s it.”

His Dad, however, did get over there on leave during World War I. Kennedy also went while in the military, unaware that he had relatives there.

“I had a neighbor, I was tracking down his family. In the process I found I did have family. A cousin wrote me a letter about another cousin in Tipperary. It was great.”

Last year, Kennedy attended a writers’ conference in Galway with Frank McCourt and others, and is looking forward to returning when his books are released there.

It’s anybody’s guess, of course, what the Irish will make of Roscoe, who vows to tell the truth when he can, and who learned to vote the dead from his Dad. (“Just because they’re dead don’t mean they’re Republicans.”)

But if they’re sick and tired of lying politicians like this, Irish or otherwise, well, as the last words of his book attest, don’t blame Kennedy.

“Blame Roscoe.” ♦

Leave a Reply