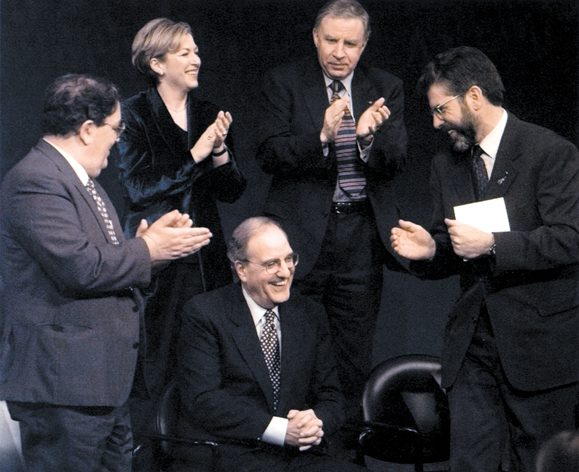

CAUTION IS ADVISED WHEN MAKING COMPARISONS BETWEEN AREAS AS COMPLICATED AND DIVERGENT AS NORTHERN IRELAND AND THE MIDDLE EAST. BUT AS THE VIOLENCE IN THE MIDDLE EAST INTENSIFIED, DIPLOMATS AND PEACE-MAKERS STRAIN TO FIND A WAY FORWARD BY EXAMINING THE DYNAMICS THAT SOLIDIFIED NEW POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS IN NORTHERN IRELAND AND BROUGHT A PEACEFUL SOLUTION TO A PROBLEM THAT THE “EXPERTS” SAID COULD NEVER BE RESOLVED. SENATOR GEORGE MITCHELL’S INVOLVEMENT IN NORTHERN IRELAND IS WELL DOCUMENTED. AFTER HE RETIRED FROM THE UNITED STATES SENATE IN 1995, THEN PRESIDENT BILL CLINTON ASKED HIM TO LEAD AN INITIATIVE ON TRADE AND INVESTMENT IN NORTHERN IRELAND. HE WAS THEN APPOINTED BY THE BRITISH AND IRISH GOVERNMENTS TO CHAIR AN INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION ON DISARMAMENT OF PARAMILITARY WEAPONS, A PRECURSOR TO THE NEGOTIATIONS THAT HE CHAIRED, WHICH LED TO THE 1998 GOOD FRIDAY AGREEMENT.

WHEN CLINTON WAS LOOKING FOR A WAY TO BREAK THE IMPASSE IN THE MIDDLE EAST, HE AGAIN TURNED TO MITCHELL. THE FORMER SENATOR CHAIRED A FACT-FINDING COMMITTEE THAT EVENTUALLY DREW UP A SERIES OF RECOMMENDATIONS FOR MOVING TOWARDS A NEGOTIATED SETTLEMENT OF THE ESCALATING CONFLICT. THE “MITCHELL REPORT” WAS DELIVERED TO PRESIDENT GEORGE BUSH IN APRIL OF 2001. TWO PRIMARY COMPONENTS OF THE REPORT WERE THE DEMAND THAT THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY, LED BY YASSER ARAFAT, MAKE A “100 PERCENT EFFORT” TO PREVENT TERRORIST OPERATIONS AND THAT THE ISRAELI GOVERNMENT FREEZE ALL SETTLEMENT ACTIVITY. KELLY CANDAELE TALKED TO FORMER SENATOR MITCHELL IN FEBRUARY, 2002.

Kelly Candaele: Reflect on your experience in Northern Ireland. Were there lessons that you learned there or a paradigm that helped formulate your thinking as you went to the Middle East?

Senator Mitchell: There are some obvious similarities. But as much as we would like it to be, there is no formula that once applied in one situation can simply be transferred to another situation. The differences are significant, the personalities are different, the histories are different, and though there are certain principles that may apply in any peace negotiation process, I think that one must be cautious about transposing elements from one place to another.

What are those principles that apply in both cases?

First there has to be a great deal of patience and perseverance. It’s easy to become discouraged. I’m asked by reporters almost every day since there is continually violence in the Middle East, how can there ever be an agreement? Since one party says no to this, how can you ever expect them to say yes? The fact is, all of these situations are difficult, complex, have deep historic roots, and require an almost endless supply of patience and perseverance and determination.

Second, in the pursuit of peace, one cannot be deterred by those who use violence to achieve a political objective. In Northern Ireland when I started the process, I was told repeatedly by the delegates that we had to keep it going because if it ended the conflict would resume. Over the two years of negotiations and during the second round of negotiations I presided over, there were repeated acts of violence that had the obvious intention of derailing the process. But we kept it going.

And I think the same is proving to be true in the Middle East. The process has to keep going even in the face of horrific violence and in the face of setback after setback.

The third principle is that it takes strong and courageous leadership in the face of violence, in the face of high emotion and demands for retaliation, to take risks for peace.

And fourth, which I think is now at work in the Middle East, there is no such thing as a conflict that cannot be ended. All conflicts are created and sustained by human beings. There will come a time when the cost of conflict is so high that people will turn to the alternative of negotiation and discussion even though that entails painful and difficult political risks for them.

I believe there was a peace agreement in Northern Ireland because people were sick of war. The conflict raged on for a quarter of a century and the overwhelming number of people in Northern Ireland were sick of the war. I think that’s going to happen in the Middle East. Life has become unbearable for the members of both societies. Indeed that’s precisely what Prime Minister Sharon and Chairman Arafat both told me in my last meetings with them months ago. “Life has become unbearable for our people,” is what they said. So I think they will mm back to negotiation because as painful as it is, it’s less difficult and less costly than conflict.

I was struck by the similarity in language of the Mitchell Report on the Middle East and the language that took place in Northern Ireland. It seems there are certain structural similarities to peace-making in both places. But differences as well. It seems clear that in Northern Ireland, to a great extent, the parties had come to terms with their own problems and could meet at a negotiation table. There are those who say that that dynamic has not happened yet in the Middle East That the Palestinians have not come to terms with the reality of Israel’s existence. And that Arafat is not Gerry Adams in that he has not been able to tell his followers the truth about that situation.

Well, the public opinion polls consistently show that a majority in both societies — Israeli and Palestinian — support a peaceful resolution that will result in two states. Certainly, all of the negotiations and agreements, and most specifically the Oslo Accord, explicitly acknowledged the two-state solution. So it’s quite clear that there was an acceptance of that in both societies. It is of course true that there are some Palestinians who reject that, and who take the position that there cannot be a Jewish state in the Middle East. That position is wrong and it is a fantasy. That position is not going to be a reality. On the other side there are some in Israel who favor a solution called “transference,” and believe that somehow the three-and-a-half million Palestinians will be removed to another place. That policy is a fantasy and will not become a reality. But I think it’s clear, certainly to me, that history, geography, destiny has created a situation where they must live side-by-side in separate states. The question is how to reach an agreement to permit that to occur in a manner that’s peaceful and brings prosperity for both.

When there was a resurgence of IRA violence after the 1994 cease-fire, there were some who said “Gerry Adams is irrelevant and we are not negotiating with a guy who can’t deliver.” Sharon has said that about Arafat.

That’s stretching for analogies that don’t exist. There are a couple of principles that I think are applicable here. By the time I got to Northern Ireland in early 1995 it had become clear there was a military stalemate. The IRA could not succeed in its stated objective of expelling Britain from Northern Ireland through the use of force. And Britain, certainly not while retaining its democratic values, could not wipe-out the IRA, as some of the more aggressive urged at the time. So there was a military stalemate. Although the military circumstances are quite different in the Middle East the overall situation is similar in that there is no military solution to this problem. Israel has overwhelming military superiority but it is of course very difficult to bring it to bear in an effective manner. It simply isn’t possible to impose a military solution because the resistance would simply continue. On the Palestinian side, it is simply not going to happen, that the state of Israel is going to be destroyed.

There is a strong sense, because Israel withdrew from Lebanon, that violence does achieve something. The IRA believed for a long time that the only effective approach to the British was the bomb and the bullet.

Let’s be realistic. The notion that political objectives can be achieved by violence didn’t originate in, nor is it limited to, Northern Ireland or the Middle East. It’s as old as mankind and for Americans the prime example is our own Revolutionary War. So the question is, what is the circumstance under which it occurs? I think it’s impossible to generalize in these situations. And it is even impossible to have an unwavering, never-changing policy. A policy that is correct today may be incorrect tomorrow because the circumstances change. At least in both Northern Ireland and the Middle East there is no feasible military solution. Neither side can with confidence pursue a solution that is entirely military in nature and doesn’t contemplate some kind of negotiation to try and achieve accommodation of political objectives. That I think is the greatest similarity.

Now, that doesn’t apply in every situation. I’ve been asked why doesn’t the United States negotiate with bin Laden and Afghanistan and Al Qaeda? And of course there is no basis for negotiation there. There is no specific delineated political objective on which a negotiation could be based. There is no credible entity or person with whom to negotiate. I point that out merely to say that each situation is different and unique and each one must be addressed in the circumstances at the time.

In terms of Arafat, his role as the sole elected authority of the Palestinian people presumes an ability to control violence.

The fact is he doesn’t have complete control and everybody knows that. In our committee’s report we called upon Arafat to make a one hundred percent effort to control violence. Israeli government officials suggested that language to us. They said, “We know he doesn’t have complete control but he needs to make a complete effort, which he has not done.”

In terms of the critical issues of security for Israel and the dismantling of settlements which is central to the Palestinians, many would say there has not been a great deal of change [since the Oslo Accords] and in fact things have gotten worse.

[After Oslo] there was a substantial period of cooperation and very effective security coordination, which is the one thing that both sides agreed on in their meetings with us. There was a sharp reduction in violence. There was the belief that there was an agreement to have separate states, that there would be a viable, geographically contiguous, independent Palestinian state. That has come to be recognized and accepted much more widely than before. The problem arose in that the hoped-for economic improvement did not occur. Unemployment was higher at the end of the Oslo period than at the beginning. Economic growth and prosperity did not materialize. In what Clinton said, he was right: that you need economic growth and job creation to underpin these very difficult transitions. That’s what’s necessary in the Middle East now. There’s been a devastating loss to the economy on both sides but greater to the Palestinians as a result of this conflict. ♦

Leave a Reply