Love, courage and the kindness of strangers.

And now, memory crashes all of 2001 into the 100 minutes between 8:48 and 10:28 of that morning in September.

When the clock ran out and the losses were counted, the lists of the missing turned out to be rich with Kevins and Brians, Patricks and Moiras, Seans and Anns. Among the 2,874 names of those lost at the World Trade Center, some one in five showed traces of Irish ancestry, at least by one purely subjective inspection.

If you could freeze just about any instant in those 100 minutes, you might glimpse the full biography of an American immigrant tribe: the children of a tiny island in the North Atlantic, their grandsons and granddaughters, on the move.

No one was surprised to see so many Irish names among the lost rescue workers. The revelation, to many, was the throng of Irish-Americans who had taken up work in the financial industries based at the World Trade Center.

Coming out of parochial schools, they had found a modern prairie where opportunity lay not on the vast western horizon, but straight up, in vertical space, behind a trader’s desk, in an insurance company, or practicing law.

For entry to so many of these jobs, plain moxie served as well as paper credentials from pricey colleges.

“In the towers, you had two strands of Irish-Americans — the firefighters on the way up and the Wall Street people,” said David Hunt, a restaurant owner and native of Inwood in northern Manhattan. “They met in the stairways.”

As did many, many others. The people lost on September 11th made for a vast assembly of humanity. To note the prevalence of Irish names is to see, as well, the faces of a great city: the Dominican security guards who never left their $10.51 an hour posts; the early-to-rise Ecuadorian busboys at Windows on the World; Abe Zelmanowitz, Orthodox Jew of Brooklyn, who would not abandon his quadriplegic Christian friend, Edward Beyea, in his wheelchair on the 27th floor. The franchise on loss is held by no single race, homeland or religion. September 11, 2001 created an empire of the stricken.

On one level, much of what happened inside the towers on that morning is a mystery. There was little mixing between those who lived and those who did not. Few escaped. The precise physics of what happened in the final minutes is now a fragile puzzle of inferences drawn from last sightings and final words. Yet it is also plain now, nearly six months distant from the awful velocity of that day, that so many people remained steady, sure of themselves, not only counting the moments but making the moment count.

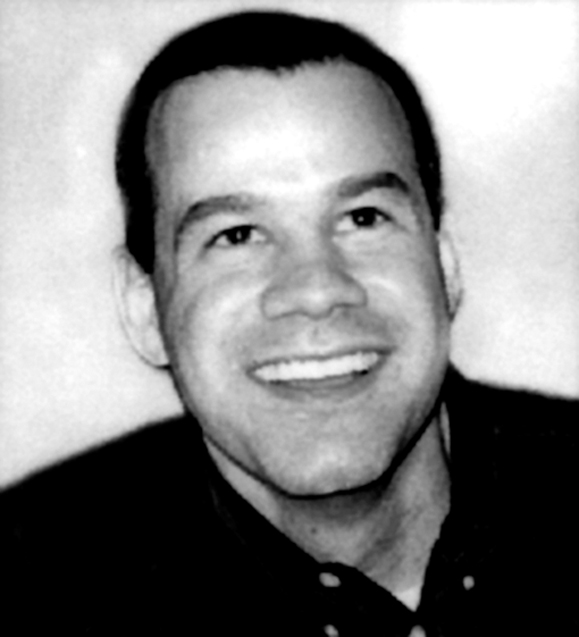

So in the tower stairs, you might have run across Damian Meehan, the youngest son in a clan of nine children raised in Inwood by Michael and Margaret Meehan of Donegal. Two of the Meehan sons are firefighters; another is a detective. Damian had come along when opportunities were clear and open on Wall Street. A spider net of Inwood guys had formed around the commodities exchange, with each new arrival reaching back to the old neighborhood to bring along another relative, another sharp friend. His brother-in-law, Marty Boyle, had set him up with his first job, and Damian was happy to work among people he knew from Inwood and from Gaelic football. At home in Glen Rock, N.J., he had a happy marriage to Joann McCarthy, and they had a young son named Damian Jr., and another one on the way.

An excellent athlete and runner, Damian Meehan worked for Carr Futures on the 92nd floor of One World Trade Center. That was within the impact area of the first attacking airplane. No one from that floor lived, though quite a few survived the initial crash. In the minutes immediately afterward, Damian Meehan spoke to one of his firefighting brothers for advice.

Some in the Meehan family believe Damian would have tried to lead others out, and indeed, his body was found with a group of 25 civilians and firefighters, making it at least plausible that he had gotten well below the 92nd floor when the building collapsed. To the firefighting Meehans, this meant their little brother had spent his last minutes in the company of people they regarded as family. “I’m glad he was with the brothers,” Kevin Meehan said. “Probably helping.”

You might have also encountered Bruce Reynolds, last seen at the Trade Center attending to a woman burned by a spill of flaming jet fuel. A police officer for the Port Authority, he was normally assigned to the George Washington Bridge Bus Terminal.

Raised in Inwood like Damian Meehan, Bruce had been one of the first African-American children to grow up in that neighborhood. His family had made its mark by reclaiming scrub land along Park Terrace and turning it into a vibrant community garden, where Bruce rose along with the flowers and trees that he, his father and his mother had planted. He married Marian McBride, from Donegal, and joined the Ancient Order of Hibernians chapter in Hudson County, N.J.

They moved to Knowlton, N.J., near the Delaware Water Gap, to give their children the country life. At a memorial service, Bruce’s father, J.A. Reynolds, spoke of the quest for “life everlasting.” He remembered collecting oak leaves when Bruce was a boy, and bringing them home to compare to the skin tones of his mother and father, tracking the run of beauty across the color spectrum. When the mountains of western New Jersey take their autumn colors, Mr. Reynolds said, they should think of Bruce, the lost son and father and husband, and find him again, in the beauty of those colors.

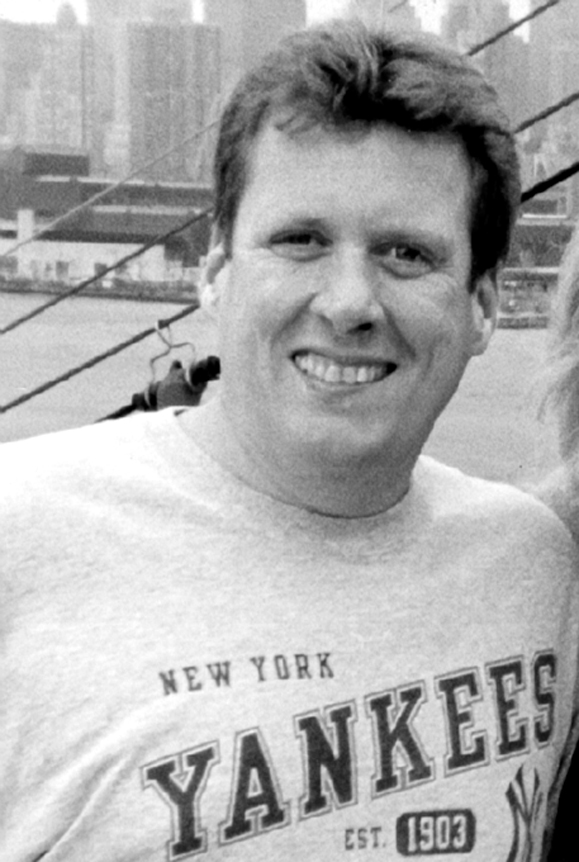

Or you might have run into Luke Nee. Straight out of Cardinal Hayes High School, he spotted an ad in the Daily News.

A company setting up shop on Wall Street was looking for people with an aptitude for arithmetic. Luke strolled into Drexel Burnham Lambert, and soon five buddies from his block — Minerva Place, just off the Grand Concourse — joined him.

“He’d say, `It’s a small world, but I wouldn’t want to paint it,'” said his brother, John Nee.

The son of immigrants from the west of Ireland, Luke locked onto the simple pleasures with his wife, Irene Lavelle, and their son, Patrick. A day at Jones Beach. A Friday night at Yankee Stadium. A couple of novels for the train ride in from Stony Point. Meatball heroes on a Saturday night, a rented video, an evening in front of the TV with Patrick and Irene. When Drexel Burnham shut down, his skills were in demand at another rising financial concern, Cantor Fitzgerald. So on the morning of September 11, 2001 — as it should happen, the 19th anniversary of the wedding day of Irene and Luke — off he went to work at the World Trade Center. And then men sick with religion or politics or hate seized the planes and changed the world.

Or so they thought.

From the doomed north tower, Luke Nee made a final call to Irene, to make sure that Patrick knew that his Dad loved him, and to tell her again what he had told her 19 years earlier.

Luke Nee, Bruce Reynolds, Damian Meehan, and nearly 3,000 others had left their homes on September 11 in the usual sprint for work. They spent their final minutes fighting for life. Some helped weak friends and burned strangers down stairs, across acres of burning debris, or huddled with them in the failing towers. Others made phone calls, wrote e-mails, sent pages. With their last minutes, they sent word to the people they loved that they loved them still. And when they were gone, we could look back and see how they lived out that 100-minute year, filling it with struggle, honor, and love, all of it packed into a single blink of eternity. ♦

Leave a Reply